eBook - ePub

Promoting Rigor Through Higher Level Questioning

Practical Strategies for Developing Students' Critical Thinking

- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Promoting Rigor Through Higher Level Questioning

Practical Strategies for Developing Students' Critical Thinking

About this book

Promoting Rigor Through Higher Level Questioning equips teachers with effective questioning strategies and:

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Getting Started With Higher Level Questioning

DOI: 10.4324/9781003237372-2

Essential Question: How can you use higher level questioning to make your classroom more rigorous?

Socrates is considered by many to be one of the greatest thinkers in history. He wrestled with philosophical topics such as morality, virtue, knowledge, and politics. He is well-known for the Socratic method, a form of cooperative dialogue that is based on asking questions until participants arrive at the truth. In order to arrive at the truth, you have to ask the right questions, building upon the answers to formulate additional questions. This is what it looks like if I were having a conversation with my youngest daughter:

My daughter: “I just love dogs.”

Me: “What is it about dogs that you love so much?”

My daughter: “They’re so cute.”

Me: “What, specifically, is so cute about them?”

My daughter: “They’re so soft.”

Me: “So you like the soft coat of a dog. What about dogs with coarser coats, such as a poodle or a bulldog?”

My daughter: “No, I love them, too.”

Me: “Maybe it’s not their softness that makes you love dogs so much. Maybe it’s something else?”

My daughter: “I suppose it could be.”

Me: “What is the first thing you notice when you see a dog?”

My daughter: “Its tongue.”

Me: “What about its tongue?”

My daughter: “How it hangs out of its mouth like it’s smiling.”

Me: “So you like dogs’ tongues?”

My daughter: “I like when they lick me with them. It shows me they love me.”

Me: “Are you saying that what you enjoy is that dogs show love so much?”

My daughter: “Yes, that is what I love about dogs.”

This conversation took a little while, but with some persistent questioning, we arrived at a much deeper response than simply that my daughter loves dogs. In the examination, she discovered why she loves dogs so much. At first she thought it was their softness, but with further questioning, she realized that was not accurate. She really just loves that dogs are extremely loving, and she was able to associate that with their tongues.

This method can be used with much weightier issues. Take this conversation, for instance, between a mother and son:

Son: “I’m afraid of death.”

Mother: “What about death is so frightening?”

Son: “That you’re no longer here, that you’re somewhere else.”

Mother: “And you don’t think that somewhere else is going to be a good place?”

Son: “I would like to hope it is.”

Mother: “But you’re not sure?”

Son: “No, I’m not sure.”

Mother: “What if you knew that it was a good place?”

Son: “Then it probably wouldn’t seem so bad.”

Mother: “And you wouldn’t be as afraid?”

Son: “Probably not.”

Mother: “What I’m hearing you say is that you aren’t afraid of actual death; you’re afraid because you don’t know what happens after death. Is that correct?

Son: “Yes, I suppose that is.”

Mother: “So your fear is more about the unknown?”

Son: “Yes, that is my fear.”

This conversation involves a much heftier topic than the conversation I had with my daughter, but the takeaway is similar. Someone states something, and through a series of questions designed to explore the topic further, you arrive at something much deeper. You understand not only the “what,” but also, more importantly, the “why.”

This type of questioning can be applied to more than philosophical issues. Consider this conversation in an elementary math classroom, in which a student has not yet learned subtraction:

Student: “The answer is 14.”

Teacher: “And how did you arrive at that answer?”

Student: “I don’t know.”

Teacher: “But you do know because you got the answer correct. How did you do that?”

Student: “I added the two numbers, 8 and 6, together, and they equal 14.”

Teacher: “How did you know to add the numbers?”

Student: “There was the plus sign between the numbers.”

Teacher: “What if there had been a minus sign in its place?”

Student: “Then I would have gotten a different answer.”

Teacher: “Why is that?”

Student: “Because in addition you add the numbers together, and when there is a minus you subtract one from the other.”

Teacher: “Why does that make the answers different?”

Student: “Because in addition the answer is always greater than the numbers used in the problem.”

Teacher: “And how is this different with subtraction? Is the number not bigger when you subtract?”

Student: “No.”

Teacher: “What is it?”

Student: “It’s smaller.”

Teacher: “Why does it become smaller?”

Student: “Because you are taking one number away from the other.”

Teacher: “Which makes it smaller?”

Student: “Yes.”

Teacher: “What would the smaller number be if the problem was 8 – 6?”

Student: “I don’t know.”

Teacher: “But you do. You said you take the number away from the other. When you take 6 away from 8, what is left?”

Student: “2.”

Teacher: “Great. Is it smaller than both numbers?”

Student: “Yes.”

Teacher: “Does it always have to be smaller than both of the numbers?”

Student: “I think so.”

Teacher: “What if we took 8 and subtracted 2? What would be left?”

Student: “6.”

Teacher: “Is that smaller than both numbers?”

Student: “No, just the first one.”

Teacher: “So we can assume that in subtraction, the answer is always smaller than the first number.”

Student: “We can.”

Simply by answering some follow-up questions, this student is learning the basic concepts of subtraction, using his prior knowledge of addition to grasp a new concept. These conversations all display the power of higher level questions.

THE BENEFITS OF USING HIGHER LEVEL QUESTIONS IN YOUR CLASSROOM

Are there benefits to using higher level questions with your students? You might think that this question involves an obvious answer. Of course, there are many benefits to using higher level questions in your classroom, but I want to present some of the reasoning behind the importance of higher level questions and thinking. Using higher level questions in your classroom:

- » improves student achievement,

- » builds understanding and retention of learning,

- » increases student engagement,

- » asks students to think for themselves, and

- » teaches valuable 21st-century skills.

IMPROVE STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT

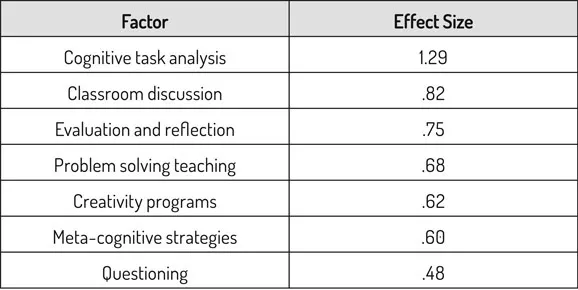

When considering student achievement, the groundbreaking work of Hattie (2018) is a great place to start. Throughout his career, he has looked at many practices and research and determined which factors have the greatest effect on student achievement. Figure 2 shows some of the results for purposes of this discussion (you can see the complete list at https://visible-learning.org/hattie-ranking-influences-effect-sizes-learning-achievement). An effect size above .4 means a factor is effective; anything below that is ineffective. Note that Hattie does not explicitly use the exact phrasing “higher level questioning” as one of the strategies. You will notice that “questioning” is only rated a .48, but the other related factors listed in Figure 2 all employ higher thinking skills. This shows that questioning by itself is mildly effective, but when you ask students the right questions that require them to think at a higher level, such as through cognitive task analysis, evaluation, and creativity, the effect on achievement is much stronger. When you also consider that classroom discussion, a strategy that employs higher level questions, rates at a .82, it becomes even clearer that higher level questions designed to allow students to think are, indeed, an effective practice for improving student achievement.

BUILD UNDERSTANDING AND RETENTION

Higher level questioning helps students gain understanding. If you ask lower level questions, you essentially require them to access the part of their brain that has memorized a term or concept and to duplicate it in the form of an answer. Knowing something and understanding something are completely different. Knowing a concept does not mean students can create with it, adapt it to apply to another concept, or break it down and look at its various components. These are all acts of thinking.

For example, when learning about airplane flight, you might come across the following information:

When air rushes over the curved upper wing surface, it has to travel further than the air that passes underneath, so it has to go faster (to cover more distance in the same time). According to a principle of aerodynamics called Bernoulli’s law, fast-moving air is at lower pressure than slow-moving air, so the pressure above the wing is lower than the pressure below, and this creates the lift that powers the plane upward. (Woodford, 2019, para. 7)

A student might read this information or watch a video on the principles of flight. When the student is asked “How are airplanes able to fly?”, he could recite this definition and be correct. That does not mean that the student understands how flying works. The student may not be able to explain how the lift on a stunt plane flying upside now does not have the opposite effect and instantly send the plane downward. If, however, a student has an understanding of how lift works, he would be able to determine possible solutions to this dilemma.

If the teacher asked, “How are paper airplanes able to fly even though they typically have flat wings that would not be able to produce lift?”, a student who only “knows” the definition would have difficulty making sense of this. The student who understands it might be able to discern that:

paper airplanes are really gliders, converting altitude to forward motion. Lift comes when the air below the airplane wing is pushing up harder than the air above it is pushing down. It is this difference in pressure that enables the plane to fly. Pressure can be reduced on a wing’s surface by making the air move over it more quickly. The wings...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction Rating Your Questioning Behavior

- Chapter 1 Getting Started With Higher Level Questioning

- Chapter 2 The Difference Between Difficulty and Rigor: Changing Your Mindset

- Chapter 3 Building Question Awareness

- Chapter 4 Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to Improve Your Questioning Behavior

- Chapter 5 Moving Questions Into a Higher Level of Thinking

- Chapter 6 Raising the Rigor of Content Standards

- Chapter 7 Writing Rigorous Questions

- Chapter 8 Asking Higher Level Verbal Questions

- Chapter 9 Establishing a Rigorous Classroom Culture

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Promoting Rigor Through Higher Level Questioning by Todd Stanley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.