- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Dirty theory follows the dirt of material and conceptual relations from the midst of complex milieus. It messes with mixed disciplines, showing up in ethnography, in geography, in philosophy, and discovering a suitable habitat in architecture, design and the creative arts. Dirty theory disrupts a comfortable status quo, including our everyday modes of inhabitation and our habits of thinking. This small book argues that we must work with the dirt to develop an ethics of care and mainte- nance for our precarious environment-worlds.

Information

Chapter 1

A Dirty, Smudged

Background

Background

The primary reader on dirt, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, which was first published in 1966, was bequeathed to us by the ethnographer Mary Douglas. That this is the work of an ethnographer should be a reminder that in pursuit of an adequate approach, we must remain close to the ground, listening, not being quick to make assumptions, not judging pre-emptively. Ben Campkin and Rosie Cox, who dedicated their edited collection Dirt: New Geographies of Cleanliness and Contamination (2007) to Douglas, subsequently address this material-concept, dirt, from the point of view of geography, thereby expanding social considerations of dirt in order to address its spatial qualities. Dirt, they explain, “slips easily between concept, matter, experience and metaphor” (1). It gets into the gaps, troubling the distinctions by which we attempt to order and control a world. Campkin and Cox’s project aims to update theories of dirt with an emphasis on their spatial implications, and as a means of analysing societies and spaces in their complex relations to dirt.

Plotting a theory of dirt inevitably means passing through the work of Douglas, and paying respects to other dirty theorists on the way. It is, for instance, in the shade of STS (Science Technology Studies), feminist new materialism, and the feminist posthumanities together with the emergence of the environmental humanities, that the importance of dirt becomes even more pressing, reminding us as it does of the material stuff and relations of our environmental milieus. In this way, dirt alerts us to our situated positions and what Peg Rawes calls “relational architectural ecologies” (2013). Architecture, design and art, the creative disciplines generally, those disciplines embroiled in ethico-aesthetic concerns, inherently establish an attitude to dirt. All those processual practices in which we think stuff though drawing and modelling it, where we think through doing, making a mess in order to understand the implications of the role we play in world-making, need to engage a thinking-doing with dirt.

From her perspective as ethnographer, Douglas argues that by tracking dirt we can gain an understanding of the interconnections and patterning of a world (1966, vii). In her structuralist framework, as she explains it, a desire to purify inevitably alludes to a larger whole, a system, and the dirt you discover must be located, situated and understood from amidst myriad emergent connections and disconnections. Douglas observes that if “uncleanliness is matter out of place, we must approach it through order” (1966, 41), and if we are to understand contexts other than our own, she advocates that we should also be able to critique our own habits, rituals, assumptions and norms. Removing the dirt reveals the pattern, presumably produced by the norm, that orders subjects, spaces and societies. Without dirt, though, how could patterns and creative processes of ordering be activated in the first place? This is not to say that dirt comes first, but it certainly draws attention to the interdependency of dirt and acts of cleaning – what Haraway, Barad and their companion thinkers would call “entanglements”. Acts of cleansing and acts of cleaning. Surely a distinction must be made, for such acts can lead to violent erasures or creative possibilities in the forging of new relations.

On returning to Douglas’s seminal work, Campkin argues that we must take her oft-cited formula “dirt is matter out of place” not as something fixed, but rather as something ambiguous. He warns of universalisation and of the tendency for readers to get stuck on Douglas’s formula, understanding it as a binary, when in fact it opens up the deeply ambivalent qualities of dirt. Not all matter out of place is dirt, and dirt certainly has a place, as he remarks, in terms of our systems of organisation of societies and worlds. Dirt, filth, abject stuff can all be both a dangerous pollutant and something valuable, even incorporated into sacred rituals, as Douglas demonstrates. Dirt is contradictory, complicated and restless. We must attend to dirt on a case-by-case basis, accepting its situated contingencies. When we locate what we would define as dirt or dirty, it can be discovered in places where it would appear to belong: in the rubbish bin, the waste dump, the sewage plant, spaces of ablution. (As a friend recently pointed out to me, when my baby shits in its diaper, for sure the shit is dirty, but it belongs there; it is only when the diaper leaks that the shit becomes dirt, matter out of place.) There is the emergence of dirt, the event of dirt taking place at the moment of failure – the temporal aspect of dirt. Ablutions must be continually cleaned away; the waste dump will reach maximum capacity, and so on. As quick as the will to catalogue and classify dirt may be, the emergence of new forms of dirt is quicker. The long list of dirty things, by which an attempt is made to order dirt, is unending, its composition demanding a conceptual labour that would be perpetual.

Dirt confronts us with the radical contingencies of experience, and yet this is not to say that such a confrontation should be abysmal. When we dig deeper into Douglas’s Purity and Danger, in fact we find that the formula is derived from the work of the pragmatist philosopher William James. Douglas explains this, quoting James at length in a passage that concludes as follows: “Here we have the interesting notion… of there being elements of the universe which may make no rational whole in conjunction with the other elements, and which, from the point of view of any system which those elements make up, can only be considered so much irrelevance and accident – so much ‘dirt’ as it were, and matter out of place” (William James cited in Douglas 1966, 165). That which disrupts systems and threatens the infrastructures that support everyday life, which undoes social relations and causes political unrest, which lacks sense or threatens a milieu (social or otherwise) with nonsense, irrelevance and accident, belongs in the category that James defines as “dirt”, held in the containment of his inverted commas.

James is a thinker that Deleuze and Guattari have drawn upon in establishing their ethics of difference, specifically borrowing James’ concept of a radical empiricism. What is a radical empiricism? It is an onto-epistemological position that situates all life as unfurling in a state of continuous flux from which identities and states of affairs emerge, and into which they dissipate. In the midst of this field of immanence that is life, the subject-environment assemblage persists as “a habitus, a habit, nothing but a habit in a field of immanence the habit of saying I” (Deleuze & Guattari 1994, 48). Sheltered here is a message concerning the profound imbrication of subjectivities in formation and dissolution amidst environment-worlds, one bound up with the other in reciprocal relay. As will become evident in the small chapter below dedicated to dirt and differentiation, Douglas and Deleuze can be placed in dialogue around the question of dirt and an ethics of difference, that is, the complex conjunctive and disjunctive entanglements of subjectivities, environment-worlds and things. Importantly, when we frame this discussion around the subject matter dirt, we find that the contingencies of a radical empiricism, less than creating out-and-out chaos rather diversify situations and points of view in a pluralistic way, so that from the seething flux of existence, creative forms of life may yet emerge. It is out of the chaos, furthermore, that novel concepts clamour for existence. To demonstrate such complex concepts and harried relations, a sited example may be of use, and Peg Rawes can poetically lead the way.

In her edited collection Relational Architectural Ecologies (2013), Rawes opens her own chapter by inviting us to bear witness to a landscape vista. Across a field of wheat gently swaying in the breeze a woman walks. She makes her way with quiet purpose. The artist Agnes Denes and her team undertake the labour of care of planting a wheat field on the site of a former waste dump, Battery Park, in New York, and the project in question is called Wheat Field: Confrontation (1982). The iconic image that is disseminated of the work depicts Denes walking calmly with a stick through the wheat field, and in sharp contrast rising up in the background are the skyscrapers of New York. The confrontation alluded to in the title operates in a number of ways: wheat field juxtaposed with dense, energy-hungry and waste-producing urban context; former trash heap remediated as wheat field; food crises contrasted with greed and wealth, the financial capital of Wall Street just a block away. As Rawes argues, at work in this demonstrative performance and its contribution to a women’s environmental movement in art are social, material and technological systems intertwined in durational flux across what could be called a field of immanence (2013, 44). From the dirt of the massive waste dump of Battery Park, the remedial promise of a wheat field blooms, and with the dirty smudged background of advanced capitalism looming in the background such ecological relations exude a dirty resilience, though they continue to be threatened. The confrontations themselves yield transformations, both constructive and destructive. At work are the complex relational ecologies of human and non-human subjectivities and environment-worlds. The wheat field sprouts as a moment of interference in the otherwise smooth operations of Integrated World Capitalism.

Chapter 2

Dirt, Noise and

Nonsense

Nonsense

Noise is the source of all creativity. We hear this in the murmurings of both Michel Serres (2007) and Gregory Bateson (2000). Noise is nonsense, nonsense threatens disorder. From disorder emerges the compulsion to make some kind of sense, however scant and provisional. Dirt is matter out of place, that is, stuff in a state of disorganisation: “Reflection on dirt involves reflection on the relation of order to disorder, being to non-being, form to formlessness, life to death” (Douglas 1966, 5). There are both cosmic and social pollutants, Douglas observes (74). Operating in complex interconnection, there is more and there is less mundane dirt. There is dirt that is symbolically assigned, and there is dirt that we don’t always clean up after ourselves. Between the symbolic, the semiotic and the material there are relations that cohere, get sticky, leave behind marks and stains. This sticky relationality of the material semiotic likewise pertains to the relay between sense and nonsense, between the communicated message and what is too readily discounted as noise. It also pertains to the fruitful relay that travels like a shuttle between theories and practices, an animated, ever-mobile relay that the dirty theorists presented in this small book subscribe to.

In Sense of the World, Jean-Luc Nancy offers a small etymological dance around two key terms, the world and the unclean, observing that le monde (the world), can be associated with immonde (unclean). He speaks of a world heavy with suffering, disarray and revolt (Nancy 1997, 9). It might be worth hesitating in order to ask, though, what is the worth of this clever word play unless our feet get dirty while doing the dance? It has to matter, the textual play must lead somewhere, toward some shift in our practices, some recognition of the significance of our worldly ecological relations. Surely, there must be something grounded at stake? The sense of the world is unclean, which is to say, it is smudged and obscure, not clear and distinct. Clarity can be extremely dangerous. Clarity can have the stink of death about it, for it allows no compromise, no alternative visions, however indistinct and unsure. The sense of the world works in partnership with the nonsense of the world. Sense and nonsense, Deleuze observes when he follows the adventures of Lewis Carroll’s Alice, are like the reverse and right sides of a single cloth, mixing sensations of bodies with trajectories of sense (1990). At the near intersecting, asymptotic trajectories of sense and nonsense events erupt, and something (rather than nothing) takes place.

Returning to Douglas and James’s formula, noise and nonsense can be defined as information in the wrong place. There are grave dangers and risks here. A fake fact is information ‘out of place’, but implanted in such a way as to produce dire contaminations to collective modes of thinking together. Fake facts are intimately intertwined with the ideas we pass back and forth like dirty coins, and the practices these ideas are embedded in; they participate in the establishment of the normative frameworks that constrain our thinking and doing, transforming our enunciations into mere platitudes. The insidious side effects of fake facts in architecture (as elsewhere), in our troubling era of alternative truths, get us stuck in the rut of thinking-practising dogmatically. How do we develop adequate critical weapons to think-practise otherwise?

Data management plans, privacy, the eruption of fake facts and alternative truths, all cluster the 21st-Century media-sphere with so much chatter. What is spam, what is junk mail? The message we would otherwise refuse that has arrived in our inboxes to become informational refuse. Sometimes the message gets lost in the junk folder, even though it was news that we in fact wanted to hear. We should not make the mistake of believing that this is merely so much immaterial junk, for it pollutes the delimited spaces in which we are still allowed to think. The sending of empty messages back and forth requires massive material infrastructures. As my colleague Adrià explained to me, every Google search consumes energy and produces pollution as a result.

Sense and nonsense alert us to the sense-making use of concepts, which when managed confusedly can lead to obscurantisms and the bad reputation of theory work. Bad nonsense, good nonsense, nonsense that closes down, nonsense that opens up new modes of sense. Concepts are dirty because they have been handed around – they are pre-used and prepared for recycling and up-cycling. Take a concept, make it dirtier than it was in the first place. Even seemingly novel concepts admit some genealogy, they don’t arrive from nowhere. All concepts are smudged with the dirt of many hands, and a good number of etymological messes. Noise is the interference pattern that turns the message into garbled nonsense, and yet deep inside the nonsense, new modes of marvellous sense-making emerge. Dirty ditties that pack a punch re-orientate our ways of seeing, feeling, thinking and acting. Beginning in a homophonic transfer from noise to noisome, that which is noisome is defined as noxious, harmful to health, disgusting, insalubrious or unwholesome. Not whole neither. In being not whole, more construction is required, more thinking aroused. The stench might just lead you somewhere.

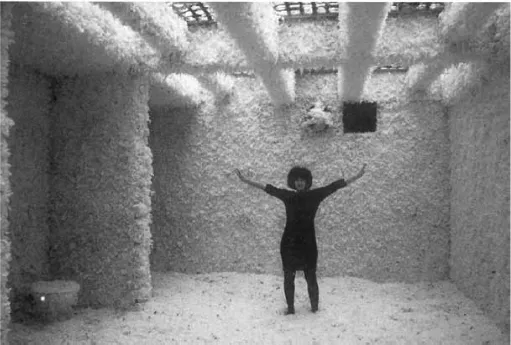

Fig. 2 Katherine Shonfield, Dirt is Matter Out of Place, 1993. View of Feathered Interior, Commercial Street, London. Photograph by Frank O’Sullivan.

An image of a woman in a public lavatory. She flings out her arms, ta da! A demonstrative gesture for a provocative project. The walls, the floor, the ceiling of her enclosure, lit from above, are (almost, not quite) entirely covered with white goose feathers. No doubt the distinct, wet smell of ablutions still invades nostrils during this brief feathery sojourn. The white feathers of a great many gooses get in the way of the reading of the hygienic lines of a public lavatory, as Katherine Shonfield gloriously demonstrates in her ephemeral architectural experiments. Shonfield is particularly fascinated in Douglas’s description of a “sea of formlessness” (2001, 36) holding perhaps too firmly onto the form and formless divide, a topical theme in the 1990s (Bois and Krauss 1997). Yet soon enough the “sea of formlessness” begins to exude its material affects, and the form/formlessness distinction gives way to the durational passage of a material, sensory mess. Are the goose feathers, seemingly pure and immaterial in their initial whiteness, the noise that obscures the ablutions of a public lavatory? Or is it that with the slow rot of the goose feathers and their associated animal stench, even representations of purity are shown to be apt to decay? Symbolic ideas of purity can abruptly transmogrify into materialisations that arouse disgust.

To address dirt alongside noise and nonsense directs us towards the sensations of assemblages of bodies, and eventually to an underground 19th-Century lavatory on Commercial Street London, originally designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor. Shonfield explains that after some time, the slowly putrefying feathers that clad this lavatory certainly did indeed begin to stink. White on white belied by incipient stink. Getting so many bags of feathers to stick, only the thickest white wallpaper paste worked, she explains, giving us the dirty details (2001, 42). Offering a brief affective description of the interior of the London Feather Company where her goose feathers were sourced, Shonfield describes how: “The underlying smell of suppressed animal, like shit partially masked by lavatory cleaner, pervades” (2001, 42). The lavatory as facility, as infrastructure, is dramatised by Shonfield according to eras: 1. The Pre-Lavatorial Era; 2, The Evangelical Era; 3. The Era of Regulation and the Division of Labour, and so on, almost as though a geology or natural history lesson were being given. The historical progression, into which the installation is inserted as moment of feathery resistance, concludes, unsurprisingly, in the era of deregulation. These are lessons that wilfully mix nature and culture, revealing in the process the dirty beginnings of gentrification by means of which the lavatory subsequently becomes an elegant neighbourhood wine bar. Filth finally bleached and scrubbed and washed out, so we can sniff the terroir of the juice of the grape.

In Shonfield’s discussion, her temporary, experimental projects are foregrounded, while the theoretical discoveries unfold later as she follows the implications of her material compositions. She expl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Introduction – Dirty Theory: Troubling Architecture

- 1. A Dirty, Smudged Background

- 2. Dirt, Noise and Nonsense

- 3. The Dangers of Purification

- 4. Dirt and Maintenance

- 5. Dirty Money

- 6. Dirty Ditties

- 7. Theory Slut

- 8. Dirty Drawings, Dirty Models

- 9. Dirt and Differentiation

- 10. Dirt Ball

- 11. Dirt and Colonisation

- Conclusion: Creative Dirt

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Copyright

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dirty Theory by Hélène Frichot in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.