![]()

1

Family and Early Years, 1889–1911

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) was born and grew up in Vienna. It is not surprising that one of the most important philosophers in the modern age originated from this fabled metropolis. In the last decades before the First World War, Vienna was at the height of its imperial splendour, the capital of a vast and heterogeneous empire. It was one of the main cultural centres of the world, a melting pot of pathbreaking artistic and intellectual currents, a place where the stiffest conservatism clashed with the most radical modernism, where the demise of the old world and the hope for a new beginning were sensed most vividly, a place rife with contradictions, obsessions and genius. Sigmund Freud developed psychoanalysis in Vienna, Arnold Schönberg atonal music, Adolf Loos functionalist architecture, Gustav Klimt Secessionism, Arthur Schnitzler his taboo-breaking theatre and Karl Kraus his apocalyptic satire, to name but a few.1 It was also a place of political ‘innovation’, if we are to count not only Theodor Herzl’s Zionism and Victor Adler’s and Otto Bauer’s versions of socialism, but also the populist exploitation of anti-Semitism by the mayor Karl Lueger and the formation of Adolf Hitler’s ideology during his Viennese apprenticeship years. Some of the most remarkable but also darker aspects of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s personality can be traced back to this fin-de-siècle world, its refined sense of culture, its strict sense of duty, its cult of genius and tragedy, its awareness of a world in disintegration, and maybe to its sexual repression and anti-Semitism.

The Wittgenstein family’s ancestors were Jewish. Ludwig’s paternal great-grandfather, Moses Maier, lived in county Wittgenstein in Germany, now part of North Rhine–Westphalia, and was a land agent to the princely family Sayn-Wittgenstein. The family did not have aristocratic roots, although this was rumoured at times. Rather, Moses Maier took over the name ‘Wittgenstein’ following Napoleon’s decree that all Jews must adopt a surname. What is certain is that Moses’s son and Ludwig’s grandfather, Hermann Christian Wittgenstein (1802–1878), converted to Protestantism, cut off his ties with the local Jewish community and moved to Leipzig, where he became a successful wool merchant. He was described as stiff and irascible, but also as determined and very religious, viewing life as a calling to self-accomplishment. In 1838 he married Fanny Figdor (1814–1890), the daughter of a rich, highly cultivated Viennese family, who, like him, renounced her Jewish faith and converted. The break with Judaism seems to have been so complete that Hermann Christian forbade his children to marry Jews. Indeed, he seems even to have been known as an anti-Semite, a state of mind that was not rare among converted Jews at the time. When they moved from Leipzig to Vienna in the 1850s the Wittgensteins did not participate in the Jewish community, but gave their children a thorough Germanic education. Through Fanny’s family the Wittgensteins maintained close connections to the Viennese cultural and artistic elite. They were known as art collectors and as patrons of music. The famous violinist Joseph Joachim was adopted by Fanny and Hermann at a young age and sent to Leipzig to study with Felix Mendelssohn. Johannes Brahms was among numerous famous friends, giving piano lessons to the Wittgenstein daughters. The playwrights Franz Grillparzer and Christian Friedrich Hebbel were two other such illustrious friends. This privileged education and cultural exposure contrasted with the otherwise frugal regime that the children were deliberately brought up in.

The Wittgenstein family house, the ‘Palais Wittgenstein’ in Vienna.

Out of the ten children of the couple, Karl (1847–1913), Ludwig’s father, was the most remarkable. He was rebellious, highly intelligent, good-looking, self-confident, impatient (especially with things he considered a waste of time, such as philosophy), at times frightening. In her unpublished memoirs his daughter Margarete writes that she had almost only sombre memories about her childhood. ‘I did not deem the often irradiating gaiety of my father funny, but frightening.’2 Karl was also practically minded and determined to make his own way – if necessary, against his father’s or anybody else’s wishes. As a teenager he ran away from home twice, the second time just after he had been expelled from school for denying the immortality of the soul in an essay. He ended up in New York, where he worked as a waiter, violinist and teacher of music, mathematics and other subjects, finally returning home after two years with some money earned by himself and an invaluable experience of the New World. In later years he repeatedly praised the free market system in newspaper articles, while the Socialist press criticized his aggressive business methods, denouncing him as an ‘American’. He studied engineering and worked first as a draughtsman in the railways, then in the construction of ships and turbines. At 27 he was the managing director of a Viennese company and from then it took him only two decades to become a steel magnate, heading several companies and turning into one of the wealthiest industrialists in Europe, much like Andrew Carnegie in America, whom he in fact befriended. Indeed, the family had the byname the ‘Carnegies’ of Central Europe before the war. At the age of 52 Karl Wittgenstein suddenly retired from business and transferred most of his fortune into us equities, which would make his family even richer with the onset of the economic depression following the First World War, and devoted his time to his family, to art and to writing sharp-witted political and economic articles for various periodicals. Although he refused the offer of being ennobled by adding a ‘von’ to his name (as this would have betrayed the parvenu), he lived in Vienna with his family in an aristocratic mansion, known as ‘Palais Wittgenstein’, built in the nineteenth century by a Hungarian count, and also possessed a house in Neuwaldegg on the outskirts of the capital, where Ludwig was born. In the summer the family would retreat to the Hochreit, Karl’s country estate and hunting lodge in the mountains. As a patron of the arts he showed sensitivity for innovative developments, funding, for instance, the famous Sezession building, befriending the first president of the Vienna Secession group, Gustav Klimt, and generally surrounding himself and his family with the crème de la crème of the Viennese elite. ‘The minister of fine art’, as Klimt called Karl, acquired a large collection of art pieces, by Klimt himself, by Rodin, Max Klinger and others. Besides the grand old man Brahms, musicians such as Bruno Walter, Clara Schumann, Gustav Mahler, Josef Labor and Pablo Casals were also close to the family.

Wittgenstein’s parents. His father was a leading industrialist, his mother an accomplished pianist.

Karl had eight children with his wife Leopoldine Kalmus (1850–1926), whose parents both came from prominent Catholic families. Her father, however, had Jewish ancestors and so three of Ludwig’s grandparents had Jewish ancestry. In conformity with their mother’s denomination, Ludwig and his siblings were baptized into the Catholic faith, but there seems to have been little churchgoing in the family. Although fully devoted, indeed subservient to her husband, Leopoldine’s relations with her children were not the warmest and they were, typically for a family of this social status, surrounded by nursemaids and private teachers most of the time. But there was one exception to this, and that was music. Leopoldine was an extremely gifted pianist and devoted much time to the musical education of her children. She was also a merciless critic. Often after a concert of the Vienna Philharmonic a large circle of music experts would gather in the Palais Wittgenstein and analyse the performance, with Leopoldine dominating such occasions, perhaps not unlike Ludwig many years later in Cambridge’s philosophy circles. She was considered such a good pianist that some liked her playing better than that of her son Paul, the celebrated concert pianist. Most of her children were musically very talented and active, but her two sons Hans and Paul were exceptional. Hans was a pianist of genius, who gave public performances even as a child.

A story [Ludwig] told in later life concerned an occasion when he was woken at three in the morning by the sound of a piano. He went downstairs to find Hans performing one of his own compositions. Hans’s concentration was manic. He was sweating, totally absorbed, and completely oblivious of Ludwig’s presence. The image remained for Ludwig a paradigm for what it was like to be possessed of genius.3

But his father was unmoved by this talent and had decided that his son should follow a business career. The conflict between the duty felt towards his father and his own calling caused severe tensions in Hans. Eventually, he ran away from home and ended up in the United States. He vanished from a boat at the age of 26 in Chesapeake Bay, an event that was interpreted as suicide.

Of Karl’s five sons, two more, Rudolf and Kurt, committed suicide and Ludwig too would contemplate suicide throughout his life. Such events suggest that, despite all its cultural sophistication, there was something tragic, ruptured and morbid about this family, a good illustration of the thesis Tiefenpsychologie that Freud developed in Vienna, not by coincidence. As Brian McGuinness once put it, the family history ‘contains many anecdotes that may have figured in the appendices to a treatise on psycho-analysis’.4 Rudolf, whose greatest interests were literature and theatre, was psychologically unstable. He suffered from the thought that he was a homosexual (a ‘perverted disposition’, as he described it in his farewell letter) and when he seemed to be unable to cope with his life in Berlin he ended it. He walked into a pub, ordered drinks, asked the pianist to play the song ‘I am lost’ and poisoned himself on the spot. He too had come into conflict with his father’s expectations. Although the same is not true of Kurt, who killed himself because his soldiers deserted him while he was serving as an officer in the army on the Italian front in 1918, all these suicides betray an almost unbearable sense of duty, be it towards themselves or towards the overpowering father figure – a sense of duty that would sooner or later crush them.

Wittgenstein with his brother Paul and sisters.

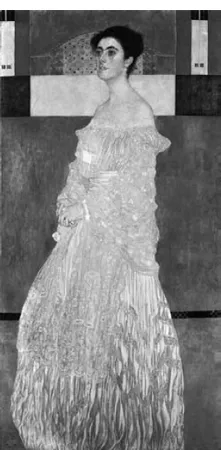

Since the daughters did not experience the same kind of pressure from their father, their lives followed a more balanced pattern. Hermine organized musical evenings, helped her father in acquiring his extensive picture collection and writing his autobiography, and later managed a day-care centre for children. She wrote a book about the family (Recollections) that contains insightful portraits and numerous fascinating anecdotes. She never married, but was considered the most harmonious person in the family. Helene did marry. She had great musical talents, but did not use them professionally. She also had a sense of humour that Ludwig could relate to, since she liked to play nonsensical games with language, which led to many funny exchanges with her philosopher brother, who was later to say that one could write a good philosophical book consisting entirely of jokes. But his closest affinity was with his youngest sister, Margarete (‘Gretl’), a beautiful woman with a strong personality, sharp, critical intellect, a predilection for artistic innovation and passion for new ideas such as psychoanalysis. She was to become a friend of Sigmund Freud, who psychoanalysed her and whom she helped to flee the Nazis. Margarete exercised a great intellectual and artistic influence on her brother Ludwig. As Hermine wrote about her:

Gustav Klimt, Margarete Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, oil on canvas. Margarete was one of Wittgenstein’s sisters.

Already in her youth her room was the embodied rebellion against anything traditional and the opposite of a typical young woman’s room, as mine was for a long time. God knows where she found all those interesting objects with which she decorated her room. She was brimming with ideas and, most important, she could achieve what she wanted and she knew what she wanted.5

She married a wealthy American in 1905, Jerome Stonborough, and Klimt was commissioned to draw her wedding portrait, a painting that is now one of his most famous.

As a result of the tragic deaths of Hans and Rudolf, the younger sons Paul and Ludwig were treated differently. Paul, two years older than Ludwig, received a classical education and was allowed to pursue a career as a concert pianist and piano teacher. This career was tragically blighted when he lost his right arm in the First World War. Nevertheless, having a strong will, like so many of his relatives, he did not give up and learned to play with his left hand alone. He even commissioned special works from composers such as Richard Strauss, Sergej Prokofiev, Benjamin Britten and especially Maurice Ravel, who wrote the famous Concerto for the Left Hand (1932) for Paul. Here is what Ludwig told Maurice Drury about Paul in 1935:

[Wittgenstein] said that his brother had the most amazing knowledge of music. On one occasion some friends played a few bars of music from any one of a number of composers, from widely different periods, and his brother was able without a mistake to say who the composer was and from which work it was taken. On the other hand he did not like his brother’s interpretation of music. Once when his brother was p...