![]()

I Chenla the Rich: Land, People, History

‘Most expensive fish ponds in the world’, Roger said. He gestured with his chin through the window of the Antonov, now cruising noisily at about 15,000 feet. From the seat behind him I looked down. The light was failing, but a little to the side of the flight path I could see clusters of round ponds, filled with pale muddy water, embedded in the landscape. They lay splattered in a crooked line over the more ordered pattern of rice-fields.

We had just left Vietnamese airspace, en route from Tan Son Nhut to Pochentong. August, the height of the rainy season, sheets of water glistening dully all the way to the horizon. The Mekong still some twenty miles to the southwest, the Delta now behind us. This was my first sight of Cambodia, in the company of a United Nations delegation with Cambodian security, and we were not particularly welcome. My neighbour, whose revolver was tucked into his waistband, was nudging my elbow; he was the Deputy Chief of Protocol. We made small talk in French, but the atmosphere on board was a little strained.

The fish ponds, now disappearing from view under the aircraft, were indeed costly imports, having been provided by the United States Air Force. The matériel alone was well over a $1,000 dollars apiece, being an M117 750-pound bomb, of which a B-52 carried about 90 on an average mission.

These 750-pounders were the workhorses of the Air Force’s war effort. Nothing smart about these bombs – just 600 pounds of Composition B, the general-purpose explosive costed at a dollar a pound, packed into a 150-pound casing. Then there was the delivery cost, from Guam. You might also want to factor in pilot training and ground control, although the value of this was moot when, as happened, and probably here, the payload was dropped in the wrong place. The earth shook, some buffaloes and farmers were blown to bits, and there you had it – instant fish ponds. The craters had no other use.

B-52 payloads were dropped from 30,000 feet in patterns known as ‘boxes’, covering an area on the ground approximately half a mile wide and two miles long. Being caught in this, whether as the enemy or as a villager on the way to a wedding, was to be ‘boxed’. The very first to fall on Cambodia had been to our right, some 60 miles to the northeast, on an area known to the Americans as Base Area 353. In the early morning of 18 April 1969, to be precise. They had triggered the whole sorry mess of Cambodia’s most recent unravelling.

An hour earlier it had not looked so likely that we would be flying at all. It was August, 1989, and the day had started well, in Bangkok, where we had assembled at Don Muang airport, a dozen journalists, under the guidance of our man from the Vietnamese embassy. Almost every morning for ten days I had taken a taxi to the Vietnamese embassy to see Second Secretary Nguyen Van Quan in an increasingly frustrating attempt to get visas for Cambodia. I was with Roger Warner on assignment for the Smithsonian Magazine to report on Angkor, largely inaccessible since the arrival of the war there in 1970. Cambodia’s consular representation was limited, to say the least, and visas could be issued in Moscow, East Berlin, Hanoi or Saigon. In practice, things were very much controlled by the Vietnamese, whose army was still in the country, but despite Quan’s determined politeness, the bureaucratic obstructions seemed insurmountable.

The sensible approach would be to have visas issued in Saigon. But that would require Vietnamese visas, and with no evidence of a Cambodian visa, they were stonewalling. Our only communication channels with the Cambodian Foreign Ministry were one-way cables or hand-delivered packages, which could of course be indefinitely ignored. On top of that, we had no seats on any flight. As Roger put it, things were soft around the edges.

Then, one wet monsoon morning, things changed. Our fixer in Tokyo discovered that the consulate in Saigon seemed to have been notified of our visa requests. I called Quan to ask for a transit visa for the end of the week, hoping that he wouldn’t ask for proof. To my surprise, he said: ‘Why don’t you go tomorrow?’

‘I’d love to’, I replied, ‘but I can’t get on the Friday flight.’

‘I can help you’, he said. ‘Bring the passports and some open tickets now.’ Quan’s story when we met was that the previous night they had learned that a UN team, hurriedly assembled as a result of the Paris conference, was prepared to allow the press to accompany them. This was to be the first step in the withdrawal of Vietnamese troops, and the resulting international recognition of the government.

It was a relief to be on our way, even if it was in a TU-134 of Air Vietnam (one of its companions had crashed into rice-fields on the approach to Bangkok not long before, with no survivors). We landed at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut in the afternoon, all rusting and decrepit hangars, mothballed aircraft and Russian-built helicopters, and were guided smoothly and painlessly through to departures, on to a bus and out to a waiting turbo-prop of Kampuchea Airlines.

We sat waiting until a convoy of cars arrived and the UN team boarded, headed by the Norwegian General Vadset. The General was visibly taken aback by the presence of a dozen reporters, but obliged with a press conference of sorts. Clearly, the Vietnamese had been playing some games. One of the Australian reporters walked down the steps to find out from the Vietnamese officials what was happening, and returned shortly with one of them, saying: ‘I’m afraid this gentleman has some news you won’t like to hear.’ The news was that now the Cambodian authorities would like to issue our visas in town, and would we kindly deplane and fly tomorrow.

This kind of thing tends not to go down too well with journalists, and this group turned truculent. The timing of the unwelcome news, however, couldn’t have been better. Vadset’s aide Anwar explained to the official and to us that since there were no runway lights at Pochentong, and it was nearly five in the afternoon, we would have to leave immediately. No one moved. Anwar said to the official: ‘Can we talk outside?’

Through the window I could see him being persuasive. Finally, the Vietnamese and Cambodians relented. The aircraft filled with Cambodian officials and we took off. There was more confusion at Pochentong, with one airport official demanding that no one type or do any work, because this would flout ‘our sovereignty’. Hul Pany, my Protocol companion on the flight, promised to clear our entry in the city, returning an hour later true to his word. As my mediocre French was nevertheless the best in our group, I got to sign the papers for all of us, in triplicate, and we were turned loose.

In the morning we took cyclos around the city. These are Phnom Penh’s version of the bicycle rickshaw, a civilized contraption in which the passenger sits in front and has a perfect view of the street and passers-by rather than the driver ‘s trousers. But the overwhelming impression was of a city that was still waiting to fill up. From our hotel south of the Independence Monument we pedalled north up Monivong Boulevard, and the strangest sensation was the lack of noise. There were hardly any cars, just the hiss of bicycle tires. It was already ten years since the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge by the Vietnamese army and the restoration of some order out of the chaos, yet Phnom Penh was clearly not a normal city. The wide boulevards like this one that the French had built, and which in earlier times had helped to give Phnom Penh its colonial spaciousness, now exaggerated its partly unoccupied state. The Khmer Rouge had forcibly evacuated the city in April 1975, and it had still not recovered.

It had been even stranger a decade earlier, immediately after the Vietnamese invasion. The Khmer Rouge had made a special point of destroying symbols of the previous regime and of urban prosperity, sometimes in gigantic acts of vandalism. The large Roman Catholic cathedral was completely demolished, not just pulled down but dismantled, every last trace removed, so that what remained was a patch of grass in the city centre where cattle occasionally grazed. When Milton Osborne visited the site in 1981, he found pavements with mangled private cars stacked three deep, like a casual wrecker ‘s yard. One wing of the National Bank, arch-symbol of capitalism, had been blown up, and as he wrote: ‘for years afterward, banknotes from Lon Nol’s defeated Khmer Republic blew about the capital’s largely empty streets.’

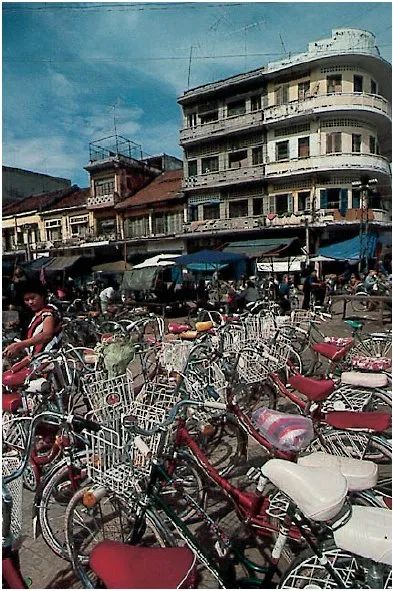

Bicycles near the Central Market, 1989

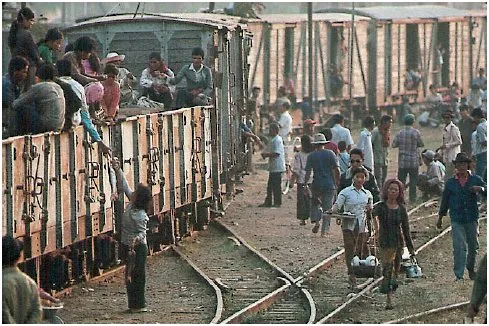

Boarding the train for Sihanoukville, 1991

Only three Western journalists were ever admitted to the hermetic Cambodia of Pol Pot’s four-year regime, one week before the Vietnamese invasion in December 1978. Elizabeth Becker, representing the Washington Post, wrote about this stage-managed visit to see Potemkin Village, Cambodia, hurriedly arranged as the regime realized that it faced overthrow. Sneaking out of the official guest-house early the first morning, as she wrote,

I met workers standing in small groups by the curb, waiting for trucks to haul them out to their jobs in the rice paddies or factories. Otherwise the city was empty. The sunlight bounced off the cement and buildings, turned Monivong Avenue into a white canyon … Behind Monivong, beyond the stage-set perfection of the boulevard, the city had been left to rot.

The Central Market had been planted in banana trees. ‘Their fanlike leaves sprouted like feathers out of stalls and vending areas. No people were in sight.’

Our cyclos turned off Monivong towards the Central Market. Here in 1989 was life, in and around the huge, grubby yellow dome and in the surrounding smaller streets. The fashion in women’s hats, which most wore, ran to bonnets in thick brushed nylon, and the colour of choice was pink, the combination bizarrely at odds with the climate. We continued to the Foreign Ministry to report our presence, but this, like many parts of the city, was empty. Totally. Perhaps everyone had gone for an early lunch. We wandered around the corridors and offices for a while, then gave up and left.

PHNOM PENH 2003

Fourteen years later, as I write now, the city is on its way back to some kind of Southeast Asian normality. Arriving at Pochentong airport on a Sunday morning, my first sight was a bumper to bumper traffic jam, heading out of town, the new middle class of Phnom Penh on their way to the beach at Sihanoukville. The novelty of this was sufficient, it seemed, to mitigate the journey, which would take most of the day there and back. Traffic, of course, transforms a city, particularly in the case of Phnom Penh which has seen so little of it, and while its wide boulevards can still handle the modern flow easily, there’s the sense that the city’s new car owners simply enjoy cruising around. The perfect place for this is the river front, and Saturday evening along Sisowath Quay is where the action is.

I sat having a drink in front of one of the small cafés, each the width of a shop-house. The Khmer owner had left to study in Paris in 1970, and so had escaped the horrors of the next decade. ‘But I returned as soon as it was possible, and I opened this place eight years ago.’ I asked him how he saw the future for the city and the country. ‘Wonderful’, he said, blinking his eyes and gesturing out towards the road and the promenade beyond.

A steady stream of traffic, Toyota after Toyota, saloons, flashy pick-ups with chromed rollbars and arrays of spotlights, Honda Dream motorbikes almost all with passengers, sometimes as many as four. On the river side of the road, vendors of all kinds were gearing up for the evening. The most ubiquitous were the food-sellers, who carried everything, including a lit charcoal stove in two panniers, balanced on the ends of a bamboo carrying pole. With a small wooden stool only a few centimetres high, they could set up a pavement restaurant in an instant, whenever they could find a customer. If the first customer seemed to enjoy the food, there was a good chance that others would be attracted, and a group of squatting diners would accumulate. Meals didn’t last long, and the clientèle would disperse as quickly as it had formed; the woman hitched the panniers on to her shoulder, scooped up her stool and moved on.

There was a continuous parade of commerce. A woman passed by, straight-backed, carrying on her head a huge open basket, something like a metre in diameter, with no effort, its contents large thin discs of rice bread. Behind her followed a man carrying stacks of small bamboo cages, each containing a small bird. The idea was to buy one of these, release the bird to its freedom in the sky and thereby earn merit, a few more Buddhist airmiles. The bird would, of course, later be recaptured and resold. A municipal street cleaner in a loose green smock uniform was evidence of the new governor’s plans to revitalize the city. Chea Sophara has been responsible for much of Phnom Penh’s resurgence.

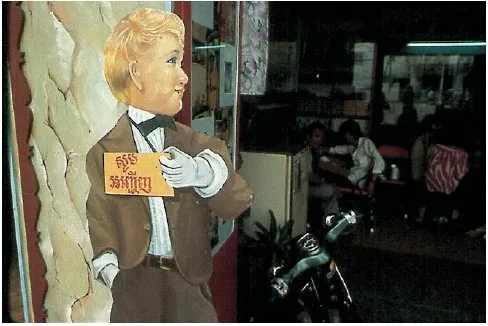

‘Come on in’, says the sign to a small café in Phnom Penh

Cigarette sellers strolled around, each carrying a small custom-made glass box perched on a wooden stand. Customization is easy in Cambodia, where labour costs much less than manufactured goods. A more elaborate invention is the cake truck, one of which was parked by the kerb opposite. A glass structure framed with aluminium, it delicately overhangs a small truck chassis, crammed with bread and pastries, the proprietor sitting inside on a low plastic stool.

Further up the promenade a medicine show had just got into full swing. Loudspeakers had been lashed to the surrounding lampposts, and the seller had started his long preamble, an entertainment involving many helpers and actors that was at least half an hour away from the final sales pitch. At this point the crowd was deep and happy to be amused. Only later would they drift away as the helpers circulated asking for money.

More popular than this was a macabre little tableau a hundred metres further up – a dead body floating in the river. One of the crew from a moored ferry boat was attempting to push the body ashore with a pole. A small crowd soon gathered, staring at the bobbing corpse, of which only the hands and face were visible, and this was the catalyst for a swarm of others, who had no idea what the attraction was. It had the temporary effect of clearing the traffic jam on Sisowath Quay, as almost all the passing motorbikes and bicycles swung off on to the promenade to see what was happening. Indeed, Phnom Penh is at the stage of ‘catching up’, when anything new is an immediate magnet. In early 2003 the city’s (and country’s) first department store opened, containing Cambodia’s first escalator. This was such a novelty that the Phnom Penhois queued to try it out, and the store had to appoint instructors to show people how to use it.

Phnom Penh still retains the charm of an old-fashioned colonial town (it definitely feels more like a town than a city), courtesy of the French architects and planners who laid out the boulevards and introduced grand houses and official buildings. There is even a unique and imposing example of Art Deco in the form of the Central Market, known popularly as the Psar Thmei, or New Market. Painted a striking yellow, the huge concrete dome with radiating wings was built in 1937. It is still home to jewellers, gold merchants and other traders.

More interesting still in its way is the Royal Palace, which to the casual visitor looks like a lesser, provincial version of the magnificent Grand Palace in Bangkok. Yet it was the French who designed this, drawing on the research that the École Française d’Extrême Orient (EFEO) was conducting into the art and architecture of ancient Cambodia. The similarity in style between this and the Thai building is no coincidence. From the nineteenth century onwards, the Thais imported Khmer culture in all its forms, notably through artists, craftsmen and scholars taken back to Siam as booty during successful military campaigns. The French, as part of their mission civilisatrice, were simply bringing it back. Being mainly twentieth-century concrete, it looks best from a distance, as reproductions tend to. The original structures, including the Throne Hall and the royal pagoda, had been in wood. Indeed, the oldest building by far is not even Cambodian. To one side of the modern Throne Hall, which now dominates the compound, and next to the palace offices, is an incongruous structure in cast iron and glass, with a domed clock tower. This ornate French pavilion was formerly used by Empress Eugénie on the occasion of the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, and was presented to the Cambodian king several years later by Napoleon III.

It was undoubtedly this Gallic enthusiasm for civic improvement and for the amenities that allowed the colons a civilized, relaxed lifestyle that made Phnom Penh so admired by all Westerners from the 1920s to the 1960s. This was a city that offered the comforts and style of a French provincial town embedded in the exotic and languid East, with its promises of discovery and pleasure. Here you could take a stroll along the Quai Norodom, a warm breeze wafting in from the Tonlé Sap river where it joins the Mekong, rustling the palms; then dine at one of the riverside restaurants such as the Margouillat; serving the huge local prawns and French wine. Or in the morning, coffee and croissants at one of the pavement cafés, perhaps a game of tennis at the Cercle Sportif. The white villas, where one could live in a degree of comfort and style probably unaffordable back home, attended by inexpensive servants, completed the Frenchness of the city.

Entrance to the Royal Palace

For visitors, all this was very welcome. There was a handful of high-ceilinged colonial hotels, including the Royal, the Grand and the Oriental (...