![]()

Gate in enclosure wall of Khonsu Temple, Karnak, 4th century BC.

1

Egyptian

Ever since Herodotus, Egypt has represented a set of mysteries to be solved. No matter where one starts - the animal-headed gods, the picture writing, the burial customs - immediately one runs up against irreducible strangeness. Now, after thousands of Egyptian texts have been deciphered and read, tombs and temples of all sizes and types uncovered and explored, industrial installations and trade routes analysed, construction methods and building histories pieced together, the civilization still carries a deep residue of strangeness.

These are the people who deify beetles, crocodiles, snakes and baboons. Who embalm and bury in elaborate graves cats, bulls and falcons. Who create whole substitute worlds, whole architectures devoted to the idea of resurrection, including actual vehicles, furniture, clothes, jewellery and cosmetics, and imitation food, servants and buildings - all one needs for a happy and successful earthly life - and then secrete them underground, as if to admit that the entire conception is essentially divorced from reality. Or perhaps just to protect it from the depredations of tomb robbers.

For these are also a people who reliably rifle tombs. Not just the impoverished and alienated or those with nothing to lose: the pharaohs themselves usurp, re-label and reoccupy their predecessors’ memorial temples, tombs and sarcophagi. Most openly of all, they turn statues of previous kings into portraits of themselves. Tomb robbery has occasionally been put in context by explaining that it blossoms in times of social disruption and economic collapse. But it is now believed that sarcophagi were often robbed before burial, thus accounting for tombs otherwise undisturbed where the caskets are found empty. So the habit seems more widespread than a desperate response in times of crisis.

Herodotus says they are the most religious people in the world, who invented the calendar to keep track of their unceasing obligations and hundreds of festivals, so frequent they became a kind of spatial structure. But many things do not fit with the picture of a sclerotically rigid society hemmed in by ritual and obsessed with death. It is true that most of the evidence for revising this view is found in tombs. Walls are painted with lively everyday activity - tending animals, making beer, hunting from boats in the marsh. Delicate stools, chairs and tent-like canopies are piled up. So we get the idea of alert attention to landscape and non-human life, and sensuous appreciation of richly furnished interiors. We only find all this life buried in tombs because anything left more exposed - most of what there was - has disappeared. Yet the suspicion persists that the innocent scenes have an ulterior purpose, if not an occult significance. Such depictions and mementos are not mainly reminiscence but also projection. They are so many allegories of resurrection that focus on activities that suggest renewal, like miraculous growth from Nile mud, archetypally dead-looking yet bursting with life. Even the footstools are coded with emblems of rebirth, winged sun disks and celestial barques.

It is sometimes assumed that the ancient Egyptians expected to ride in boats like those they buried near Khufu'u tomb. But there is a powerful symbolism that complicates the question. The celestial journey of the gods, the course of the sun across the sky and the corresponding passage of the moon through darkness are all undertaken in boats. For the most solemn religious rituals the god mounts a ceremonial boat, which is then carried by priests across dry land to another temple that becomes his temporary home. Along the way he stops at crucial moments in barque shrines, stages in the journey marked by buildings. As other narratives are composed of events, this one is made up of stylized locations and prescribed movements.

So, outside the temple of Amun at Karnak there is a Turning Shrine that depicts a change of direction in the journey, turning away from the river - whose course had been followed first along a parallel dry route, a conceptual river - and towards the temple, a progress marked by going in through one door and emerging from another nearby at right angles to it. Once inside the main temple, the procession stops again. The language that uses a building to signify a moment does not fall silent just because it has entered a building. It simply inserts a tiny building into the larger one.

Such processions are features of more than one religion. Apparently the local Muslim saint at Luxor still rides out every year in a barque procession. Favoured images in Catholic Sicily are taken through the town along prescribed courses, and the great moments in the Hindu year take place not in temples but between them, when chariots covered in carved gods like travelling wooden temples are pulled through the streets. But the ancient Egyptian version of such a pilgrimage sounds more literal-minded.

Carrying the god, as if he could possibly need our help to move about, and carrying him in a miniaturized form on a miniaturized boat rather than reminding us of his frailty, simply locates the drama firmly in the realm of representations. Egyptian symbols are taken more directly from daily life than we are used to, but they are fully symbols nonetheless. The barques in shallow pits beside the pyramid are fit for use and have every part one would need for an actual journey, but they were probably never used.

In a long sequence in the Book of the Dead the soul of the dead person is asked to name the parts of a boat, giving not their everyday but their spiritual or symbol-world names. This is the final stage in a mental ordeal in which the soul tries to organize its transport in the afterlife by asking countless questions to which he receives evasive answers. Now he is put on the spot and miraculously he knows these far-fetched names that would be utterly hopeless to guess at:

‘Tell me my name’, says the mooring-post.

‘Lady of the Two Lands in the shrine’ is your name.

‘Tell me my name’, says the mallet.

‘Shank of Apis’ is your name.

‘Tell me my name’, says the bow-warp . . .

It is a world of secret knowledge animated through and through, as if the inventor of every human device, even such taken-for-granted ones as the floor and sides of a boat, still inhabits and guards them and watches to see if you are a fit user. This disarticulated analysis is based on a visionary notion of construction as bringing dead wood to life; the boat-building is viewed as a body.

It would be hard to exaggerate the importance that the idea of the boat had come to carry for the ancient Egyptian. To probe it fully we would need to look more closely at the river and its annual cycle of flooding. But even without that we can say that the boats beside the pyramids should not be regarded as simple practical implements whose capacity has been calculated and whose eventual load is stored nearby. Unlike the Egyptian examples, Anglo-Saxon boat burials on headlands looking out to sea or surveying an estuary are actually loaded with the corpse. The boat found at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, in 1939 had been repaired: it wasn'n primarily a ceremonial object or a model but had been subjected to heavy use. It had also been defaced by the removal of essential parts to make space for a special burial compartment. The Egyptian boats aren'n often allowed into the tomb chamber. Instead, we find there a selection of prized interior fittings, not a complete set, contra the idea that everything required to start up life again is forwarded to the afterworld, but an emblematic series, enough to set the stage once, not to act out the whole play. At least so it seems in Khufu'u mother Hetepheres’ tomb, the only completely intact royal burial from the Old Kingdom found so far.

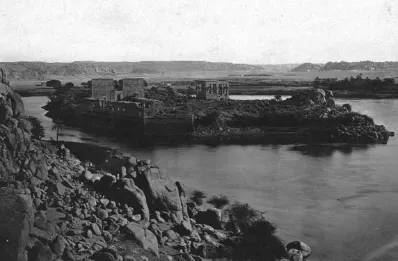

Philae, island with its collection of late temples, built from

c. 380 BC until Roman times, which were moved to a replica island in the 1970s.

The American discoverers of Hetepheres’ tomb at Giza spent almost two years unpacking her small burial chamber. Not because the contents were so numerous, but because they were found piled on top of one another, and because many had fallen to pieces, leaving only ghosts or imprints of themselves. They needed to be detached layer by layer and each newly uncovered configuration separately recorded in order to have any hope of resurrecting the vanished wooden frames (now reduced to powder) to which metal and ivory ornaments had been attached.

The process is a classic example of understanding something by taking it apart. One theory about the buried boats is that their disassembled state embodies the special power of the mind that can take apart and put back together. The full set of pieces reveals the ingenuity of maker or creator more fully than the simpler complete object would.

Disassembly, sometimes brought on by external necessity, has often helped in understanding Egyptian architecture. The late complex on the island of Philae in Upper Egypt, the last place the old Egyptian religion was practised, had to be taken apart and moved in the 1970s before the Aswan High Dam flooded its original site, already periodically submerged by the old dam. This emergency resulted in a clearer idea of earlier stages, revealing superseded buildings and establishing a different sequence of construction.

Another, more dramatic recovery of lost stages through disassembly came from the chance discovery of pieces of the heretic Pharaoh Akhen-aten'n destroyed temples at Karnak, reused as filler in the Second Pylon and in foundations of the Hypostyle Hall. Further fragments have turned up inside the Ninth Pylon, secreted in such an orderly way that they need only be mounted in reverse order to reveal a whole wall carved with lively scenes of workers putting up the vanished palace of this king.

Akhenaten'n are just the most violent instances at Karnak of later stages consuming earlier ones. Continually feeding on themselves, such temples digest earlier stages and the result is a gigantic jigsaw puzzle, a confusion that nonetheless allows experts to reconstruct from partial remnants many vanished kiosks, gateways and courts.

Of course, there were many centuries available for these changes to occur, but the unceasing series of revisions does not fit with our ideas of this civilization as unchanging. In the New Kingdom royal burial practices diverged into bewildering elaborations. Seti I was buried in Thebes, where his mortuary temple is one of the biggest on the entire West Bank. But he also built an elaborate mortuary temple at Abydos, an older and apparently unsuperseded funeral site, later made special by burial there of the reassembled Osiris, pattern of all other resurrections.

Osiris provided the template for multiple burial sites. His dismembered body ended up in thirteen locations, each of which commemorated the burial with a shrine. The dispersed god was also reassembled by Isis who had to fabricate the missing fourteenth part, the penis, which had been eaten by Nile carp. The story of this god, in which he is both found in many places and reunited in one, reflects the Egyptian love of stringing out simple entities into endless series of almost indistinguishable parts and concurrent claims of wholeness.

French kings were sometimes buried in three places, the heart in one, viscera somewhere else, and the rest somewhere further still, each of the locations carrying a different meaning, each deposit provoking special devotions of its own. Egyptian multiple burials - selected body parts removed and stored separately from the main corpse - seem to have been kept together in a single structure, but the second temples somewhere else would still have their own cult observances attached and thus promote a more complex memorial practice.

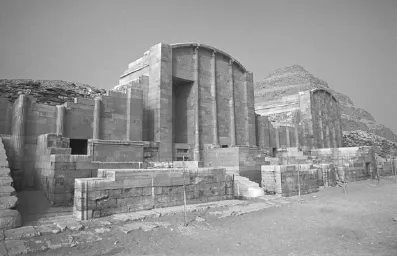

In fact, monumental architecture in Egypt begins with a royal mortuary precinct that is a kind of city in itself. Djoser'r tomb at Saqqara is the oldest monumental stone construction. His step pyramid, the first, consists of six platforms on top of each other, decreasing regularly in stages. The form derives from a traditional memorial in the form of a low mound of mud brick that looks like a windowless room or a smaller version of a single one of the Djoser steps. These were called mastabas by workers on nineteenth-century excavations, from the Arab word for bench. Probing of Djoser'r pyramid has shown that it began as a mastaba and arrived at its present dimensions by several increments. Intermediate stages, intended as final to begin with, were ambitiously extended to arrive at the heroic mass we have now. The result seemed so remarkable that the architect't name was preserved and he acquired legendary status. Imhotep, also remembered as a mathematician and physician, was later deified, and through the link with medicine became confused with Aesculapius.

Djoser'r complex is stone-built throughout, but some of the forms reproduce other kinds of construction. Outer walls, made of fine ashlar, resemble brick fortifications. A grandiose entrance gallery, whose columns imitate bundled reeds, was roofed in stone slabs carved to look like huge logs. Perhaps the most interesting feature of all is the Sed court, into which you emerge from the gallery. This is framed by delicate pavilions representing provinces of Egypt. Forms are flimsy, recalling slender wooden posts supporting tent roofs or thatch. Some are fluted and, in view of their refinement, were dated to the Greco-Roman period by early twentieth-century investigators. These are dummy chapels of solid stone with no real enterable space. Crucial for the Sed festival ritual were boundary markers towards the end of the course. Holding appliances whose function is not well understood, the king ran between the markers, proving his vitality and reasserting the union of the two halves of Egypt under his rule.

Stepped pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara,

c. 2650 BC. The earliest monumental building in stone and the first by a named architect, Imhotep.

Egypt, as a whole made of parts, was conceived as Upper - the southern part of the country towards Nubia, represented by the colour white and the lotus flower - and Lower - the northern part towards the Delta, represented by red and the papyrus bloom. The king united these differences, symbolic shorthand for cultural variety, most vividly in his regalia, which included a composite double crown, the Upper Egyptian cone inserted in the Lower Egyptian ring. The most complete representation of the Sed festival that cemented the union occurs many centuries later on rediscovered blocks from Akhenaten'n destroyed temples at Karnak, where a long passageway connecting a temple to the palace depicted the festival in great detail.

Dummy pavilions in Djoser complex at Saqqara, imitating canvas tents in stone.

Djoser set the pattern for royal burials of a walled mortuary complex centred on a pyramid. A few more stepped pyramids were built, and then came the idea of filling in the steps to make a single sheer slope. The earliest attempt to survive, the Bent Pyramid at Dashur, is one that went wrong. Too steep, it began to collapse, and attempts to shore it up resulted in a crooked profile. Soon after this time pyramids began to be accorded elaborate names. The first was called ‘Sneferu appears in glory’, and the famous triad at Giza was named ‘Horizon of Khufu’, ‘Khafre is great’ and ‘Menkaure is divine’.

Names convert the buildings into beings and make a confusion between the person and the tomb; the large looming shape becomes articulate. The names are like charms to be repeated over by the elect, and it is most unlikely that they were in common use. I...