![]()

[ chapter one ]

America as Niagara: Nature as Icon

ANTHONY PHILIP HEINRICH

The War of the Elements and the Thundering of Niagara

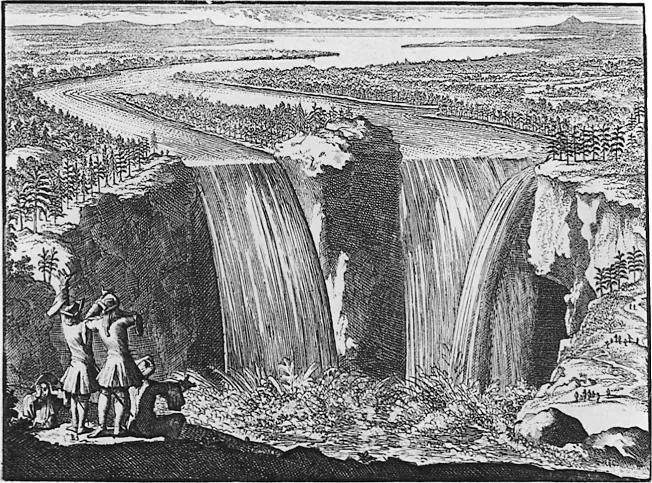

IN 1697 the first known image of Niagara Falls appeared. The engraving was the work of an unidentified Dutch printmaker and was part of a book written by Father Louis Hennepin entitled Nouvelle découverte d’un très grand pays situé dans l’Amérique. Hennepin observed the Falls as a member of the expedition of the French explorer Robert LaSalle to America in 1678–82. The missionary priest later devoted two chapters of his travelogue to Niagara. Within two years the book was published in Dutch, English, German, and Spanish, and by the early 1700s several editions circulated.1

The art historian Jeremy Elwell Adamson assessed Hennepin’s observations: “The geologically ignorant author had described the ‘wonderful Downfall’ as composed of ‘two great Cross-streams of Water, and two Falls, with an Isle sloping along the middle of it.’ The ‘Gulph’ into which the river dropped, he declared, was 600 feet deep. There were no mountains in the vicinity, he noted, and from its commencement at the eastern end of Lake Erie, the broad stream flowed gently over a flat plateau. Unexpectedly and ‘all of a sudden,’ the river plunged over the ‘horrible Precipice,’ terrifying the priest with the ferocity of its fall.”

Adamson then considered the implications for a visual artist: “Although it is an imaginary view, this initial image nonetheless presents a surprisingly successful solution to the basic question confronting all artists who visited the site itself: how to suggest the vast dimensions of the cataracts and extensiveness of their setting, yet, at the same time, express the psychological impact of the scene. … The immensity of the scene is conveyed by juxtaposing small figures against the waterfalls. The ‘surprising and astonishing’ effect Niagara had upon the mind is suggested by the gesticulating European in the left foreground.”2

The anonymous Niagara engraving was one of just three illustrations in the book, but it provided the first glimpse of the continent for thousands who had never set foot in the New World.3 The Falls quickly became the most recognized natural phenomenon identified with North America; they marked the place as unique.

Numerous images followed, portraying the Falls as vast, limitless, powerful, and wild. The wildness of the place was conveyed by variously clad Indians, animals native to the continent including beavers and eagles, and, later on, rattlesnakes—figures that would be adopted as Revolutionary War symbols. Eighty years before the nation existed as a polity, the Falls came to represent America as a vast, verdant, untamed place fraught with danger and full of untapped power.

Over the next two hundred years, Niagara’s iconographic power persisted even as its meaning morphed. By the 1820s hundreds of guests were accommodated at Niagara’s local hotels. In the same decade that Emerson’s essay “Nature” (1836) cast America as the unique site of communion with the universal Being, the Oversoul, Indians disappeared from Niagara images. The wild and exotic Niagara was replaced by the sublime Niagara.4 Images of Niagara reflected the changing perception of the nation (both its own and others’) as it evolved from wilderness outpost to promised land to industrial giant.5 Thomas Davies, Thomas Cole, John Vanderlyn, John Trumbull, George Willis, Henry Davis, Thomas Chambers, John F. Kensett, Jasper Cropsey, Herman Herzog, Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, John Twachtman, and, most famously, Frederic Edwin Church all painted the Falls, as did a host of lesser names. Their renderings are as different as the moods of the waters.

The flood of visual imagery was echoed in equally ardent efforts to capture the cataract in poetry and prose. Oliver Goldsmith, James Fenimore Cooper, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Charles Dickens, Matthew Arnold, and Richard Watson Gilder responded to the Falls and variously interpreted its restless power as the force behind the nation’s “uniqueness and promise.”6 Dickens’s rhapsody on the Falls that appeared in American Notes in 1842 was easily the most oft-quoted description of the cataract. A brief excerpt gives a sense of the tone: “Then, when I felt how near to my Creator I was standing, the first effect, and the enduring one—instant and lasting—of the tremendous spectacle, was Peace. Peace of Mind … What voices spoke from out the thundering water; what faces, faded from the earth, looked out upon me from its gleaming depths; what Heavenly promise glistened in those angels’ tears, the drops of many hues, that showered around, and twined themselves about the gorgeous arches which the changing rainbows made! … I think in every quiet season now, still do those waters roll and leap, and roar and tumble, all day long; still are the rainbows spanning them, a hundred feet below.”7

This was matched in ardor if not in length by John Quincy Adams’s “Speech on Niagara Falls,” delivered just days after his visit in 1843. The former president informed the Buffalo audience, “You have what no other nation on earth has. At your very door there is a mighty cataract—one of the most wonderful works of God.” He concluded that the waterfall, with its omnipresent rainbow, was “a pledge from God to mankind.”8

In 1860 the Reverend Edward T. Taylor addressed a gathering of religious leaders in Buffalo, New York, who had taken an excursion to the Falls. His remarks attest to the nationalistic pride still stirred by the natural wonder: “What does it represent? What does it resemble? Does it not resemble our country,—our vast, immeasurable, unconquerable, inexplicable country?” Imbuing the cataract with religious significance, Taylor observed: “After you have said Niagara, all that you may say is but the echo. It remains Niagara, and will roll and tumble and foam and play and sport till the last trumpet shall sound. It will remain Niagara whether you are friends or foes. So with this country. It is the greatest God ever gave to man. … Niagara is like our gospel. It never freezes in winter nor dries up in dog-days. You never need to come and go away with a dry bucket. … Our gospel is adequate to all the wants of the world. … It is as powerful as Niagara!”

With undisguised Manifest Destiny thinking informing his speech, he went on: “It is our own. God reserved it for us, and there is not the shadow of it in all the world besides. I have travelled far, and have seen the best of all the countries of all this world, and there is but one United States of America in the world.”9

The Civil War would alter the unchallenged national significance of the Falls, but in the late 1870s Longfellow’s collection Poems of Places, which included at least ten poems by as many writers, testified to the continuing broad appeal of the Falls as an artistic subject. Amateurs joined the Niagara chorus as hundreds of travelers wrote their own original accounts, which were published in local newspapers. Scholars too were “Niagaraized,” explaining the changing significance of the natural and cultural phenomenon in articles, dissertations, and books.10

A sense of the inspirational power of Niagara can be gleaned from the Anthology and Bibliography of Niagara Falls published in 1921 by Charles Mason Dow, an indefatigable guardian of the Falls and a former commissioner of the State Reservation at Niagara. Dow’s Anthology became its own tribute to the natural phenomenon. In it he reproduced numerous engravings, including the one of the Falls that appeared in Hennepin’s volume. He included copies of paintings, maps, excerpts from accounts, and scientific writings, and he listed hundreds of sources containing information on the Falls. He hoped his efforts conveyed “some slight idea of the great extent of Niagara literature.”11 The two volumes totaled 1,423 pages.

After Louis Hennepin, Cataracte de Niagara, Paris, 1757. Courtesy of the Charles Rand Penney Collection.

Dow’s second volume opened with a chapter devoted to music, poetry, and fiction. In addition to enumerating the more widely known literary works that focused on Niagara, the former commissioner listed music-related literature inspired by the Falls. While many of the poems are identified as “hymns,” they are clearly not intended to be sung. The single musical composition that he cites is one written by the touring Norwegian violin virtuoso and composer Ole Bull, entitled Niagara. This unpublished piece for violin and orchestra was composed in New York in October 1844 after a visit to the Falls, and Bull premiered it in public on 18 December of the same year. Bull considered it “the best composition [he had] written,” although critics did not agree.12 In a particularly stinging review of Niagara, George Templeton Strong opined: “In the opening of ‘Niagara’ one might discover (if he knew the subject) the image of a flowing river gradually quickening its current and becoming broken with rapids. Then came a grand explosion from the orchestra, intended to express a cataract, and after that I could recognize no meaning in the piece unless the artiste meant to express that he’d gone over the falls with the crash that described them and was drifting about in the fragmentary water below.”13

A review of Bull’s first American concert a year earlier that had appeared in the Herald had actually evoked the imagery of Niagara to describe audience reaction: “It was a tempest—a torrent—a very Niagara of applause, tumult, and approbation throughout the whole performance.”14 It would seem that when it came to Bull, Niagaras flowed in all directions.

Dow lists only one other distinctly music-related item, an article by Eugene Thayer (1838–89), the German-trained American organ virtuoso who often accompanied Bull when he toured America.15 Thayer’s four-page study entitled “Music of Niagara” appeared in Scribner’s magazine in February 1881. It began: “It had ever been my belief that Niagara had not been heard as it should be, and in this belief I eagerly turned my steps hitherward the first time a busy life would permit. What did I hear? The roar of Niagara? No. Having been everywhere about Niagara, above and below, far and near, over and under, and heard her voice in all its wondrous modulations, I must say that I have never, for a single instant, heard any roar of Niagara.”16

It gradually becomes clear that Thayer’s goal is not merely to argue whether Niagara “roars,” a term the author never defines but that a reader infers to mean a loud, uncontrolled noise antithetical to music. Rather, he uses quasiscientific explanations based upon the vibrations of the overtone series to explain the Falls’ sound as the “great diapason—the noblest and completest one on earth … the same tone which for ages has ascended in praise of Him who first gave it voice.”17 Thayer therefore not only explains the sound he hears, he identifies it as the voice of God. Using rudimentary charts showing a harmonic series built upon G, comparisons between the height of the Falls and the length of comparatively proportioned organ pipes, and repeated assertions regarding the dependability of his hearing, Thayer explains Niagara’s music: “From the first moment to the last, I heard nothing but a perfectly constructed musical tone—clear, definite and unapproachable in its majestic perfection; a complete series of tones, all uniting in one grand and noble unison, as in the organ, and all as easily recognizable as the notes of any great chord in music. And I believe it was my life-long familiarity with the king of instruments which enabled me to detect so readily the tone-construction of this mighty voice of the ‘thunder of waters.’ ”18

Not content to address pitch alone, Thayer also clarifies the rhythm of the Falls. “What is its rhythm? … Its chief accent or beat is just once per second! Here is our unit of time—here has the Creator given us a chronometer which shall last as long as man shall walk on earth. It is the clock of God!”19 Thayer provides an example of the rhythm showing a half note at 60, and beats divided into increasingly small groups of threes, perhaps a subtle reference to the presence of the trinity. The author concludes: “What is the quality of its tone? Divine! There is no other word for a tone made and fashioned by the Infinite God. I repeat, there is no roar at all—it is the sublimest music on earth.”20

Thayer’s remarks are noteworthy for a number of reasons. First is his insistence upon the religious meaning of the Falls: Thayer’s pairing of Niagara with a sacred, sublime Deity and his insistence that it was the natural incarnation of God reflected an attitude current in the 1830s and 1840s, and resuscitated in the 1850s by the Hudson Riv...