1. The Road to Sierra Leone

Peace is not the absence of war; it is instead the presence of justice.

—Bob’s Laws

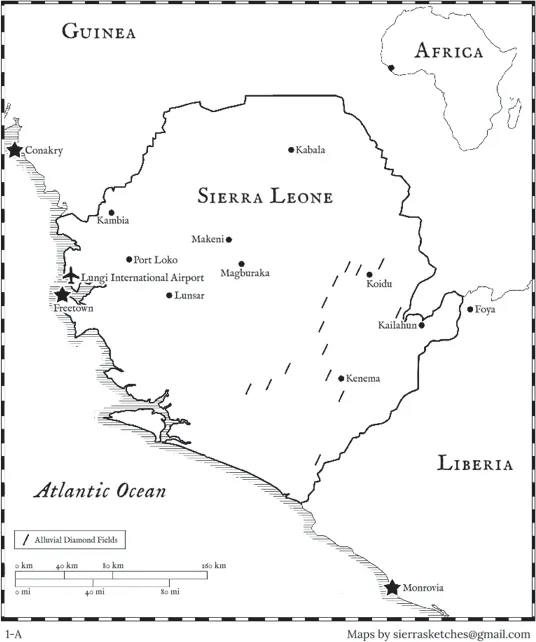

Figure 1. Map of Sierra Leone

I was an American soldier for well over two decades. Following my retirement from active military service, I was at a loss for something worthwhile to do. In retirement, I missed the meaning and purpose the military had given my life. The same is no doubt true for many old soldiers. For nearly two years I tried writing, teaching, and military contracting. None of these gave me the same feeling I had experienced in uniform. Something was missing. Although not conscious of it at that time, I ultimately sought out a second profession that provided me what I needed most.

This unlikely record of events concerns my initial period of service with the UN. It is unlikely because, looking back on my fledgling years with the organization, I find it difficult to believe it all happened, and yet it certainly did. There are simply too many credible and usually sober eyewitnesses to confirm the facts. This sometimes-tragic history involves multiple rape victims, child soldiers, blood diamonds, kidnappings, invasions, emergency evacuations, refugee camp violence, gun fights, jihadist suicide bombings, the abuse of power, institutional corruption, political expediency, and betrayal.

I never imagined that my choice of the UN might nearly result in my own death or the death of someone I loved. I was wrong.

It was 21 August 1999. I had been serving in Sarajevo for nearly a year as a defense policy advisor to the fledgling government of Bosnia-Herzegovina. My year-long contract was generated by the US State Department and performed by Military Professional Resources Incorporated, a private military contractor. Essentially, we were attempting to assist the three formerly warring factions build a national and—we hoped— unifying army in the wake of a terrible war. I drafted the Defense Planning Guidance and Army Plan. These are both keystone national-military policy documents.

The previous work year had been long and tedious, producing unquestionably questionable results. The Roman Catholic Croats, Orthodox Christian Serbs of Republika Serbska (a Serbian enclave within Bosnia) and Bosnian Muslims had demonstrated little trust in one another or the future of the international community’s cobbled-together nation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Their mistrust of one another was real and justified. Much blood had been spilled. Essentially, the country seemed to be headed nowhere.

The war in the former Yugoslavia was punctuated with war crimes. An especially heinous act was perpetrated by the Serbs when they massacred over 7,000 Muslim men and boys in 1995 at a place now infamous, Srebrenica. More than 20,000 residents of the town and environs were also “ethnically cleansed,” meaning they were either killed or forcibly driven from their homes.

Although the Serbs were clearly responsible for the tragedy, the UN also had to admit its own failings. The unfortunately named UN Protection Force proved to be unable to protect itself, much less the population of Muslims. CNN and other media outlets provided embarrassing video of UN “blue helmets” shackled to bridges by Serb forces, meant to dissuade American and allied military pilots from bombing them.

The residents of Sarajevo endured sniper fire from the ridgelines high above the city that failed to discriminate between combatants and noncombatants or women and children— killing anybody seen moving below. Not all the residents who attempted to negotiate what came to be called “Sniper Alley” survived.

Much later, after my arrival in the Balkans in the early fall of 1998, another conflict developed in an obscure province of Serbia called Kosovo—largely populated by ethnic Albanians, also Muslim—which now seemed poised to break away from Belgrade. In my spare time, I wrote a series of commentaries for the Army Times newspaper on the War in Kosovo.

My bosses at Military Professional Resources Inc. apparently found my work satisfactory. In the late summer of 1999, they offered me additional money and a twelve-month extension on my contract. The money was all right, and I enjoyed learning more about the former Yugoslavia and traveling in the region; the Balkans have a fascinating history. No matter the interest, the job could not keep me there, as one issue was unresolvable: The newly established government mandated by the international community enjoyed little popular support among the former warring parties. The tripartite presidency was utterly dysfunctional, and the assumed merger of the armed forces was anything but a reality. As of this writing, roughly eighteen years later, not much has changed. It was clear to me even back then that ending a war is one thing, but that attempting to ensure actual reconciliation was a very different objective requiring a different strategy. In other words, ending the war is not enough. The challenge of building a durable peace remains. I began looking for alternative employment.

The UN subsequently offered me a post as Chief Security Officer (CSO) for their unarmed military observer mission in Sierra Leone, West Africa. I soon accepted. From my perspective, the UN offered me more than a job. It offered me the possibility of a second act in service.

Although having previously served on UN peacekeeping missions as a soldier, I had no experience working as a member of the civil staff. My prior UN service had all been as a volunteer while on active duty in the US Army. As I was to discover later, the differences between the military and civil sides of the UN are significant.

My previous peacekeeping tours had served to introduce me to that side of the UN. I say, “that side” because the UN is multifaceted. There are political, developmental, and humanitarian functions as well. But at the front end of my UN service, peacekeeping was the primary focus.

The unarmed variety of peacekeeping is a different sort of military mission. UN member states provide officers to serve as military observers. The most common term is UNMO, short for UN Military Observer. The general mission statement is to “observe and report.” UNMOs observe the status of the peace and write reports for the gratification of the UN Security Council that establishes the mandate under which the mission operates. Essentially, unarmed UNMOs are placed on the ground between former belligerents. Their lives are then held hostage to the peace process. Although little-reported, it is not uncommon for military observers to die in the performance of their duties. I found this type of peacekeeping service, in the abstract, to be an honorable endeavor. The reality, though, was sometimes something else entirely. As a matter of historical import, approximately three thousand eight hundred peacekeepers have died in the performance of their duties around the globe.

Another type of peacekeeping involves the use of armed battalions. I had seen this permutation in 1990 while serving with UN Observer Group-Lebanon in the form of the UN Interim Forces in Lebanon, and two years later with the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia. My future mission would combine elements of both UNMOs and armed battalions.

The key assumption on the part of the UN Security Council when establishing a peacekeeping mission is that there is a genuine peace to keep. That assumption proved false in several countries. As many discovered over several decades of peacekeeping, genuine peace is often anathema to one or more parties to UN-brokered agreements, especially when such agreements are between warring factions within the same country.

The infamous 1994 genocide in Rwanda is merely one example. Majority tribal Hutus planned and executed the murders of up to one million minority tribal Tutsis, and directly under the noses of armed UN peacekeepers, who, following orders from New York, did little to stop the genocide. Although recent scholarship tends to mitigate Hutu guilt, the dead don’t care.

Then there is the issue of the UN deploying armed troops of many nations to enforce a peace between formerly warring parties. This one is a very tough nut. The UN is not a capable war-fighting organization. One of the key reasons is that the troops sent by various nation-states are often not the best the country has to offer. Sub-Saharan African countries, for example, tend to keep their best troop units at home to protect the interests of the powerful.

I entered UN civil service on 22 September 1999, two years following my retirement from the military. I was excited and pleased. Because of my previous experience in both the US Army’s Special Forces and UN peacekeeping, I felt reasonably confident that I could handle whatever challenges presented themselves. I was wrong.

My briefing officer in New York was Richard Manlove. Like me, he was a retired US Army lieutenant colonel. Our paths would cross many times in the future. In my briefing, I was informed that there was a very good chance the mission in Sierra Leone was about to get much larger, and far more complex.

I would receive no training prior to deployment. Essentially, my competence to serve as the mission’s CSO was assumed based on the résumé I had presented to those doing the hiring in New York. However, there was nothing in that résumé that reflected anything other than an extraordinarily eclectic military career. On reflection, I wish there had been some security-based instruction. My training would all be on-the-job and much of it self-taught. So at least at the start of my UN service, I was, at least in my own estimation, largely technically incompetent and stepping into an arena that would test me in unexpected ways. It proved to be an inauspicious beginning.

I arrived in Sierra Leone less than a week later from Conakry, Guinea, onboard a Soviet-era Ukrainian-contract World Food Program helicopter, and without a visa stamp on my UN blue Laissez-Passer (UN Passport). The fledgling government had not yet quite gotten on its feet sufficiently to manage its borders properly. We landed at what passed for a helipad. I was accompanied by several UN staffers, as well as the new Regional Security Officer for the US Embassy in Freetown. I was tired. The trip from New York had been a long one.

Riding in Soviet-era helicopters is always an adventure. Two of them fell from the sky while I was serving in Cambodia. Although their pilots were first-rate (many had served in the Soviet Union’s ill-fated Afghan War), their helicopter maintenance was questionable. Also, there was the issue of alcohol consumption. Soviet-era pilots and their crews seemed to love vodka, even when flying. In general, I prefer my pilots sober.

In addition, Soviet whirly-birds of this vintage tended to shake. They shake on takeoff. They shake at cruising altitude. They shake upon landing. It always seemed to me that when the blades were turning, they were just moments away from shaking apart, not like American-made helicopters at all. I always took safety procedures very seriously when flying in these aircraft. Luckily, and after what seemed a very long ride, I sighted Freetown Harbor from one of the port-side windows. Still, I did not relax completely until we returned to Mother Earth. Fortunately, the landing was uneventful.

The helicopter’s back ramp lowered slowly to the attendant scream of hydraulics. Shirtless black men entered by the ramp and began wordlessly unloading cargo. The sky was overcast; it had rained earlier, and the late-afternoon air was cool. The passengers debarked by the port-side drop-stairs. UN agency vehicles were there to collect their staff. I was supposed to have been met by the incumbent CSO, but there was nobody there to greet me.

The new American Embassy ...