- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Teachers and curriculum specialists are exposed to many ideas from educational leaders, but it is difficult to know which ones can be transformed into meaningful learning experiences in the classroom. Concept-Based Instruction:

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Concept-Based Unit Design

Leading Instructional Philosophies

DOI:10.4324/9781003233770-2

Part of being a teacher is improving your craft. There are many experts in the field of education in a variety of areas: diversity, curriculum, one-to-one implementation, social-emotional learning, etc. With so much to consider, it’s no wonder that schools, administrators, and teachers feel overwhelmed. As educators look for approaches that will fix the problems in their schools, they are often faced with poorly planned implementation, shifting strategies, and quick-changing ideas to try—without ever giving last month’s initiative enough time to determine instructional or learning effectiveness.

Concept-based curriculum is an approach that breaks down the silos of specific subject areas and brings them together through a broad-based theme. It provides higher level thinking and makes cross-curricular connections. Students not only learn facts and specific information, but also find answers to questions about why and how the content is important.

This book demonstrates how to blend many of these ideas in a disciplined format. Although every attempt has been made to stay true to the philosophical framework of the prestigious educational leaders discussed, this book is a synthesis of these works and will result in a slightly different interpretation of these ideas. The reader will notice that the format is gradual as opposed to being rapid, confusing, and frustrating; this ensures that practitioners can delve into new ideas at a pace that ensures success. Teachers quickly abandon ideas or become frustrated when something is implemented too quickly or without deliberate thought.

As with any promising idea, it is necessary to create a plan and stay the course with minor adjustments along the way. Often educators may neglect to reflect on the practice being implemented. If there is research to support complex implementation, then there must also be time built in to give it a chance. Starting with curriculum mapping and ending with thinking skills, teachers will learn how to include concept-based unit development and backward design to create deeper and more relevant learning. The works of prolific educators Carol Ann Tomlinson, John Hattie, Robert Marzano, and Richard DuFour will be reviewed to support the practice, development, and depth of these ideas.

Curriculum Mapping: Heidi Hayes Jacobs

Many schools and districts have gone through the “unpacking” of the standards—a process that adds clarity regarding the interpretation of rigor. The process of digging deeply into each standard and determining what skills need to be implicitly and explicitly taught is critical. This process can lead to determining what prerequisite skills are required before students are ready to learn new skills. Jacobs (1997), the premier expert, defined the process of curriculum mapping in this way:

Curriculum mapping is a procedure for collecting data about the actual curriculum in a school district using the school calendar as an organizer. Data are gathered in a format that allows each teacher to present an overview of his or her students’ actual learning experiences. The fundamental purpose of mapping is communication. The composite of each teacher’s map in a building or district provides efficient access to a K–12 curriculum perspective both vertically and horizontally. Mapping is not presented as what ought to happen but what is happening during the course of a school year. Data offer an overview perspective rather than a daily classroom perspective. (p. 61)

Curriculum mapping serves as a series of steps for deciding what curriculum is necessary and then monitoring the planned curriculum (O’Malley, 1982). This process, which originally made use of index cards and charts, can now be completed in an electronic format, although many teachers appreciate having a large image and being able to physically move cards (or sticky notes) within the diagram. The concepts communicated by Jacobs (1997) highlight the importance of starting with this practice to look for gaps and overlaps throughout the year in all core subject areas (literacy, mathematics, writing/language, social studies, and science). Additional ancillary subjects should be included. Table 2.1 in Chapter 2 demonstrates an example of an integrated map to assist with better understanding.

Concept-Based Curriculum: H. Lynn Erickson

Once the year has been mapped out, the next step would be to identify what students are expected to know, understand, and be able to do in each area. The concept-based unit objectives extend the knowing, understanding, and actions in order to make connections to higher thoughts. A broad-based theme is used to connect multiple subjects. Throughout the implementation, students think deeper as they experience curricula and are guided to make connections in multiple ways.

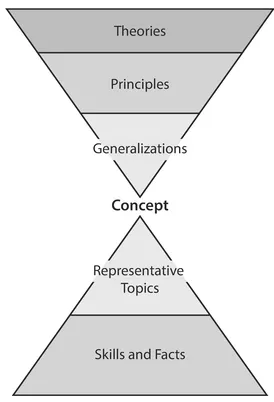

In a recent book on concept-based curriculum, Erickson, Lanning, and French (2017) introduced the idea of including process skills, especially in writing. Figure 1.1 is an adapted version of the concept map. Starting at the bottom of the lower triangle, the skills and facts are at the basic level. These come together to create a topic, such as grammar or ecosystems, at the top of this bottom triangle. Teachers can then review the topics to look for a shared concept shown in the rectangle, such as “a cause creates an effect, reward, or consequence.” Students then expand from generalizations to learn principles or interact with theories. Teachers need to be prepared to not have a perfect or correct answer. When the class wrestles with the concepts together, the knowledge gained is respectful of others’ ideas, requires justification for the line of thinking, and causes students to take on different perspectives.

Components of Erickson's Concept Map

Theories are evidence-based and occur in nature or are a specific behavior. Examples would be “The conspiracy of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy” and “Global warming is destroying the polar ice caps.”

Figure 1.1.Concept map (Erickson, Lanning, & French, 2017).

Principles state a relationship between two or more concepts: “The Earth revolves around the sun and is kept in orbit due to gravity” and “All even numbers end in 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8, and divide in half evenly and without a remainder.”

Generalizations are the “big ideas” from a learning experience and are related to the topics of study and concepts. These are critical learnings and understandings. Examples would include “Different factor pairs can create the same product” and “Rules and laws are necessary for order in a civilization.”

Concepts are transferrable to other disciplines, are intangible because they are ideas, and are commonly understood. For the purpose of this book, they are broad-based and include examples like “Relationships,” “Structure,” and “Culture.”

Representative Topics are found within a content area or subject, such as “Westward Movement,” “Space,” and “Trigonometry.”

Skills and Facts are determined by the content standards of the state.

After reviewing the aforementioned theories, principles, generalizations, concepts, topics, facts, and skills, some adjustments might be made to put logical topics in the core subject areas to create cohesive conceptual themes without causing a disconnect of progression. This part of the unit design could take the largest amount of time to accomplish. Having a logical, understandable, and detailed curriculum map will expedite this process.

Essential Questions and Enduring Understandings: Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe

Wiggins and McTighe introduced Understanding by Design in the late 1990s. It is a framework for improving student achievement in which the teacher is viewed as a designer of the learning with close attention paid to the curriculum standards (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Teachers determine how students are to learn and engage with the material, and align assessments to match the goals and expectations. They plan for what students are able to know, understand, and do. Wiggins and McTighe identified these as Stage 1, or the desired results. The goal is to make the learning experiences transferrable to other disciplines and to real-life situations.

Stage 2 involves the evidence of learning, which can be established in several ways (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Will it be through a performance-based task at the end of a unit that demonstrates an application of the targeted learning in a new and real-life situation? Will it be through a formative short-term quiz or test, or will it be a report or presentation? Through questions like these, teachers must think like assessors. Wiggins and McTighe identified true understanding in one of the following ways, also known as the six facets of learning:

- explaining concepts, principles, and processes;

- interpreting by making sense of the text, a set of data, and experiences;

- applying in new contexts;

- seeing a different perspective or point of view;

- demonstrating empathy through taking the position of the other person; and

- having self-awareness of what the learning experience was like.

Deciding which facet to implement depends on the subject and content being learned.

Once these elements are identified, Stage 3, the unit plan or learning plan, can begin (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Teachers may know this stage as backward design. Educators decide what evidence will prove that students have met the learning goals. To truly have a deep understanding, students need to be given numerous opportunities to interact with the information, with the teacher taking on the role of facilitator and coach rather than dispenser of information. These steps are compatible to those used in designing a concept-based unit.

Much has been written about Erickson’s (2012) expertise in working with the International Baccalaureate (IB) curriculum design and how comparable it is to Wiggins and McTighe’s (2005) essential questions and enduring understandings. Although each subject area can have its own essential questions and enduring understandings, connections can be made across multiple subject areas with deeper meaning. Wiggins and McTighe’s essential questions and enduring understandings serve as references for student thinking, discussion, conversation, and written word. Units should take place over several weeks and include checkpoints along the way to ensure that the complexity that students will experience is connected to the learning. Emphasis will then be placed on the result to demonstrate evidence of what students have gained.

Drake and Burns (2004) summarized Wiggins and McTighe’s three stages of curriculum planning in their book, Meeting Standards Through Integrated Curriculum. Wiggins and McTighe developed these stages to help teachers with the development of the unit and stay focused on the standards, thus securing the evidence of the learning. Wiggins and McTighe determined that the following questions may be used (as cited in Drake & Burns, 2004):

- ◈ For identifying the purpose and desired results:

- ◆ What is worthy and required for understanding?

- ◆ How will students be different at the end of the unit?

- ◈ For reviewing the standards to determine how to use them in an interdisciplinary framework:

- ◆ Can standards be organized in meaningful ways that cut across the curriculum?

- ◈ For securing acceptable proof of learning:

- ◆ What is evidence of understanding?

- ◈ For deciding the experiences that lead to desired results:

- ◆ What learning experiences promote understanding and lead to desired results? (p. 33)

Benjamin Bloom's Taxonomy

Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy has been use as a cognitive hierarchical structure of higher order thinking since the mid-1950s to create assessments, develop courses, plan lessons, evaluate the complexity of assignments, and establish project-based learning. Bloom classified the criteria from lowest to highest: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Bloom’s taxonomy centers o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Concept-Based Unit Design: Leading Instructional Philosophies

- Chapter 2 Mapping the Cross-Curricular Year

- Chapter 3 Creating Rich Learning Experiences,Transfers, and Application

- Chapter 4 Deepen and Focus: Essential Questions and Enduring Understandings

- Chapter 5 Putting It All Together: A Sample Unit

- References

- Appendix Planning Templates

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Concept-Based Instruction by Brian Scott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.