![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Origins of Dismal Swamp Marronage

Freedom Wears a Cap which Can Without a Tongue, Call Together all Those who Long to Shake of The fetters of Slavery.

— Governor Alexander Spotswood to Virginia House of Burgesses, 1710

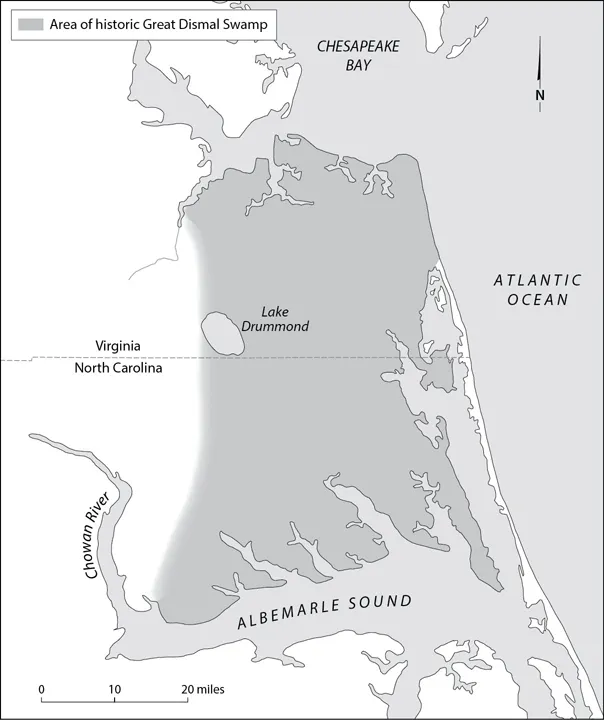

THE GREAT DISMAL SWAMP is one of the most massive landforms along the east coast of North America, and as such, every population encountering it has had to address its presence in one way or another — whether as foragers, settlers, or fugitives. Sprawling over 2,000 square miles, the Dismal was a hunting ground and sacred space for Indigenous people since time immemorial and hundreds of years before Europeans arrived in the region. As colonizers attempted to “subdue” the North American frontier and settle the broad Tidewater, the swamp presented one of the most significant obstacles to their advancement — it was nearly impassable, and terrifying to them in its dark mystery. However, what was an impediment for colonial society became a great defender of those who sought to escape it. Indigenous refugees, white servants attempting to escape the stifling Virginia plantation complex and often their indentures, religious nonconformists, and self-emancipating Africans put the swamp between themselves and the Old Dominion, and developed a dissident society beyond any colonial authority.

Though an open and relatively egalitarian community developed in the swamp, Virginia officials deemed the area a “rogues’ harbor.” When the expansion of a landed elite class with the support of colonial officials finally overwhelmed, most of this community’s members despairingly resigned themselves to the dominion of the gentry — but not all. Some moved from the edges of the Great Dismal Swamp and into its interior to join a small but growing multiracial population of refugees. The swamp may not have offered a life of leisure and comfort, but it allowed its residents a free existence beyond the scrutiny and practical reach of authorities on the outside. From these origins and over 200 years, a maroon population grew that at once fascinated, terrified, and repelled white outsiders. For disaffected exiles of the Tidewater, however, the swamp drew them in like a magnet, enabling them to begin to chip away at the foundation of the planter society that had enslaved and marginalized them. There would be no “masters” in the Dismal Swamp, only free people.

The Prehistoric Swamp

The Great Dismal Swamp lays in what is called the embayed section of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, which consists of three wide and gently sloping terraces separated by longitudinal, eastward-facing escarpments, or sudden elevation changes. It is bounded to the north by the Churchland Flat (just south of the James River), to the east by the Deep Creek Swale, to the south by a transition zone surrounding the mouth of the Pasquotank River basin, and to the west by the Suffolk Escarpment — otherwise called the Suffolk Scarp — the first main character in the Dismal Swamp drama.

The Suffolk Scarp sits fifty miles inland from the present Atlantic shore, itself formerly the ocean’s shore during the Pleistocene around 2 million years ago. It rises twenty to thirty feet higher than the lower coastal plain and falls eastward to the ocean. With a handful of lesser scarps and ridges south of the James River, the Suffolk Scarp laid a scene for a dramatic human drama to come. The Scarp interrupted the general west to east flow of the landscape, and of waterways and rivers, from the mountains to the sea. North of it, the James River, the Elizabeth, the Nansemond, and other lesser waterways flowed as “a superhighway” east into the Chesapeake Bay, wide open to the Atlantic and the rest of the world. South and west of the Scarp, waterways including the Chowan and Roanoke flowed more slowly and southerly into the Albemarle Sound. Though a rich and beautiful estuary, it was bottled up by accumulating sediments carried by southern-flowing longshore currents (the Outer Banks), making it, in Jack Temple Kirby’s comparison, a Carolina cul-de-sac rather than a Chesapeake highway, with no safe outlet to the sea. The scarp thus created a Tidewater hinterland and determined the travel and settlement patterns of the haves and have-nots long before humans arrived on the scene.1

By the end of the Pleistocene and last glacial period around 12,000 years ago, a warming climate raised sea levels as well as inland freshwater tables, and in the increasingly boggy area east of the Suffolk Scarp fast and densely growing vegetation clogged stream valleys with organic matter. As the detritus accumulated faster than it could decay, it built up a layer of peat twenty feet thick in places, at a rate of accumulation of a foot or more per century.2 By 4,000 BCE perhaps 1,000 square miles of the infant swamp was swaddled with a blanket of peat. Two millennia later, a mature Great Dismal Swamp covered 2,000 square miles and reached from what would become Suffolk, Portsmouth, and Norfolk to the north and the Albemarle Sound to the south.3

Historic Great Dismal Swamp

Near the western center of the swamp was Lake Drummond, a roughly three-by-five-mile (3,100 acre) oval named after the first colonial governor of North Carolina. Today, the lake sits eighteen feet above sea level (one of the highest points in the swamp) and is six to seven feet deep at normal levels. Five rivers draw their waters from Drummond and the Dismal and flow out from its depths, three into North Carolina and two into Virginia. Drummond’s origins are uncertain, and theories include a meteorite impact, tectonic shift, or massive peat fire several thousand years ago. A local Indigenous legend attributes the lake’s genesis to the reign of terror of the great Firebird, who lived in the Dismal and whose smoldering nest seared a hole into the center of the swamp.4 Drummond’s sublime beauty is also legendary —“One thinks if God ever made a fairer sheet of water,” a hunter wrote in 1908, “it is yet hidden away from the eyes of mortals.”5

Much of the swamp, as might be expected, is covered in water and the vegetation that thrives therein. There are miles and miles of reeds and cattails in open spaces, duckweed and cypress knees under dense swamp forest canopies. Islands of high ground dot the landscape, ridges heavily wooded with Atlantic white cedar, maple, blackgum, tupelo, bald cypress, sweetgum, oak, and poplar.6

Since the region’s human prehistory, the Great Dismal Swamp was the central feature of the Tidewater. For thousands of years before Europeans entered their world and called it “new,” Indigenous people had lived along this coast, even as the great swamp was maturing. Early Paleo-Indians (Early Woodland Adena culture, 1000 BCE–200 CE) were farming and hunting in and around the Dismal at least by the third century BCE.7 Very little else is known of their history, beyond that they once existed.8

By the early sixteenth century, more substantial Native American groups had settled at the periphery of the Dismal. The Croatan, Hatteras, Chowan, Weapomeiok, Coranine, Machapunga, Bay River, Pamplico, Roanoke, Woccon, Nansemond, and Cape Fear people spoke Algonquian-related languages and had developed a culturally sophisticated, if politically unstable society. They most often lived in small coastal villages, with as many as thirty dwellings enclosed by fortified palisades. Their standard of living was not as abundant as their more numerous and powerful neighbors to the west, the Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora, Catawba, and Cherokee, and to the north, the Powhatan.9 But they were not alone in the world.

Europeans Settling Northern Carolina

By the early sixteenth century, European explorers had reconnoitered the area that would one day be called Carolina and Virginia. The first European ships to sail along the Dismal Coast were captained by the Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano in the service of France in 1524. Verrazzano’s account of a New World Eden inspired great interest in the region. The first Spanish attempt at settlement was attacked by Indigenous people and ultimately fell to the first North American slave rebellion in 1526. When the Spanish survivors fled in the fall of that year, they left behind dozens of enslaved Africans. Four decades before the establishment of Saint Augustine and eight decades before Jamestown, dozens of Africans, nameless to history, continued their lives as free people beyond the control of Europeans. Perhaps the grandchildren of these first permanent Old World settlers made the acquaintance of those Englishmen left behind at the failed and mysterious “Lost Colony” Roanoke settlement in the late 1580s.10

European explorers had already made contact with Indigenous people deeper in the interior. Some they befriended, others they enslaved or killed. Many they sickened with diseases that moved faster than they did, and so Indigenous people of the Tidewater and vicinity sometimes began falling ill and dying before they ever saw a white face. Europeans were seldom far behind the epidemics they unleashed. During his celebrated journey through the Carolina colony in 1700, John Lawson made remarkable observations about the cultures, interactions, and communications among the interior tribes, and in several instances mentioned the disease and enslavement that had often befallen them. He was completely silent regarding the coastal people. Most of these, it seems, had disappeared, relocated, or merged into loosely assembled composite tribes.11 These people retreated to the most marginal lands not yet coveted by white settlers or larger Indigenous nations, including the edges of the Great Dismal Swamp.12

Although the first “official” permanently settled colony was finally established at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, small numbers of Old World settlers had long inhabited the region to the south, though they left behind next to nothing for the historian to tell their stories. As historian Wesley Frank Craven admits, “It is impossible to speak definitely of the first permanent settlement of Carolina.”13 Their numbers grew as bound laborers, mostly white servants, escaped their indentures in Virginia and sought freedom and independence on the southern frontier.

White servants had attempted to escape from Jamestown within months of its settlement and especially during the “starving time” of 1609–10 when, rather than survive on dogs, boot leather, and the occasional desperate act of cannibalism, they sought succor from the neighboring Powhatans. “To eate,” one beleaguered settler wrote, “many our men this starveinge Tyme did Runn away unto the Salvages whom we never heard of after.” The exodus could not be stopped, even under threat of execution. The occasional servant prone to attempted escape might even be “bownd fast unto Trees” to keep them in place.14 They understood that surviving starvation might only mean overwork in a tobacco field and abuse at the hand of one’s master. In practice, indentured servitude differed very little from outright slavery.15

Servant flight remained an urgent concern of planters for decades. In March 1642, the Virginia Assembly levied fines for anyone caught aiding or abetting “runaway servants and freemen,” and prescribed branding for the offending servants.16 Some might be sheltered by sympathetic Virginians, but increasingly fugitives turned their gaze on the frontier, beyond the horizon where Virginia authorities had any real political control. The likely destination for those escaping was “the swamps and forests to the southward.”17

Virginians had explored northeastern North Carolina in 1608, 1622, and 1643 and found little that interested them.18 Soil conditions and topography south of Virginia were seldom attractive to planters hoping to extend their agricultural reach. As one historian puts it, Virginians exploring southward may have found plenty of “rich bottom land,” just at the bottom of swamps, and not the kind on which to expand Virginia’s agricultural successes. The lack of accessibility and treacherous landscape of the region further dissuaded settlers. Most problematic was its coastline, where England’s first attempt at permanent settlement of Roanoke had failed spectacularly. The treacherous northern Carolina coast earned the nickname “graveyard of the Atlantic.”19 The shifting shoals of the Outer Banks discouraged the approach of large vessels, and most small farmers were forced to haul their goods overland to and from Virginia. Even the overland approach was frustrated by swamps and eastern marshlands. The Great Dismal Swamp, straddling the Carolina/Virginia boundary, was in and of itself an impassable obstacle to trade. The King’s Highway, no more than a “rough road” that eventually connected Edenton, North Carolina, to the south and Norfolk, Virginia, to the north, snaked through and around the swamps, required several fords, and skirted far west to stay clear of the Great Dismal.20

The Albemarle Sound, an estuary situated at the confluence of the Chowan and Roanoke Rivers, was the only access most northern Carolinians had to the Atlantic. Only the Cape Fear River emptied directly into the ocean, and its mouth was 200 miles from the Virginia border and remained undeveloped until the 1720s. For over half a century of proprietary rule, most northern Carolinians lived in or around Albemarle County with no immediate access to a seaport. Other rivers used for trade emptied into either the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds, and only small vessels could navigate the shallows from sound to ocean.21 Even the most modest profit-seeking northern Carolinians believed their home region to be a “place uncapable of a Trade to great Brittain.”22

Official attempts by the English to colonize the region between the James River and Spanish Florida were disorganized and ineffective. In 1620, King Charles I of England granted a charter to his attorney general, Sir Robert Heath, to establish a new colony between 31 and 30 degrees north latitude, of men “large and plentiful, professing the true religion, sedulously and industriously applying themselves to the culture of the said lands and to merchandizing; to be performed and at his own charges, and others by his example.” However, Heath set no example. “Carolana” was never fully brought into existence because of the political turmoil that erupted with the English Civil War. Heath fled to France in 1645, forfeiting his charter, and the territory remained free of organized E...