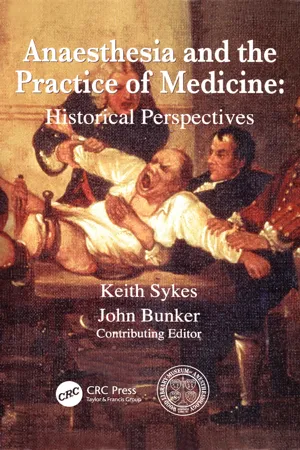

Anaesthesia and the Practice of Medicine: Historical Perspectives

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Anaesthesia and the Practice of Medicine: Historical Perspectives

About This Book

Written by two anaesthetists, one British and one American, this unique book focuses on the transatlantic story of anaesthesia. The authors have both worked at the two hospitals where the first general anaesthetics for surgery were given in 1846, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts and University College Hospital, London. Each with more than fifty years' experience of working in anaesthesia, they combine their knowledge and expertise to offer a fresh outlook on the development of anaesthesia through the ages. This highly informative and intriguing text details the origins of anaesthesia, outlines the different techniques of anaesthesia and traces its progress with illuminating and enlightening commentaries. This is a fascinating book which considers the role key figures have played in developing anaesthesia including, Queen Victoria, William Morris, La Condamine, Bjorn Ibsen and Henry Beecher. Broken down into four sections, which are divided into easy-to-read chapters and filled withtop qualityphotographs, this book makes compelling reading. It is recommended toall those interested inthe history and development of medicine through the ages, and is of particular interest to anaesthetists. More than just the science of anaesthesia, this is the story about the people and personalities who have made anaesthesia what it is today.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Part 1

Anaesthesia: The first 100 years

‘The changes that the discovery has wrought in the personality of the surgeon, in his bearing, in his methods, and in his capabilities are as wondrous as the discovery itself. The operator is undisturbed by the harass of alarms and the misery of giving pain. He can afford to be leisurely without fear of being regarded as timorous. To the older surgeon every tick of the clock upon the wall was a mandate for haste, every groan of the patient a call for hurried action, and he alone did best who had the quickest fingers and the hardest heart. Time now counts for little, and success is no longer to be measured by the beatings of a watch. The mask of the anaesthetist has blotted out the anguished face of the patient, and the horror of a vivisection on a fellow-man has passed away. Thus it happens that the surgeon has gained dignity, calmness, confidence, and, not least of all, the gentle hand.Anaesthetics have, moreover, greatly extended the domain of surgery by rendering possible operations which before could only have been dreamt about, and by allowing elaborate measures to be carried out step by step.The introduction of anaesthetics has not only developed surgery, but it has engendered surgeons. It has opened up the craft to many, for in the pre-anaesthetic days the qualities required for success in operating were qualities to be expected only in the few.’(Treves F. Address in surgery: the surgeon in the nineteenth century. British Medical Journal 1900;ii:284–9)

1 | In the beginning |

Surgery before anaesthesia

‘Yet, when the dreadful steel was plunged into my breast – cutting through veins–arteries–flesh–nerves – I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision – & I almost marvel that it rings not in my ears still! so excruciating was the agony. When the wound was made & the instrument was withdrawn, the pain seemed undiminished, for the air that suddenly rushed into those delicate parts felt like a mass of minute but sharp and forked poinards, that were tearing the edges of the wound, – but when again I felt the instrument – describing a curve – cutting against the grain, if I may so say, while the flesh resisted in a manner so forcible as to oppose & tire the hand of the operator, who was forced to change from the right hand to the left – then, indeed, I thought I must have expired, I attempted no more to open my eyes, they felt as if hermetically shut, & so firmly closed, that the Eyelids seemed indented into the Cheeks’.1

Pneumatic medicine

‘As nitrous oxide in its extensive operation appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no great effusion of blood takes place’.5

‘What is surprising is that his suggestion was ignored by the very people whom it should have interested most: that surgeons should have continued for nearly fifty years longer to operate on screaming, struggling patients in full consciousness. Surely a lasting testimonial to their thickheadedness’.6

The first attempt to produce pain-free surgery: Henry Hill Hickman

‘I feel perfectly satisfied that any surgical operation might be performed with quite as much safety upon a subject in an insensible state as in a sensible state, and that a patient might be kept with perfect safety long enough in an insensible state, for the performance of the most tedious operation. . . . I believe that there are few, if any Surgeons, who could not operate more skilfully when they were conscious they were not inflicting pain’.7

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Biographical notes

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1: Anaesthesia: the first 100 years

- Part 2: Professionalism in anaesthesia: the reluctant universities and the Second World War

- Part 3: New horizons: the scientific background of anaesthesia and the emergence of intensive care

- Part 4: The relief of pain in childbirth and the care of the newborn

- Part 5: Anaesthesia yesterday, today and tomorrow

- Index