![]()

Part I

ASSEMBLY DEMOCRACY

![]()

THE OPENING EPISODE OF THE HISTORY of democracy saw the birth of public assemblies – gatherings in which citizens freely debated, agreed and disagreed, and decided matters for themselves, as equals, without interference from tribal chiefs, monarchs or tyrants. Let’s call it the age of assembly democracy.

The origins of this age come shrouded in uncertainty. Some have tried to spin the story that the roots of democracy are traceable to Athens. Ancient Greece, they say, is where it all began.

The idea that democracy was made in Athens stretches back to the nineteenth century, courtesy of figures such as George Grote (1794–1871), the English banker-scholar-politician and co-founder of University College London. It tells how, once upon a time, in the tiny Mediterranean town, a new way of governing was invented. Calling it dēmokratia, by which they meant self-government, or rule (kratos) by the people (dēmos), the citizens of Athens celebrated it in songs and seasonal feasts, in stage dramas and battle victories, in monthly assemblies and processions of proud citizens sporting garlands of flowers. So passionate were they about this democracy, runs the story, that they defended it with all their might, especially when spears and swords rimmed their throats. Genius and guts earned Athens its reputation as the wellspring of democracy, as responsible for giving democracy wings, enabling it to deliver its gifts to posterity.

FROM EAST TO WEST

The Athens legend still grips the popular imagination and is repeated by scholars, journalists, politicians and pundits. But here’s the thing: it’s false.

Let’s begin with the word itself. ‘Democracy’ has no known wordsmith, but in the mid-fifth century BCE, the word dēmos appeared in Athenian inscriptions and in literary prose; perhaps it was used earlier, but few inscriptions survive before this period, and prose written between c. 460 and 430 BCE has been lost. Antiphon (c. 480–411 BCE), one of the pioneers of public oratory, mentions in his ‘On the Choreutes’ the local custom of making offerings to the goddess Dēmokratia. The historian Herodotus (c. 484–425 BCE) speaks of her. So does the military commander and Athenian political pamphleteer Xenophon (c. 430–354 BCE), who dislikes the way democracy weakens oligarchs and aristocrats. There’s also an important passage on democracy in The Suppliants, a tragedy by Aeschylus. First performed around 463 BCE and a great favourite of Athenian audiences, it reports a public meeting at which ‘the air bristled with hands, right hands held high, a full vote, democracy turning decision into law’.

So far, so simple. But there’s evidence that the d-word is much older than commentators on classical Athens have made out. We now know that its roots are minimally traceable to the Linear B script of the Mycenaeans, seven to ten centuries earlier. This late Bronze Age civilisation centred on the fortified city of Mycenae, located to the south-west of Athens, in today’s orange-and olive-growing region of Argolis. For more than 300 years, its military held sway in much of southern Greece, Crete, the Cyclades islands and parts of south-west Anatolia in western Asia. It is unclear exactly how and when the Mycenaeans began to use the two-syllable word

dāmos (or

dāmo ) to refer to a group of powerless people who once held land in common, or three-syllable words such as

dāmokoi, meaning an official who acts on behalf of the

dāmos. But it’s possible that these words, and the family of terms we use today when speaking about democracy, have origins further east – for instance, in the ancient Sumerian references to the

dumu, the children of a geographic place who share family ties and common interests.

Archaeologists have made another discovery that contradicts the Athens legend. The first models of assembly-based democracy sprang up in the lands that correspond geographically to contemporary Syria, Iraq and Iran. The custom of popular self-government was later transported eastwards, towards the Indian subcontinent where, from around 1500 BCE, assembly-based republics first appeared. As we’ll see, assemblies also travelled westwards, first to Phoenician cities such as Byblos and Sidon, then to Athens, where during the fifth century BCE it was said with swagger to be unique to the West, a sign of its superiority over the politically depraved ‘barbarism’ of the East.

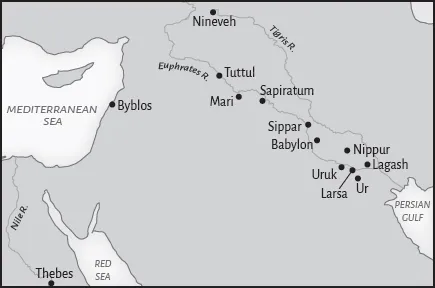

Evidence suggests that this period began around 2500 BCE, in the geographic area that’s today commonly known as the Middle East. There, public assemblies formed in the vast river basins etched from desert hills and mountains by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and their tributaries, and in the cities that sprang up for the first time in human history.

Established in areas of fertile soil and abundant water, the principal ancient cities of Syria-Mesopotamia were the cradles of self-government by assemblies between c. 3200 and 1000 BCE.

The ancient Syrian-Mesopotamian cities of Larsa, Mari, Nabada, Nippur, Tuttul, Ur, Babylon and Uruk today mostly resemble windswept heaps of grey-brown earth. But around 3200 BCE, they were centres of culture and commerce. Their imposing temples, the famous ziqqurats – often built on massive stone terraces or gigantic artificial mountains of sundried bricks – made travellers gasp with delight. Typically situated at the centre of an irrigated zone, where land was valuable, these places reaped the bounty of dramatic local increases in agricultural production. They fostered the growth of specialised artisan and administrative skills, including scribes’ use of the rectangular-ended stylus to produce wedge-shaped cuneiform writing, and they served as conduits of long-distance trade in such raw materials as copper and silver.

The cities varied in size from 40 to around 400 hectares; they felt crowded in a way our earth had never before known. Their dynamics shaped every feature of Syria-Mesopotamia, including its patterns of government. Kings are conventionally thought to have dominated this region during these centuries. But permanent conflicts and tensions – over who got how much, when and where – shaped the institution of kingship on matters such as land ownership and trade. In fact, kings of the time were not absolute monarchs – despite what later historians with Western prejudices have said. Archaeological evidence confirms that, at least 2000 years before the Athenian experiment with democracy, the power and authority of kings was restrained by popular pressure from below, through networks of institutions called ‘assemblies’. In the vernacular, they were known as ukkin in Sumerian and pŭhrum in Akkadian.

For this insight that assemblies functioned as a counterweight to kingly power, we’re indebted to the Danish scholar Thorkild Jacobsen (1904–1993). He identified what he termed a flourishing ‘primitive democracy’ throughout Syria-Mesopotamia, especially in early second millennium Babylonia and Assyria. He liked to say that, to its peoples, the region resembled a political commonwealth owned and governed by gods, who were widely believed to gather in assemblies – with the help of humans, who formed assemblies in imitation.

Was there any substance in Jacobsen’s idea of ‘primitive democracy’? There are doubts. The teleology lurking within the word ‘primitive’ – the inference that this was the first of its kind, a prototype for what was to follow – raises tricky questions about the historical connections between the assemblies of the Greek and Mesopotamian worlds. It also supposes that despite the many differences in the character and practice of democracy across time and space, there is an unbroken evolutionary chain that links assembly-based democracy and modern electoral democracy, as if the vastly different peoples of Lagash and Mari and Babylon were brothers and sisters of James Madison, Winston Churchill, Jawaharlal Nehru, Margaret Thatcher and Jacinda Ardern. There’s the risk of overstretching the word ‘democracy’ as well. If terms such as ‘primitive democracy’ (or ‘proto-democracy’, coined around the same time by the Polish-American anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski) are used too freely, we fall into the trap of characterising too many societies as ‘democratic’ just because they lack centralised institutions and accumulated monopolies of power, or because they prohibit violent oppression. Matters aren’t helped by the anachronistic use of the word with Linear B origins, ‘democracy’. And then there is the least obvious but most consequential objection: by calling the assemblies of Syria-Mesopotamian ‘primitive’, there is a danger of overlooking their originality.

But Jacobsen’s work remains important because it reminds us that the ancient assemblies of Syria-Mesopotamia are the fossils present in the ruins of Athens and other Greek democracies, and the assemblies of the later Phoenician world. These much older assemblies of Syria-Mesopotamia teach us to rethink the origins of democracy. They invite us to see that democracy of the Greek kind had Eastern roots, and that today’s democracies are indebted to the first experiments in self-government by peoples who have been, for much of history, written off as incapable of democracy in any sense. Ex oriente lux: the lamp of assembly-based democracy was first lit in the East, not the West.

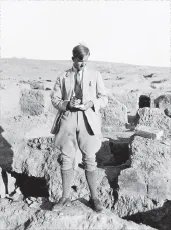

Thorkild Jacobsen in Iraq, taking notes during the clearance of a large residential quarter in the ruins of the Sumerian city Tell Asmar, c. 1931–1932.

IMITATING THE GODS

What did these assemblies look like? How did they function? Here we come across something both fascinating and puzzling. These early citizens’ assemblies were inspired by myths that gave meaning and energy to people’s everyday lives.

For the people of Syria-Mesopotamia – as for Greeks 2000 years later – the cosmos was a conflict-ridden universe manipulated by powerful forces with individual personalities. These deities had emerged from the watery chaos of primaeval time, and they were to be feared because they controlled everything: mountains, valleys, stones, stars, plants, animals, humans. Their fickleness ensured that the land was racked periodically by thunderstorms, which caused torrential rains and halted travel by turning the ground to mud. The local rivers rose unpredictably at their command, smashing barriers and inundating crops. Scorching winds smothered towns in suffocating dust at the deities’ behest.

The whole world was in motion, yet it was said that the deities had won an important victory over the powers of chaos and had worked hard to bring energy and movement into the world, to create order through dynamic integration. The resulting balance was the outcome of negotiations that took place in an assembly – a divine council that issued commands to decide the great coming events, otherwise known as destiny.

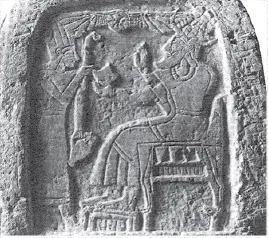

There were reckoned to be some fifty gods and goddesses, but the shots were called by an inner circle of seven. The most influential figure was Anu, the god of the sky, a rider of storms who convened the ‘ordained assembly of the great gods’. These gods were believed to have the ability to grant some of their powers to humans. Their favour could be bought. In Syria-Mesopotamia, getting a god was a means of self-empowerment. Letters were written to the gods, and festivals of wailing processions calling on them to act aroused popular interest. In every dwelling there was a shrine to the household’s chosen god, who was worshipped and presented with daily offerings. The practice of mimicking the gods’ self-governing methods was supposed to have the same effect: by emulating their capacity for oratory and collective decision-making, normally through negotiation and compromise based on public discussion, the earthly arts of self-government could flourish. So in Syria-Mesopotamia, the custom of gathering together to decide things had pagan and polytheistic roots. When citizens of various occupations and standing gathered to consider some or other matter, they thought of themselves as participating in the world of the deities, as suppliants of their benevolence.

Anu, also called An in Sumerian, was considered the divine personification of the sky, the ancestor of all ancient Mesopotamian deities and demons, and the supreme source of authority for the other gods and all earthly rulers. In at least one text, he is described as the figure ‘who contains the entire universe’.

Deep Christian and modern prejudice against this kind of mythical thinking later ensured that the ancient assemblies of Syria-Mesopotamia went unrecognised in histories of democracy. Something else played a part in this ignorance: the political economy of literacy. Writing was first used to facilitate the ever more complicated accounting that had become vital for the expanding cities and temple economies. The surviving evidence suggests that while writing enabled the birth of a significant literature in Syria-Mesopotamia, literacy was limited to elites. Recordkeeping was mostly for tracking trade and commerce, and for the administration of public institutions, such as temples and palaces, and so restricted to governmental institutions and the wealthy. This had the effect of rendering the assemblies mostly invisible to later observers. The effect was reinforced, paradoxically, by the strength of these assemblies: exactly because centralised bureaucracies such as the palace monopolised economic and administrative recordkeeping, the decentralised politics that took place in the assemblies went unrecorded – or so the evidence implies.

The old Sumerian and Akkadian words for assembly, ukkin and pŭhrum, are believed to refer, as in English, to both an informal gathering of people and a governing body. Some of them were rural. During the second millennium, for instance, tent-dwelling pastoralists from north-west Mesopotamia gathered regularly to thrash out matters of common concern. City meetings to hear disputes and issue legal judgements were commonplace. The assemblies’ mandate included the power to tread on the toes of monarchs – as noted in a political text called Advice to a Prince, a clay tablet recovered from the world’s oldest library, at Nineveh, in modern-day northern Iraq. Written in Babylon towards the end of the second millennium BCE, it warned monarchs that the gods and goddesses would not look kindly upon their meddling with the freedoms of city and country life. If a greedy prince ‘takes silver of the cit...