![]()

1

VIENNA WAS WARM AND WELCOMING that June and, thanks to letters of introduction I was immediately allowed access to the dimly lit Studiensaal of the Graphische Sammlung Albertina, home of the world's greatest collection of Schiele drawings and watercolors, as well as the depository for a rich archive of Schiele sketchbooks, photographs, letters, postcards, and pertinent newspaper articles. I worked there daily for six weeks, becoming acquainted not only with Schiele's artwork but also learning to read his handwriting—the old Kurrentschrift, which at first glance looks like a string of Gothic m's and w's all run together. I might have despaired of ever breaking the cursive code except for the fact that formidable help was at hand. Max Mell, a venerable Viennese playwright and friend of my mother, solicitously wrote out a Kurrentschrift alphabet for me.

In July, Julius Held arrived in Vienna along with Professor Harry Bober of New York University's Institute of Fine Arts to teach a joint course on illuminated manuscripts. I accompanied the class on visits to the National Library to observe preservation techniques, and we saw the Dioscurides being restored—that magnificent, sixth-century manuscript on medicinal plants created for the immensely wealthy and learned dowager, Anicia Juliana. We learned that she considered mighty Emperor Justinian of the great Ravenna mosaics as a mere "upstart puppy." I had seen those impressive mosaics at the Church of San Vitale when I was a teenager in Italy one summer, and I marveled at this unexpected insight into the shifting sands of reputation across the centuries.

Julius introduced me to the art historian Werner Hofmann, director of Vienna's new Museum of the 20th Century (Museum des 20 Jahrhunderts), and he in turn sent me to meet the contemporary sculptor Fritz Wotruba, an ardent and articulate collector of Schiele drawings. He delivered gruff salvos about Expressionism's impact on later generations, and I couldn't help but imitate his buckshot style of speech—an acoustical impudence that amused him. It was Wotruba who designed the large bold cube standing on end that marks Schönberg's grave in Vienna's Central Cemetery and which, he told me, is pointedly placed vis-à-vis the Dr. Karl Lueger Memorial Church: "der schöne Karl"—that handsome, popular, anti-Semitic mayor of Vienna from 1897 to 1910 who, nevertheless, courted wealthy Jewish industrialists, justifying his actions with the blunt dictum: "Wer ein Jud ist, das bestimm ich" ("I decide who is Jewish").

Back at the Albertina Museum, Julius gamely helped me decipher Schiele's diary of 1916, patiently reading aloud the as yet unyielding Kurrentschrift for several afternoons while I took notes. Herschel Chipp came to Vienna for a few days and sat with us in the Studiensaal as we continued to peruse Schiele's diary. It suddenly dawned upon us that the mysterious o's populating the diary stood for the number of times the artist slept with his wife Edith. I photographed Julius and Herschel that evening as we sat around a table relating this "scholarly" detection to a bemused Werner Hofmann (FIG. 2).

At the end of July, I accompanied Julius on a weekend flight to Milan where he needed to look at eight unpublished Rubens drawings in the Ambrosiana Library. Because Julius was ever on the lookout to acquire art for J. Paul Getty's new museum in Ponce, Puerto Rico, we also visited several dealers whose Baroque paintings Julius scrutinized with his usual aplomb. I solemnly translated his ex cathedra pronouncements into florid Italian for the gallery owners. Fixated on things Austrian, and Egon Schiele in particular, however, I felt strangely impatient with Italian effusiveness and was eager to climb back inside the intriguing time capsule I had elected to explore in Vienna.

Nevertheless, I did discover a contemporary Austrian artist in Italy: Friedrich Hundertwasser (he later changed his first name to Friedensreich), then living in Venice and highly regarded by the Italians. Reproductions of his wry, brightly colored mosaic-like images were everywhere. I returned to Vienna with twenty postcards and wrote him a spontaneous letter of appreciation, declaring how struck I was by his use of decorative motifs that seemed to render homage to Vienna's foremost painter of the Art Nouveau generation, Gustav Klimt. Almost by return mail a charming letter arrived from him, readily acknowledging the Klimt debt and inviting me to visit.

FIG. 2

Art historians Julius Held, Herschel Chipp, and Werner Hofmann. Vienna, 13 August 1963. Photograph by the author.

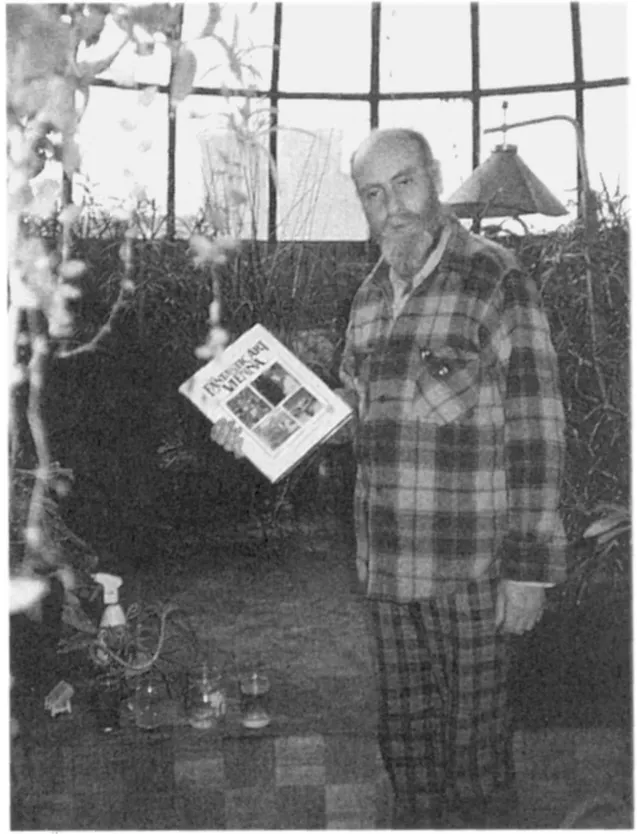

FIG. 3

The artist Friedrich Hundertwasser in front of his urine purification system holding a copy of the author's book The Fantastic Art of Vienna. Vienna, 13 October 1981. Photograph by the author.

This began an intriguing, slightly combative friendship, in which he tried to convert me to the Zen philosophy behind his ambitious ecology projects in Uganda and New Zealand, and I attempted to demonstrate how sexist his language and outlook were. Three of his kaleidoscopic, multipatterned microcosms embellish the final pages of a book I wrote in 1978, The Fantastic Art of Vienna. On a visit to Hundertwasser's Vienna studio three years later, at an urgent invitation to see his "humus toilet," he proudly posed with a copy of the book in front of the tiered plant arrangement he employed to purify his urine (FIG. 3). I treasure his note reporting on a speech he'd just given at the United Nations in December 1983 on the occasion of the release of his specially commissioned United Nations human rights stamp: "In respect to your critique that I leave out half of humanity in my writings, I used the words 'men and women' instead of 'man' throughout my address."

We discovered we did agree on one thing: that it was a shame the city of Vienna was tearing up the old double-headed eagle bricks paving the Karlsplatz—weighty relics of imperial times past—and we each rescued several of the roseate bricks for our personal collections. The one I mailed back to America is hand-decorated by Hundertwasser with a spiraling balloon, dedication, and date. A few of these bricks can be recognized in the artist's imposing three-dimensional achievement—his slap in the face of "dehumanized" modern architecture with its straight lines, the Hundertwasser Haus of 1985. Located on Vienna's otherwise lackluster Löwengasse in the Third District, it is an imaginative onion-domed fifty-unit apartment complex of roof gardens and cascading terraces graced with shrubs and trees overlooking color-coded flats distinguished by wavy hand-drawn lines and individuated windows. Hundertwasser lived long enough to see it become one of Vienna's most popular tourist sites.

![]()

2

WORKING IN THE ALBERTINA during that first summer of research in 1963, I realized that eleven of the thirteen known watercolors Schiele had created while in prison were in the museum's collection. I examined them carefully—each one framed in an individual white mat with the Albertina imprint—and took copious notes in pencil. Following Bernard Berenson's connoisseurship example, about which I had just learned at Berkeley, I made an annotated sketch for myself of every artwork, attempting to develop a feeling for the hand of the artist—something that would later be immensely helpful in spotting Schiele forgeries.

Unbidden, quotations from the diary Schiele had kept during his incarceration peppered my dreams as I began to identify with Schiele's imprisonment and the one thing that sustained him, his art: "Yesterday: cries—soft, timid, wailing; screams—loud, urgent, imploring; groaning sobs—desperate, fearfully desperate. Finally apathetic stretching out with cold limbs, deathly afraid, bathed in shivering sweat. And yet, for my art and for my loved ones I will gladly endure to the end." This final line became the title for the last of Schiele's four prison self-portraits and seems to have marked a turning point in attitude, as with new resolve the artist faced his unknown future.

Self-proclaimed Schiele cognoscenti as well as several of the watchful Albertina guards (who referred to me as "das Schiele Fräulein") took an avuncular interest in my work but—uniformly—everyone counseled me not to bother interviewing the artist's two still-living sisters. They were confirmed recluses, did not even speak to each other, and were, in short, crazy—"verrückt." Nothing could have been more of a challenge to me than such negative counsel, and soon I mailed off two carefully composed letters of self-introduction to Melanie and Gertrude, whom I already felt I had gotten to know from Schiele's portraits of them, begging for the privilege of an interview.

While waiting for possible answers to my letters, I decided to explore some nearby Schiele "sites"—first, his birthplace in the small railroad stop of Tulln on the Danube where his father had been stationmaster, second, Klosterneuburg, location of Schiele's school and first drawing lessons, and third, the village where he had been imprisoned, Neulengbach. The art historian Otto Benesch, just retired from several decades as the Albertina's redoubtable director, gave me an extended interview concerning the sympathetic young artist who exactly fifty years earlier had painted him as the seventeen-year-old son in an intriguing double-portrait statement on tensions within a father-son relationship. Benesch had never been to Schiele's prison; in fact, I soon ascertained that no one connected with Schiele—neither his relatives nor his chroniclers—had gone to Neulengbach since the artist's release in 1912.

And so on the morning of 27 August I rented a Volkswagen and drove to Tulln, then to Klosterneuburg, where I sought out the widow of Schiele's first drawing teacher and photographed some of her husband's work, and finally down to Neulengbach, thirty miles southwest of Vienna. I was armed with a letter of introduction from the Albertina's director, Walter Koschatzky, asking that cooperation be extended to me. This letter on embossed museum stationery turned out to be an unexpected liability, however, when I presented it to the uniformed official on duty at Neulengbach's district courthouse. The man read my letter out loud very slowly, emphasizing with mock reverence the words "Albertina," "Direktor," and "Wien." Then, abruptly, he waved me away like an insect, declaring that it was quite impossible for me to enter the building as there were, solemn pause, "wichtige Regierungspapiere" ("important government papers") stored inside. No pleading on my part had any effect, and sadly...