![]()

POPULATION

At least 800,000 people, about 10 per cent of the population, died from hunger and disease between 1845 and 1851. But there was nothing unique, by the standards of pre-industrial subsistence crises, about the famine. The death rate had been frequently equalled in earlier European famines, including, possibly, in Ireland itself during 1740–41. Despite death and emigration the population in 1851, 6·6 million, was still among the highest ever recorded. Population had, moreover, usually recovered rapidly from earlier famines. But, far from recovering after 1851, it fell to 4·4 million by 1911. What was peculiar, therefore, was not the famine, but the long-term response of Irish society to this short-term calamity.

Six main factors influenced post-famine demographic development: the changing rural class structure, rising age at marriage, declining marriage and birth rates, a static death rate and emigration. The combination of these six factors was unique to Ireland, but they did not combine within the country in precisely the same manner from decade to decade or from province to province, resulting, as can be seen from the following table, in marked regional fluctuations in the pace of population decline.

Rate of Population Decline (%)

| | Leinster | Munster | Ulster | Connacht | Ireland |

| 1841–51 | 15·3 | 22·5 | 15·7 | 28·8 | 19·9 |

| 1851–61 | 12·9 | 18·5 | 4·8 | 9·6 | 11·5 |

| 1861–71 | 8·1 | 7·9 | 4·2 | 7·3 | 6·7 |

| 1871–81 | 4·5 | 4·5 | 4·9 | 2·9 | 4·4 |

| 1881–91 | 7·1 | 11·9 | 7·1 | 11·8 | 9·1 |

| 1891–1901 | 3·3 | 8·3 | 2·3 | 10.1 | 5·2 |

| 1901–11 | +0·8 | 3·8 | 0·1 | 5·6 | 1·5 |

| 1841–1911 | 41·2 | 56·8 | 33·8 | 57·0 | 46·4 |

The enumeration of many farmers’ children as labourers in the census of 1841 complicates calculation of the precise number of landless labourers, but even a rough estimate shows that the famine initiated a transformation in rural social structure.

| | Labourers | Cottiers (under 5 acres) | Farmers (5–15 acres) | (over 15 acres) |

| 1845 | 700,000 | 300,000 | 310,000 | 277,000 |

| 1851 | 500,000 | 88,000 | 192,000 | 290,000 |

| 1910 | 300,000 | 62,000 | 154,000 | 304,000 |

Between 1845 and 1851 the number of labourers and cottiers fell 40 per cent, the number of farmers 20 per cent. During the following 60 years the number of labourers and cottiers again fell about 40 per cent, the number of farmers only 5 per cent. Within the rural community the class balance swung sharply in favour of farmers, and within the farming community it swung even more sharply in favour of bigger and against smaller farmers.

These striking shifts in rural social structure may help explain one of the most intractable problems to perplex students of nineteenth-century Ireland, the apparently abrupt reversal of demographic direction involved in converting the Irish from one of the earliest marrying to the latest and most rarely marrying people in Europe. Between 1845 and 1914 average male age at marriage rose from about 25 to 33, average female age from about 21 to 28. The decline in crude marriage rate (the number of marriages per 1,000 of the population) from about 7 in the immediate pre-famine period to about 5 by 1880, and the increase in the proportion of females in the age group 45–54 never married, from 12 per cent in 1851 to 26 per cent in 1911, distinguished Ireland as a demographic freak.

Such striking changes appear to indicate an entirely new mentality among the survivors of the holocaust, to represent a sharp reversal of existing patterns of behaviour. The change has been widely associated with the switch from sub-division of land among all sons to inheritance by only one child. According to this interpretation, land was subordinated to people before the famine: henceforth people were subordinated to land. Sub-division meant inheritance for all sons, young marriages, large families. Consolidation condemned the younger children to the emigrant ship or the shelf. For the inheritor it entailed postponing marriage until the parental farm became available. This interpretation, though partially valid, greatly exaggerates the scale and speed of the transformation. Age at marriage in pre-famine Ireland probably varied more or less directly with the value of the farm. Within any given region, labourers and cottiers married earlier than small farmers, who in turn married earlier than larger farmers. Sub-division was largely confined, for a generation before the famine, to already small farms in the far west. In the rest of the country even small farmers generally insisted on a dowry from the daughter-in-law and rarely subdivided. A disproportionate number of famine survivors belonged to classes with above average age at marriage, already unaccustomed to sub-divide. Even had age at marriage remained unchanged within social groups, the reduction in the proportion of earlier marrying strata would have raised average age at marriage. The sizes of strata changed more than their behaviour. Age at marriage within groups gradually increased, but the overall change did not require the whole peasantry to revolutionise their attitude under the cathartic impact of the tragedy, but rather required the surviving labourers and cottiers, who previously had little to lose from early marriage, to adopt the existing attitudes of more prudent calculators. However much these attitudes hardened and sharpened in the congenial post-famine circumstances, they were inherited rather than created by post-famine man.

As the rungs on the social ladder widened, as the cottier disappeared and the average size of farm increased, it became increasingly difficult to marry a little above or a little beneath oneself. The range of social choice for bidders in the marriage market narrowed. Mixed marriages, between farmers and labourers, were considered unnatural. Farmers’ children preferred celibacy to labourers. The increasing longevity of parents reinforced the drift towards late marriage. In 1841 only 6·3 per cent of the population were over 60, by 1901 eleven per cent. Sons, more patient in waiting for a farm than daughters for a man, became relatively older than their brides. This widening age gap meant that a larger number of wives became, in due course, widows. Wives and widows, victims of largely loveless matches, projected their frustrated capacity for affection onto their sons, and contemplated with dread the prospect of a ‘rival’ daughter-in-law who might supplant them in their sons’ affections. The farmers’ wives gave a grimly ironic twist to Parnell’s famous warning ‘keep a firm grip on your homesteads’. To farming mothers the daughter-in-law posed a more pernicious threat than the landlord, and many a mother devoted her later life sapping her son’s will to relegate her to the end room in favour of another woman. As a result the proportion of female farmers, frequently widows refusing to make over the farm to a son, rose from 4 to 15 per cent between 1841 and 1911.

The Churches, particularly the Catholic Church, are frequently criticised for contributing to the unnatural marriage patterns in post-famine Ireland by treating sex as a satanic snare and exalting the virtues of celibacy. The Churches, however, merely reflected the dominant economic values of post-famine rural society. ‘The average Irish peasant’, it was observed, ‘takes unto himself a mate with as clear a head, as placid a heart and as steady a nerve as if he were buying a cow at Ballinasloe Fair’. Few societies anywhere, rural or urban, Christian or Confucian, refined the marriage bargain to such an acquisitive nicety. The integrity of the family was ruthlessly sacrificed, generation after generation, to the priority of economic man, to the rationale of the economic calculus. Priests and parsons, products and prisoners of the same society, dutifully sanctified this mercenary ethos, but they were in any case powerless to challenge the primacy of economic man over the Irish countryside. Clergymen played useful roles as psychological safety valves by helping to reconcile the celibate to their condition. Protestant illegitimacy rates, though slightly higher than Catholic, were distinctly lower than in the rest of the United Kingdom, or, indeed, than in most continental Catholic communities. In the comparative context, the similarities between the sexual and marital mores of Irish Catholics and Protestants were far more striking than the local differences on which polemicists loved to linger. It seems probable that only the consolation offered by the Churches to the celibate victims of economic man prevented lunacy rates, which quadrupled between 1850 and 1914, from rising even more rapidly.

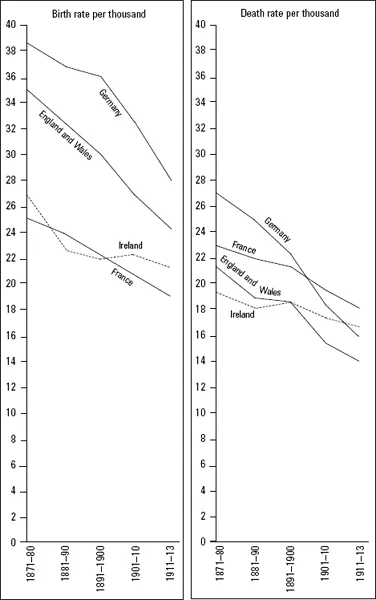

Increasingly late and rare marriage resulted in a fall in crude birth rate (the number of births per 1,000 of the population) from over 35 before the famine to 28 by 1870 and 23 by 1914. Most European societies reduced their birth rate in the late nineteenth century, generally through limiting the size rather than the number of families. In other countries, however, falling death rates helped offset the decline in birth rate. Ironically, this process occurred much more slowly in Ireland, which had one of the lowest normal death rates in Europe, due mainly to a remarkably low infant mortality rate. The pervasive breast feeding of babies, and the nutritious potato diet kept the proportion of deaths among infants in their first year below ten per cent, compared with about twenty per cent in most European countries. The graphs illustrate the exceptional nature of Irish birth and death rates.

A death rate of 17 subtracted from a birth rate of 23, the usual situation between 1890 and 1914, should result in a population increase of 6 per 1,000. Emigration, however, siphoned off more than this natural increase. Close on 2,000,000 emigrants fled between 1848 and 1855; another 3,500,000 followed by 1914. Until 1851 the exodus consisted predominantly of small farmers in family groups. As the number of agricultural holdings stabilised after 1851, farmers’ children and agricultural labourers leaving as individuals replaced family groups as the main source of emigration. The flow declined after the mid-1850s, fluctuating according to the relative prosperity of America and Ireland. Numbers rose to over 100,000 in 1863 and 1864 following bad harvests, fell as low as 30,000 in 1877, when American slump coincided with Irish prosperity, and rose steeply to 96,000 in 1880 when American recovery coincided with Irish depression.

Emigration among labourers reflected more a revolution in their subjective mentalities than in the objective realities of their standard of living. Average weekly agricultural wages rose from 5/- in 1845 to 7/- in 1870 and 11/- in 1914. The crux of the matter was that the rise in the labourer’s standard of living lagged behind the rise in his aspirations. The agricultural labourer who told an enquirer in 1894 ‘I don’t like the work on the land. It is very laborious and does not lead to anything. I have seen men who have worked all their lives as badly off as at the beginning’ expressed the sentiments of thousands of emigrants no longer satisfied with a traditional existence. That the emigration of small farmers was also as much a psychological as an economic phenomenon, that it constituted an aspect of the modernisation of Irish mentalities, can be seen from the persistence into the post-famine period of pre-famine patterns of regional population movements. Emigration was lowest in Connacht, where the survivors, still too poor and backward to contemplate alternatives to traditional existence, lacking both the means and the will to leave, clung tenaciously to their holdings or eked out new ones from waste lands. Connacht emigration rates gradually caught up with the national average by 1870, but not until the agricultural depression after 1877 did the heavy emigration, which has since characterised the province, begin. Between 1871 and 1881 the population of Connacht fell only three per cent, two-thirds the national average, whereas between 1881 and 1891 it fell twelve per cent, one and a half times the national average.

ECONOMIC CHANGE

The flight from the land became widespread throughout western Europe in the late nineteenth century. Irish experience was peculiar mainly because it involved higher emigration, and lower internal migration, than the European average, and because it was the only European country whose rural population actually fell. Why did Ireland, outside the Lagan Valley, fail to create her own Bostons and Birminghams? Why did the population of Belfast increase from 100,000 to 400,000 between 1850 and 1914, while that of Dublin only managed to creep up from 250,000 to 300,000?

The root of the problem in many backward economies lies in agriculture. Food supply constitutes a serious bottleneck because productivity is so low that a sufficient surplus to feed a substantial non-agricultural population cannot be generated. This was not the case in Ireland, which remained a substantial net exporter of food throughout the period. Nevertheless, agriculture made nothing like its potential contribution to economic growth. This failure has been traditionally explained in terms of the switch from tillage to pasture after the famine as ‘the landlord and the bullock drove the people off the land’. The debate on the relative merits of livestock and tillage tends to obscure the fact that both sectors contributed to considerable agricultural progress between 1750 and 1860. Rotation, revolving primarily around the potato, stimulated increases in corn and root yields, which generally compared well with European averages. Density of stocking increased sharply between 1840 and 1860, but it stagnated subsequently. Commercial farming had superseded subsistence agriculture over three-quarters of the country by 1850, when Ireland had one of the most commercially advanced agricultures in the world.

After the famine farmers responded promptly to price movements, which generally favoured livestock more than grain. Profit margins in the livestock sector benefited not only from rapidly rising prices, but also from the fact that production costs rose more slowly in labour-extensive pasture than in labour-intensive tillage. Cattle numbers doubled from 2·7 million in 1848 to 5 million in 1914: sheep numbers, fluctuating violently, rose from 2 million in 1848 to 3·6 million in 1914: poultry numbers, though temporarily decimated in the famine, rose from less than 10 million in 1841 to 27 million in 1914. In 1845 potatoes, grain and livestock each accounted for about one-third of the value of agricultural output. By 1914 the livestock sector contributed three-quarters of the total value. Climate and soil, in contrast to continental experience, allowed the farmer to move exceptionally easily between tillage and livestock and although his gross income from pasture was lower than had he concentrated on tillage, his net income—his prime consideration—fell only slightly below what he could have achieved through a great deal of extra effort. The Irish farmer behaved as a rational economic man, and, after the wave of famine evictions ebbed, it was he, not the landlord, who drove his children and the labourers off the land. But while the farmer behaved rationally within his terms of economic reference, those terms frequently proved dangerously restrictive. As the age of inheritance and the proportion of widows gradually increased, the likelihood of the ‘young’ generation proving receptive to technical progress diminished. The range of efficiency among farmers appears to have been exceptionally wide, and even within the livestock sector the difference between the actual and potential output—had all farmers reached the existing ‘best practice’ standards—seems to have been substantial. The farmer showed more commercial than technical alertness, and it remains unclear to what extent his high leisure preference reflected conscious choice. The propensity for livestock production reduced both the potential rural demand for labour and the potential size of the agricultural market for goods and services; the propensity for inefficient livestock production reduced them still further. A combination of climate and soil on the one hand, and the peculiar family structure on the other, made the potential divergence between individual and collective rationality exceptionally wide in Irish agriculture.

Labour supply posed as few problems as food supply. The supply of unskilled labour obviously exceeded demand, and the supply of skilled labour responded quickly to demand. Scottish and English workers were imported into Belfast to instruct the locals in the mysteries of the machine age, but the natives proved apt apprentices. There is little reason to doubt that the same would have been the case had businessmen attempted to establish major industrial enterprises in other areas. In some sectors, indeed, cheap labour, as James Connolly rightly argued, deprived employers of the stimulus of rising labour costs to increase efficiency.

Recent research has not substantiated the once fashionable belief that lack of capital frustrated industrialisation. In comparison with the requirements for even large-scale manufacturing enterprises, ample amounts of capital were invested in government bonds and municipal loans, or left on sterile deposit in banks. Bank deposits rose from £16 million in 1859 to £33 million in 1877, then stagnated until 1890, before rising to £60 million by 1913. Deposits provide, however, a deceptive index of savings. The increase in the number of branches from 170 in 1845 to 569 in 1880 allowed banks to tap hitherto hoarded savings. Some of the increase in deposits before 1880 simply reflected a transfer of savings from the mattress to the bank safe. Although the average standard of living increased sharply between 1848 and 1877, the actual standard of living rose only slowly. The increase in per capita incomes reflects the artificial impact of the disappearance of the poorest quarter of the population, whose presence had depressed pre-famine averages, without resulting in a remotely comparable increase in the income of the survivors. Bank branches continued to increase to 809 in 1910, but the doubling of deposits in the twenty years before the First World War represents a genuine increase in savings, as new branches were by this stage established mainly in existing banking centres. The alacrity with which Irish purchasers, urban and rural, bought encumbered estates in the 1850s to the value of £20,...