- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prague Soundscapes

About this book

Dvorák's opera Rusalka at the National Theatre. A punk concert in an underground club. The hypnotic chanting of Hare Krishnas joyfully dancing through the streets. These are the sounds of Prague. And in this book, they are the subject of a musical anthropological inquiry.

Prague Soundscapes seeks to understand why in human society—in its behavior, values, and relationships—music is produced and how those who make it listen to it. Based on recent theories of cultural anthropology, this study offers an account of the musical activities of contemporary Prague in different musical genres, cultural spaces, and events. The text is bolstered by color photographs of the musical events, producers, and listeners.

Prague Soundscapes seeks to understand why in human society—in its behavior, values, and relationships—music is produced and how those who make it listen to it. Based on recent theories of cultural anthropology, this study offers an account of the musical activities of contemporary Prague in different musical genres, cultural spaces, and events. The text is bolstered by color photographs of the musical events, producers, and listeners.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

LISTENING TO THE MUSIC OF A CITY

LISTENING TO THE MUSIC OF A CITY

Prague Soundscapes is about the music in Prague through the ears of ethnomusicologists. As my student Petra once said, “When someone has been through ethnomusicological schooling, he never listens to music the same way as before.” This apparently banal truth (after all, every experience we have changes further ones) is particularly valid in the case of music: we perceive it so intimately, and are so used to approaching through the categories of “like” vs. “don’t like” that we experience a change in approach as an attack on our personal integrity. However, this is exactly how ethnomusicology works: whether or not you like certain music is not the main issue. You have to understand why it is the way it is. For an ethnomusicologist, listening means trying to understand.

From our point of view, ethnomusicology is more or less synonymous with musical anthropology. We thus seek the answer to that WHY in human society – in its behavior, values, and relationships. However, as is often the case in science, there is no universal theory, or even a universal concept clarifying what exactly music is. From the ethnomusicological perspective, it is not only sound, but also – and in fact primarily – the people who produce and listen to it and the way in which they do so, that is fundamental. It is the world around sound. The musical world.

Imagining this is not always entirely simple. In order to clarify our perspective, we begin this book with theoretical considerations. In the second part of the first chapter, we then describe the process of writing this book. Each of the following six chapters is connected to a single anthropological phenomenon which we are convinced is related to the shape of music. And in fact, these connections are the main theme of our book.

A bonus awaits attentive and empathetic readers: it often happens (and it has also repeatedly happened to us) that when we understand why music sounds exactly the way it does, we like it. It becomes our music.

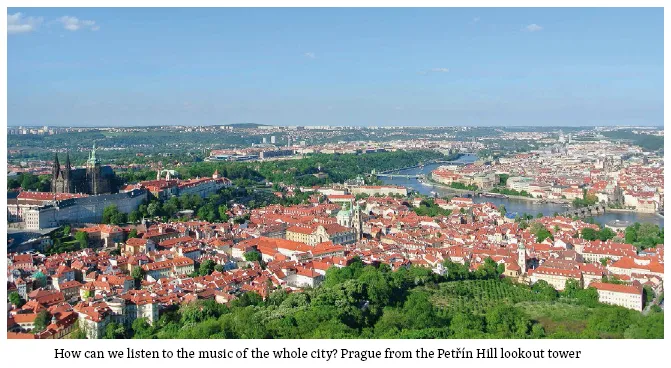

FOR THOSE WHO DO NOT WANT TO WASTE TIME ON THEORY

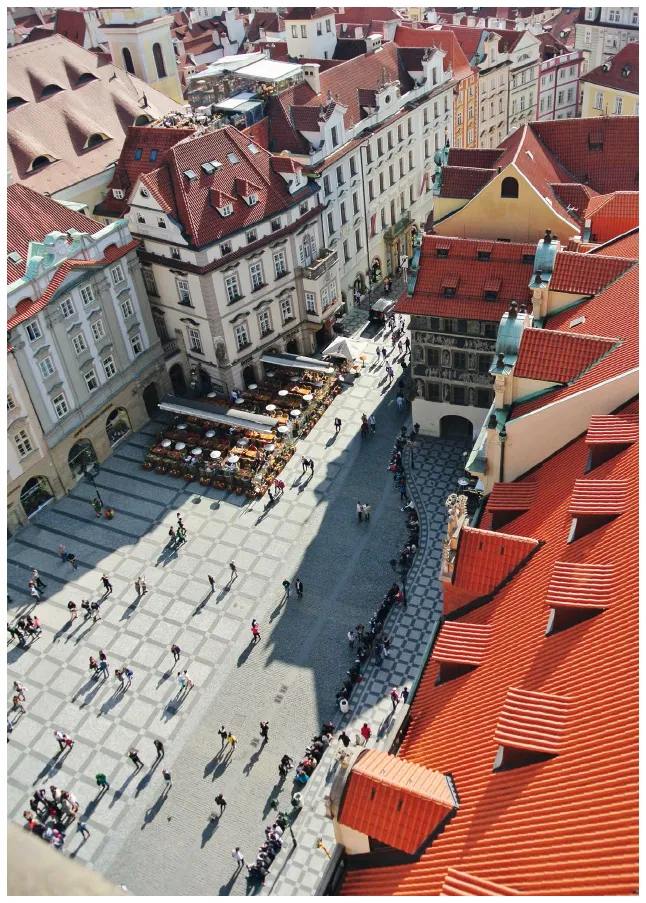

We imagined music in Prague as a set of musical worlds (for which the word soundscapes is sometimes used): worlds of people who perform and listen to a certain type of music; worlds whose boundaries are, however, vague. In addition to having unclear boundaries, these worlds are permeated from various sides by global factors both those of a technical and economic character and those of thoughts and images. And so the Prague soundscape is full of streams of individuals, all of which are constantly merging and influencing one another, the sounds they produce, and meanings with which they connect those sounds.

FOR THOSE WHO ARE NOT AFRAID OF THEORY

Our topic originally appeared to be simply arranged along three axes: people (who listen) – music (which they listen to) – and place (where they listen). It looked as though we wanted to describe a three-dimensional reality – certainly not an easy task, but at least an understandable and transparent one. Besides, concepts for this reality exist that may help us, at least a bit.

The key concept, in the English-language literature (and also in several Czech texts), is called soundscape. It combines the word sound with the morpheme -scape, which refers most directly to the word landscape. However, it carries connotations not of solidity associated with mountains and meadows that form a landscape, but rather, of a process of creation or formation. For that matter, Kay Kaufman Shelemay, speaking about her idea of soundscape (which is similar to ours and about which we will speak a little later), refers to seascape, which provides a more flexible analogy to music’s ability both to stay in place and to move in the world today, to absorb changes in its content and performance styles, and to continue to accrue new layers of meanings.1

The word soundscape was first popularized in the 1970s in the work of the Canadian composer and sound ecologist Raymond Murray Schafer and his colleagues. In their concept, a soundscape is comprised of the sound characteristics of a concrete environment, some sort of sound parallel to a landscape, including the sounds of cars, bells, footsteps and birds singing. . . Schafer and his team considered this sound landscape, the sound environment, both as a research topic (being primarily interested in people’s perceptions of it) and also as a special sort of artistic work. In this approach, they were not far from John Cage, who is discussed in the third chapter.

In 2000, the word soundscape was used by the Harvard ethnomusicologist Kay Kaufman Shelemay in the title of her book. While the form of the term itself was inspired by the cultural anthropologist Arjun Appadurai,2 in the content Shelemay followed up on the well-known three-part analytical model of the classic ethnomusicologist Alan Merriam (1964). In it, Merriam, a trained anthropologist (and passionate musician) suggested how to research music from the anthropological perspective – as a product of human activity. What we are accustomed to calling “music itself” (and what Merriam calls “sound phenomenon”) is a product of human behavior – the movement of fingers on strings, the vibration of vocal chords – and also of the interaction of the audience when it spontaneously joins the performing group e.g. by clapping in rhythm. The review of an operatic performance that the critic writes for an influential newspaper also belongs here: this “verbal behavior” can cause the soprano, Madam X., whose vibrato was criticized by the reviewer, not to sing the main role next time.

Verbal behavior also belongs in this category, whether in the form of a written review of an operatic performance or oral disagreement with the playing of a local cymbalom band at a wedding. All of this influences the sound of music now or in the future.

The above-mentioned types of human behavior, however, are not accidental; on the contrary, they are deeply rooted in human ideas, values and concepts – be they about music or, more broadly, about the world in general. The ancient Indians, convinced of the spiritual effects of sound, tried with all their might to avoid mistakes during the performance of ritual chanting. Therefore, they created the first known musical notations and established one social stratum especially for the performance of these sacred texts. And thus it is still possible to listen to their ancient (sometimes very complicated) melodies today. Musicians in a punk band, convinced of the rottenness of the majority society, express their revulsion, their rebellion, their negation in various ways: with simple crudeness against the cultivated and complicated classics, with amateurism available to everyone against specialization (including musical), and by wearing rumpled and even torn pants, socks and jackets with unfriendly and prickly-looking decorations against refined, fancy clothing.

As far as people are concerned, Merriam’s model, like the cultural and social anthropology of the time, assumed a relatively simple world of more or less isolated, homogeneous, and, moreover, static groups.3 It is exactly because of this unrealistic view that Shelemay emphasizes that dynamic similarity to the seascape which makes it possible to grasp changes in the sound world and in the world of people. We use the expression “musical world” as a synonym for soundscape for such an idea of music in the most various contexts.4

Both concepts clearly differentiate in their musical ties; while Schafer’s concept binds sounds to a place, Shelemay connects them primarily to people – to those who produce music as well as those who listen to and appreciate it. The latter concept is understandably closer to us as musical anthropologists. We also agree with Merriam’s and/or Shelemay’s understanding of music: following the ethnomusicological tradition (and perhaps somewhat limited by a tradition of historical musicology), we understand music as an intentional human creation. Concretely: we would not unequivocally agree with the classical musicological assertion that music is (only) a sound structure which bears esthetic information. We know that phenomena we would designate as music have (and, as is apparent in the music of Prague, not only in rather exotic cultures) various meanings in different cultures and in many cases it would not occur to the “users” of these phenomena to ask if the music is “lovely.” Nevertheless, we constantly oscillated between Blacking’s thesis that music is “humanly organized sound” (which we understood as “intentionally humanly organized sound”), and a newer concept, highly popularized by Christopher Small, that music is actually human activity,5 which is not too far from Merriam’s understanding.

Thus, decisive for us is the intentionality which connects sound to people. The idea of Schafer and his followers that the sound of passing trams, random footsteps and slamming doors could be perceived as art or music is alien to us, not only because we are not such limited traditionalists, but also because it is closer to the anthropological point of view of understanding music as an intentional human creation than as a product of place.

But what can we do if the concept of music, its most crucial intention, becomes unintentionality, thus the unintentionality of the resulting sound shape, and, on the contrary, the intentional connection to the random sounds of a place? That was exactly the case of a special type of concert – a “sound-specific performance” (as the organizers called it) – in the Bubeneč sewage disposal plant, which we will discuss later, and other Prague musical events. One dimension of our three-dimensional research reality – the dimension of music – gradually became foggy.

Moreover, inside the unclearly bounded phenomenon called music, there are, as we knew from our own research and that of other ethnomusicologists, very permeable borders of categories called genre or style. And, thus, what is called a mantra in two different places sounds completely different in each. Or the music sounds similar, but it means something different to those who play it and those who listen to it. Jazz could be an example: so full of meaning for the Czech youth at the very beginning of World War II (as Škvorecký writes about it), meaning so far from that of the Afro-American fathers of jazz a half century earlier. This is exactly the accruing of new layers mentioned by Shelemay.

The fogginess, related at first to the concept of music and its categories, is also applicable to the second axis of our interest: people. Like Merriam, thinking about the rather simple reality of isolated homogeneous societies, the world was viewed in the same way by many sociologists and cultural anthropologists.6 When they became interested in groups of people who differed from others (usually in an urban environment), groups that they began to call subcultures, they realized that their common element was often musical style. Sometimes musical style directly generates such groups,7 sometimes it strikingly indicates them,8 and sometimes this process is a two-way street. Punk subculture is usually mentioned as an especially famous example. Our experience – be it from the musical style itself (and thus, from the sound of the music) or from the people we met – revealed a world less “homogenized” and less clearly segmented. The majority of today’s teenagers would most likely say that they belong MORE OR LESS (and this is meant literally: sometimes more and sometimes less, sometimes only fleetingly) to one subculture or another.9

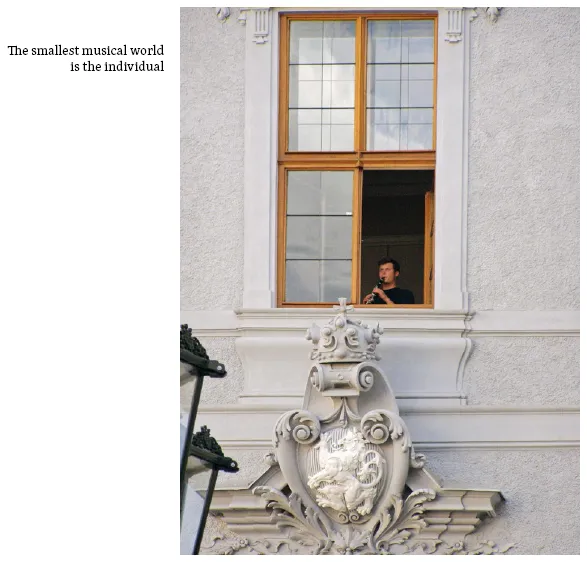

Some of today’s philosophers and sociologists agree. While in traditional societies people had, according to Anthony Giddens, a relatively fixed majority of social roles and ways to fulfil them (and thus possibilities for their own self-creation were limited), for our “late modernity” an overwhelming offer of possibilities is significant, and everyone can always chose an answer to the question, “Who am I and how shall I behave?”10 The picture of homogeneous subcultures crumbles. This approach is taken to the extreme by Mark Slobin,11 according to whom everyone is a unique musical culture. Most ethnomusicologists would rather, however, identify with Kay Shelemay, who says, We do not study a disembodied concept called “culture” or a place called “field,” but rather a stream of individuals.12 We thus perceive a human world metaphorically as a mass of individuals carried by the same stream. Some are closer to the center of the stream; some are more on the side; some get out and climb on the bank. Sometimes the stream splits or, on the contrary, merges with another one. We can apply the thesis of Zygmunt Bauman about liquid modernity,13 including that of musical worlds. Or we can use the idea of the universe with galaxies, orbits, and individual planets. The closer we look, the more detailed are the worlds which open to us, until we reach the world of each human individual.

For the understanding of such individual worlds, Timothy Rice offers a model which is similarly three-dimensional to the one we thought about at the beginning. Its axes are, however, different: time, place and metaphor.14 On the axis of time, chronological as well as historical (how a musical composition flows, in which “objective” time its performance is set), is interwoven with the phenomenological, experiential one (how I perceive it – most likely in a different way from the first time, etc.). On the axis of place, Rice leaves an idea of a concrete, “natural,” physical place (we and our subjects increasingly dwell not in a single place but in many places along a locational dimension of some sort15) and accepts the idea that it is a social construct in which a social event is set into the most varied coordinates. (Where, in my personal history, did that happen?). Here Rice comes close to the socio-geographic method of mental maps which some researchers use to try to understand how people perceive their environment.16 How would Prague look on the mental map of a techno fan and, on the other hand, of a singer of Gregorian chant?

The third dimension is metaphor. Rice uses this term to mean . . .the fundamental nature of music expressed in metaphors in the fo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Chapter 1 / Listening to the music of a city

- Chapter 2 / Music and identity

- Chapter 3 / Music and social stratification

- Chapter 4 / Music and rebellion

- Chapter 5 / Music as goods

- Chapter 6 / Electronic Dance Music

- Chapter 7 / Music and spirituality

- Summary

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Prague Soundscapes by Zuzana Jurková in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Ethnomusicology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.