- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

When Women Kill

About this book

A genre-bending feminist account of the lives and crimes of four women who committed the double transgression of murder, violating not only criminal law but also the invisible laws of gender.

When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold analyzes four homicides carried out by Chilean women over the course of the twentieth century. Drawing on her training as a lawyer, Alia Trabucco Zerán offers a nuanced close reading of their lives and crimes, foregoing sensationalism in order to dissect how all four were both perpetrators of violent acts and victims of another, more insidious kind of violence. This radical retelling challenges the archetype of the woman murderer and reveals another narrative, one as disturbing and provocative as the transgressions themselves: What makes women lash out against the restraints of gendered domesticity, and how do we—readers, viewers, the media, the art world, the political establishment—treat them when they do?

Expertly intertwining true crime, critical essay, and research diary, International Booker Prize finalist Alia Trabucco Zerán (The Remainder), in a translation by Sophie Hughes, brings an overdue feminist perspective to the study of deviant women.

When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold analyzes four homicides carried out by Chilean women over the course of the twentieth century. Drawing on her training as a lawyer, Alia Trabucco Zerán offers a nuanced close reading of their lives and crimes, foregoing sensationalism in order to dissect how all four were both perpetrators of violent acts and victims of another, more insidious kind of violence. This radical retelling challenges the archetype of the woman murderer and reveals another narrative, one as disturbing and provocative as the transgressions themselves: What makes women lash out against the restraints of gendered domesticity, and how do we—readers, viewers, the media, the art world, the political establishment—treat them when they do?

Expertly intertwining true crime, critical essay, and research diary, International Booker Prize finalist Alia Trabucco Zerán (The Remainder), in a translation by Sophie Hughes, brings an overdue feminist perspective to the study of deviant women.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Approaching Silence

MARÍA CAROLINA GEEL

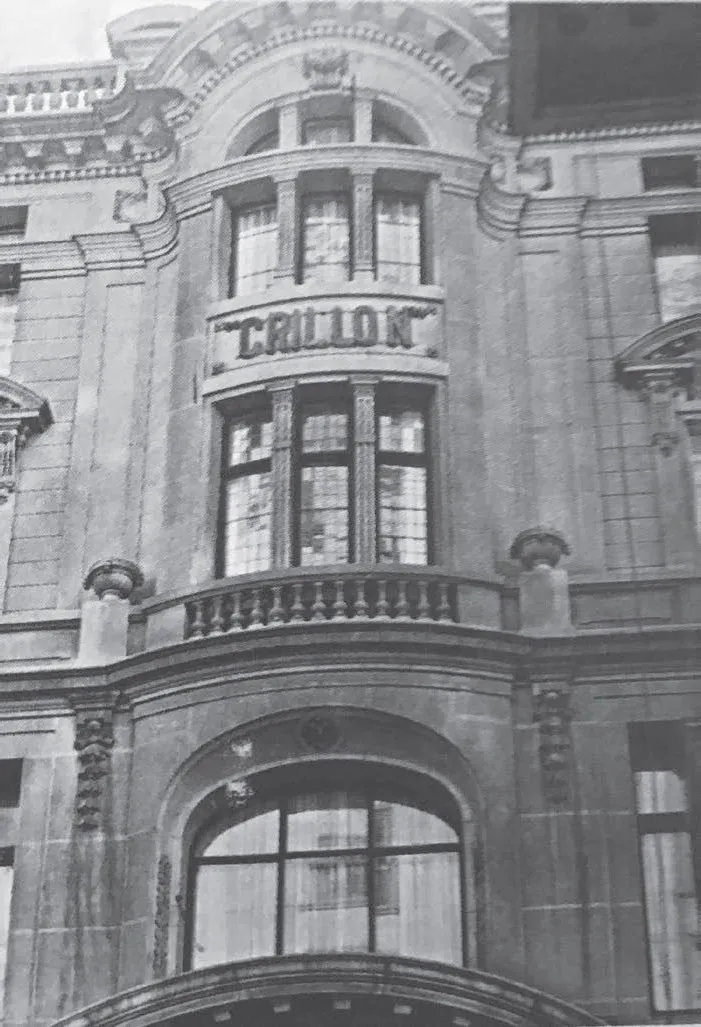

María Carolina Geel puts on a pair of hoop earrings, a silver bracelet, and her long beige coat before slipping a pack of cigarettes into her pocket, followed by the weighty revolver she bought a few days earlier. She leaves her apartment in the center of Santiago and walks, at a leisurely pace, to the tearoom at the Hotel Crillón.

Inside the hotel’s airy dining room, surrounded by white tablecloths, teardrop chandeliers, and dainty porcelain tea sets, young Roberto Pumarino, dressed in a suit and tie, waits for her. They met five years earlier at the Caja de Empleados Públicos y Periodistas (Civil Servants and Press Pension Fund), where Geel was the only female stenographer and Pumarino a married man who wooed her with smiles and gifts. Having seduced her, and after separating from his wife, he and Geel struck up a romantic relationship. Their relationship would run smoothly until that Thursday, April 14, 1955.

That afternoon, like so many before it, Roberto and Carolina greet each other warmly before tucking themselves away in a quiet corner of the busy restaurant. Geel sits with her back to Santiago’s rowdy bourgeoisie, for whom the hotel is a regular haunt, and Pumarino squeezes into a seat in the tight space between the table and the wall. They decide to order a full tea: cakes, fruit, jams, and bread. They talk softly amid the raucous chatter and laughter around them. At the next table, the writer Matilde Ladrón de Guevara casts sideways glances at the discreet diners while pretending to listen to her sister Lucía’s latest news. She recognizes Geel, a fellow writer, but decides not to bother her. Days later, when questioned about what she saw and heard in that crowded hotel, Ladrón de Guevara will claim that there was something about Geel’s appearance that unsettled her: the strange look on her face, her strong, powerful expression—“the look of a fanatical person,” she will tell the court officer.

Far from fanatical, however, Geel did not raise her voice that afternoon. Ronaldo Fuentes, their waiter, never heard the couple arguing, nor did the other witnesses perceive any kind of conflict. In fact, Roberto Pumarino must have believed that his companion, his darling “girl,” was about to produce a cigarette, perhaps a handkerchief, or a pencil to jot down an idea; he might have imagined anything but the 6.35 mm caliber Belgian pistol that she would pull from her pocket and aim directly at his face. Geel squeezed the trigger repeatedly until the hammer made only an empty, hollow sound. Five shots, all on target. Twenty-eight-year-old Roberto Pumarino was killed on the spot.

After the shooting, amid panicked screams and wailing, an ashen Geel stood up from her chair and silently contemplated the scene of the crime. As if the gunfire had ripped a hole in time and space, she appeared to be incapable of hearing anything beyond her own breathing. “The writer,” a note in Vea magazine would point out, “without uttering a word, without so much as twitching, as if she were somewhere else entirely, simply stood there before the most tragic chapter from the novel of her life.”

Nobody moved until the journalists came storming into the room. They were used to meeting local celebrities there and were at the hotel in a matter of minutes. Equipped with large cameras and flashes, the photographers captured Roberto Pumarino’s bloody body: closed eyes, bent head, lifeless arms, and his tie all askew.

The photographers also took impressive images of the female perpetrator: impassive, as if wandering alone through some far-off landscape. The reporters, on the other hand, did not get what they were after. Beside the corpse, Geel appeared not to hear their questions and accusations. “María Carolina Geel responded in faltering monosyllables,” one disappointed journalist reported in Clarín. “She did not reveal the exact motive for her crime,” wrote another in Las Últimas Noticias.

The writer was escorted to a car by the police and immediately driven to the nearest police station. On the way, she was subjected to the first of many interrogations. Name? Profession? Marital status? Age? “Eighty-eight, forty-one, one hundred and sixteen,” Geel garbled, staring into space. And she carried on staring in response to the most difficult—and important—question: Why? A single syllable that would be repeated for months as she stubbornly refused to answer it.

[Diary of the silence]Here, in my hands, is the court ruling against María Carolina Geel. Its pages are stitched together with thread; a fault in the typewriter has caused a little ink blot every time the letter l appears. It took me weeks to find this document. It’s in shreds, I was warned. Lost, destroyed, water-damaged. And yet, here it is. I go over the names embossed on the cover of the file, Geel’s alternate and, in the eyes of the law, legitimate identity: Georgina Silva Jiménez. But my anxiousness soon gets the better of me and I start leafing through its pages looking for a sign. I, too, just like the journalists and detectives, want to uncover her secret, her truth. I turn the first page, then the second and third. And it is like entering a dark room in the certainty that someone is inside, just a step away, a step further, and another.

Forty-one years earlier, María Carolina Geel had been christened with the somewhat less literary name of Georgina Silva Jiménez. The youngest of six children, her childhood had not been easy after her father’s untimely death and the family’s financial ruin. By the age of fifteen, desperate to leave the family home, she had already married her first husband, Pedro Echeverría, with whom she had one child, a son. But the author would describe it as an unhappy marriage; ultimately it broke down, according to Echeverría, due to irreconcilable differences. After separating and annulling their marriage—taking advantage of a legal loophole—Geel went on to try married life a second time. But after five disastrous months with her second husband, she once again annulled the union, stashed her ring away in a drawer, and promised herself that she would never again make the same mistake.

During this whole period, Geel wrote tirelessly. Before committing the murder, she had already published three novels and an important essay, “Siete Escrituras Chilenas,” in which she surveyed the work of her female contemporaries: writers such as Gabriela Mistral, Marta Brunet, and her favorite, María Luisa Bombal. She also worked as a stenographer and a recording secretary, in addition to writing columns and reviews for various literary supplements. She was, by all accounts, an independent and modern woman, a well-known cultural figure. And then, one day, she was a murderer, too.

The Crime at the Hotel Crillón, as the newspapers dubbed it, received unprecedented media coverage. From the outset, the press devoted long reports to the murder, but none of the unfolding coverage could deliver a statement from the culprit herself. Geel did not utter a word to reporters either before or during the heavily publicized trial. And this refusal to speak about the crime was echoed in the courtrooms. Throughout the criminal proceedings against her, Geel was interrogated by detectives, court clerks, judges, lawyers, and a sizeable team of psychologists and psychiatrists whose questions the author obligingly answered: she went over her daily routine as a writer, her relationship with Roberto Pumarino, the causes of her previous two separations, and even the precarious state of her finances. She spoke without trepidation about every area of her life except one: the murder. “The author initially refused to testify at all, and later claimed that she did not know why she had committed the crime; she spoke vaguely and in broken sentences,” states one item in the court ruling.

Roberto Pumarino’s murder was presented as an unfathomable mystery by its very perpetrator. Geel was evasive toward the judge and court clerks and refused to reveal the reasons for her actions to reporters. But the mere idea of a motiveless crime, of an unprovoked murder committed by a woman, was unimaginable for Chileans in the 1950s. The press drew their own conclusions from Geel’s resolute silence. “She killed, mad with love,” was the tabloid newspaper Clarín’s headline the day after the crime, while the magazine Vea ran with: “A love affair’s dramatic conclusion.”

Within the space of a few hours, and entirely disregarding Silva Jiménez’s silence, the newspapers all settled on the same motives for her crime: love, jealousy, delirium. A timeless, ready-made tale that required no evidence, and which, to this day, is still seen as the indisputable truth behind the crime at the Hotel Crillón. Today, wherever the case is brought up in news reports or documentaries, the same old sentiments are dredged up. “Jealousy” and “madness,” repeated so often as to be inscribed into women’s very makeup, provided a devastatingly efficient explanation for such a violent murder. Irrespective of their editorial lines, media outlets all described a woman desperate for a man’s love, jealous of another lover, and unstable to the point of pulling the trigger on him for no apparent reason. A few days after the crime took place, the magazine Vea published the following lines regarding the homicide: “Things happen for a reason. These are the times we live in: gone are the days when women would drink vinegar in order to faint like damsels before their cheating partners. No, now they wield automatic pistols and settle hateful betrayals with bullets.”

The article is a faithful reflection of the anxieties of the 1950s, a period of upheaval which, three years earlier, had seen women first participate in a general election and enter a working world hitherto beyond their reach. Feminism had dominated public debate in the previous decade, and Geel—not only a working, twice-separated writer, but a violent woman to boot—embodied the very worst fears around what female emancipation might lead to: armed women.

Within this context, and in order to explain an ostensibly inexplicable act of violence, one about which its perpetrator refused to say a word, the press turned—as in the case of Corina Rojas, Rosa Faúndez, and so many contemporary women—to love. What better than love and its manifestation—jealousy—to normalize not only the female killer but also the independent and twice-separated woman who refused to explain her deadly behavior. The press even makes allusions to the femme fatale in their tireless campaign to normalize Geel. Her red lips, her passion, the gunshots, and the writer’s physical attractiveness all lent Geel the air of a deadly woman: the living embodiment of the male fear of unchecked female sexuality.

This explanation did not satisfy Judge Aliro Velos, however. Having pondered the arguments from the prosecution and defense, and having read the newspaper reports, he demanded new evidence be brought forward. He needed more than alleged jealous outbursts to convict María Carolina Geel of a murder that had bloodied the very rooms where he himself took tea some autumn afternoons. For Geel, the model of a modern woman, to kill a man at gunshot and then refuse to reveal her motives was simply unacceptable. The judge would obtain a confession at all costs.

[Diary of the silence]I try to stick to the words written on the page and to speculate as little as possible, but the deeper I go into the court ruling, the less clearly I hear her voice. I try to imagine what Geel must have felt as she pulled the trigger and I wonder if I would ever be capable of doing something like that. Restless, I decide to copy her medical history into my notebook. “Psychosis on the part of a maternal aunt, now deceased,” says the judge accusingly, “the suicide of one of her mother’s cousins, another incarcerated.” And the case of Elia, her sister, “who has suffered from psychosis and in the past has required hospitalization.” Her family history is damning: weird, depressed, locked-up women. The seed of the crime already ran in her blood, her lawyers suggest, but their speculations aren’t enough to convince me. In fact, the longer the list of motives grows, the less the final ruling makes sense to me. Nor am I convinced about her helplessness or confusion. For the first time, I’m worried I might come to the end of my research without any answers at all.

María Carolina Geel declared throughout the trial that the murder was not planned, that she had no particular motive for committing the crime, that perhaps she had been thinking of attempting to kill herself, that at no time had she felt desperate, but that yes, it was true that she was deeply unhappy. The ruling itself states that it had proved impossible to determine the true reasons for her behavior, which is why the first sentence in the court verdict is so alarming. First describing her as a forty-two-year-old woman, single, a writer, and a first-time offender, the ruling goes on to state that the accused confessed. That is, according to the legal definition of a confession, Geel must have acknowledged, incriminating herself, the truth about the crime.

But, strictly speaking, María Carolina Geel never confessed. She never disclosed the motives for her murderous behavior. What she did, uttering a single syllable, was admit. And what she admitted to was having perpetrated a murder in a public place, in broad daylight, with dozens of witnesses. The magistrate asked: “Did you shoot Roberto Pumarino?” And Geel responded: “Yes, I did.” However desperately the magistrate sought to find a cause and reason for the crime, this admission does not constitute a full confession because Geel, with those three words, does not reveal her truth—a truth that, however subjective and fragile it may appear, was crucial for the judge to be able to justify a future punishment.

The French philosopher Michel Foucault tells the story of a similar case in order to illustrate the importance of confession in modern criminal proceedings. A man accused of committing murder goes to court to hear the verdict. Like Geel, the defendant admits to having committed the murder and attends the hearing to learn his punishment. But the judges demand more from him than a mere admission: they want the man to reveal his motives. They interrogate him, raise their voices, lose their patience, but the man replies only with unbreakable silence. And that silence, so similar to Geel’s, puts the court in a predicament that Foucault pond...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for The Remainder

- Also by Alia Trabucco Zerán

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Translator’s Note: The Story Behind the English Title

- Prologue: Outside the Law

- A Death for Her Heart: Corina Rojas

- Under Wrath’s Sway: Rosa Faúndez

- Approaching Silence: María Carolina Geel

- Part of the Family: María Teresa Alfaro

- Epilogue: The Theater of Punishment

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Funder Acknowledgments

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access When Women Kill by Alia Trabucco Zerán, Sophie Hughes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.