![]()

1. BIOGRAPHY

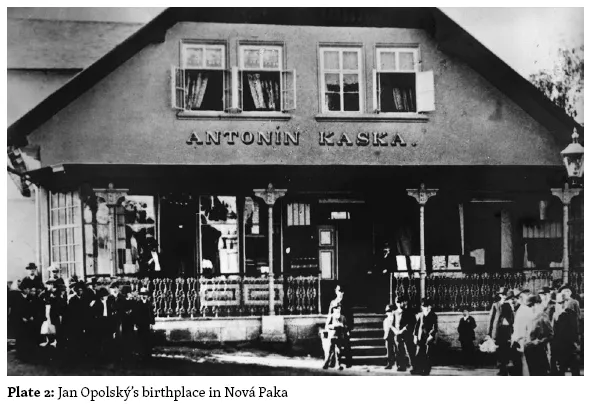

Jan Opolský was born on 15 July 1875, in the small north-eastern Bohemian town of Nová Paka, as the son of Josef Opolský, a solicitor’s clerk, and his wife Kateřina née Menčíková. Both parents came from working-class families. Josef Opolský was the son of a saddler from the nearby town of Nový Bydžov, and Kateřina was the daughter of a local confectioner and gingerbread-maker. The couple had three sons, of whom Jan was the second-born.

The family seems to have been harmonious, at least initially. Kateřina was an attentive mother who took the upbringing and education of her children seriously. It is to her credit that they were all taught to read and write before going to school. As a result of this early learning Jan was able to skip the first year at primary school after only three weeks. The rest of his school career, as far as it went, was remarkably successful and his standard of achievement consistently high.7 After completing the basic nine-year course, he was ready to leave school on his thirteenth birthday. By this time he had developed a strong interest in art and handicraft and decided to become an engraver. He applied for an apprenticeship but was rejected because he was too young. Granted permission to stay on at school for another year, he hoped to succeed in his application second time round. But this was not to be. A year later, Opolský’s father was already considerably less sympathetic to the idea of an apprenticeship, especially in a field in which there was no family tradition, and decided that it was time for his son to start earning a living. It is quite possible that his attitude was influenced by the critical situation which had developed at home. When Jan was ten years old, Kateřina died in her late thirties, leaving her husband to rear three children single-handed. This was in addition to the problems he already had trying to salvage the business of his negligent boss.

The search for employment led Jan Opolský to the commercial art studio of Václav Kretschmer, where he found a job that did not require formal training but nonetheless allowed him to use his natural artistic skills. It is hardly likely that Opolský found this work profoundly satisfying, even though he was to remain with Václav Kretschmer for a full twenty-five years. Kretschmer’s studio was run on a strictly mercantile basis, churning out standard items of religious art, such as icons and gilded statuettes, but also, mainly to order, secular works such as landscapes, portraits, still-lifes and genre paintings. Many years later, Opolský reminisces sardonically:

Všech dílen, co jich na světě je, ta dílna byla vzorem,

neb co se dalo malovat, to mastili jsme skorem.

My robili jsme landšafty a portréty,

jež měly to vlastnost, že jsme obětí svých nikdy neviděli.

My malovali ikony, i žánry, jež jsou k tomu,

by krášlily svým humorem zdi měšťanského domu.

My tenkrát všecko uměli a mám na to dost svědků,

že překrásná už madona tak stála u nás pětku.

My malovali amóry. A zátiší. A báby,

a fortel měli na plátně tak jako na hedvábí.

No universum hotové, se dalo prostě říci,

a dřeli jsme to od kusu tak jako soustružníci.8

The eight employees were paid by the piece and worked from eight to twelve and from one to six every day.9 There was no room for creative inspiration; all that was required was routine, technically proficient craftsmanship. As the literary historian Bedřich Slavík, later a close friend of Opolský’s, comments euphemistically:

Při malbě nešlo o individuální vlohy a umělecký vývoj, ale časem se u malířů vyvinula zručnost mnohem podobná dovednosti středověkých řemeslníků.10

The painters worked in a team, each one specializing in certain aspects of the task: one would mix the paint, another would draw the outlines, another would paint hands and faces, another clothing, another background and so on, according to a system originally evolved by early Flemish painters. However, for all its dull routine, the workshop produced several artists of note, such as Bohumír Číla and Karel Havlata.11

At the age of nineteen, after five years with Václav Kretschmer, Opolský lost his father, who died suddenly in his late forties. Now orphaned, he not only was left to his own resources but also carried the responsibility of looking after his younger brother. There followed a period of hardship and loneliness. However, Opolský soon succeeded in overcoming this isolation and forming a circle of friends. Many of them were older than Opolský, and were probably as much fatherly mentors as friends. Among them were several of Opolský’s former teachers: Vilém Polák, for example, headmaster of the local primary school and a musician of sorts; and Josef Nováček, languages and history master at the secondary school, whose English wife lent the studious youngster books from her private library and acquainted him with the works of Dickens and Meredith, as well as other works of English and European literature. Then there was Břetislav Jampílek, also a schoolmaster, something of a philosopher, but with theosophist leanings. Last but not least, there was Opolský’s former classmate, the ironmonger Josef Anton, who had the largest library in the district and who ran a family table-top puppet theatre (‘stolní rodinné divadlo’). Later on, Opolský was to make friends with two well-known writers resident locally, Karel Sezima and Josef Karel Šlejhar. He also became acquainted with the painter Josef Tulka and the sculptor Stanislav Sucharda.12

It was largely through the influence of these friends that Opolský began to evolve an extensive audodidactic activity. He eagerly consumed large quantities of literature both domestic and foreign. He regularly read the literary periodicals Rozhledy, Lumír and Moderní revue, to which he also began to contribute poetry, and acquainted himself with the work of Jiří Karásek, Karel Hlaváček, Antonín Sova, Otokar Březina and Julius Zeyer. His favourite writers, however, were Garborg, Hamsun, Flaubert, Rilke and Dehmel, especially Gautier, Dostoevsky and Gogol. In addition, he read numerous works on art history, above all on Renaissance and Baroque art and developed an interest in the Dutch, German and Italian masters.13

Opolský became something of a local character. Sezima has given us a charming vignette of Opolský, habitually clad in a long sleeveless hooded coat and a wide-brimmed hat, striding along the arcade around the main square of Nová Paka on his daily walk to his favourite watering-place, the ‘Snake’s Grotto’, where he enjoyed the regard of local malcontents:

Básník denně, za každého počasí prošel ve svém věčném haveloku a karbonářském širáku podloubím, po jedné straně vroubícím náměstí mířil do své demokratické hospůdky, obecně nazývané ‘Hadí Slují’. Bylo tam dostaveníčko mistrů ševců novopackých a vůbec doupě místních nespokojených živlů, Opolský požíval mezi nimi značné autority.14

The Snake’s Grotto was so named after a room at the rear that was hewn into the local sandstone like a cave. One wonders how many readers of his poem ‘Hadí král’ in Svět smutných saw the joke when he wrote:

Zde bylo k smrti úzko za noci!

Ta černá sluj, v níž kapraď vyhnívala,

kam vlét-li pták, už zhynul bez moci,

kde voda zelená se zabublati bála!

Opolský’s daily quota of beer in the ‘Snake’s Grotto’ was a pleasure he could hardly afford on his meagre wages, which meant he had to save on clothes and shoes. As his niece Jiřina Brabcová recalls:

[. . .] měl zlatku denně. To bylo málo, byl pivapitel, tedy vypil řadu pullitrů, a i když stál půllitr piva šest krejcarů, bylo to denně dost a nezbylo často ani na opravu bot, tím méně na doplnění prádla15

adding that her grandmother often had to go to the pub and pay for the drinks Opolský had put on tick.

Besides material hardship, the young Opolský was also afflicted by recurrent ill health. The basic complaint seems to have been a weak heart, although there may have been other contributory factors. He spent frequent periods in hospital in Jičín, the provincial capital, between the spring of 1895 and the summer of 1897. Often he was bed-ridden for several months at a time. However, by physical exercise and particularly by participating in the activities of the nationalist gymnastic association Sokol, he improved his state of health to such an extent that, in early 1899, he was found fit for military service.

At the beginning of April 1899 he was called up to serve with the 74th infantery regiment at Jičín. The experience of army life seems to have had a disconcerting effect on the young recruit. In a letter to his girlfriend, Františka Endová, he describes his impression of his first weeks’ military service:

Minulé dny ztratily se pro mne jako plachý dým, a není ničeho než hrubého a bezduchého dření.16

But it was less the stultifying grind of army routine or the physical strain of military drill that distressed Opolský than the coarse atmosphere:

Jsem otráven více surovým ovzduším, nežli velikým tělesným dřením.17

In June 1901, Opolský was transferred from Jičín to Liberec, but the regiment and barracks in Liberec were, if anything, worse than those at Jičín.

Throughout his military service Opolský maintained a regular correspondence with Františka Endová, whom he had met originally at a dancing lesson in Nová Paka, and to whom he later became engaged. His relationship with Františka, the daughter of a well-to-do clothier, was the source of much hostility and resentment locally. Malicious gossipmongers had soon spread the conjecture that the indigent young suitor was only after his fiancée’s money and social position. Opolský took these accusations very much to heart, and, at one point, even considered leaving Nová ...