eBook - ePub

Reluctant Disciplinarian

Advice on Classroom Management From a Softy Who Became (Eventually) a Successful Teacher

This is a test

- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reluctant Disciplinarian

Advice on Classroom Management From a Softy Who Became (Eventually) a Successful Teacher

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this funny and insightful book, Gary Rubinstein relives his own truly disastrous first year of teaching. He begins his teaching career armed only with idealism and romantic visions of teaching—and absolutely no classroom management skills. By his fourth year, he is named "Teacher of the Year." As Rubinstein details his transformation from incompetent to successful teacher, he shows what works and what doesn't work when managing a classroom such as:

- Develop a teacher look. The teacher look says, "There's nothing you can do that I haven't already seen, so don't even bother trying."

- Show students that you are a "real" teacher by doing things they expect of real teachers, at least for a while.

- Be prepared to utter a decisive answer to anything within 2 seconds. Decisive answers inspire confidence.

Any teacher—experienced or not—will enjoy this honest and humorous look at the real world of teaching!

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Reluctant Disciplinarian by Gary Rubinstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Ten Years Later

Things are not always as simple as they seem

DOI: 10.4324/9781003237709-9

Looking back…

It’s been ten years since the publication of this book and nearly twenty since my harrowing first year of teaching. For this new edition, I’ve had the opportunity to reflect again on my experiences as a developing teacher.

Today, I have a different perspective on what happened during those first two years. When I wrote originally, I was still relatively close in time to those first few years and my interpretation was somewhat skewed by what I wanted those years to be like. The way I wrote it, I was too nice my first year, too mean the second year, and then, apparently, “just right” afterwards. Now I have a more realistic view of what it was really like (kind of like looking down from a hot-air balloon; the further away you get, the more you can see.)

Things were a lot more complicated than the picture I painted. My first year was so distressing that, looking back, I’m convinced I suffered from a type of post-traumatic stress disorder. Although I know the experiences aren’t comparable at all, I’ve read memoirs by Vietnam War veterans and found myself thinking, “Been there.” My twenty-year obsession with reliving and trying to undo my first year failure demonstrates that I still haven’t completely gotten over it.

It would take a lot of time and a lot of distance for me to truly escape what I lived through. That’s why, after my fifth year of teaching, I quit.

A new career

In 1996, I left teaching and pursued a degree in computer science. I spent the next five years sitting at a desk talking only to a computer in a language called “C++.”

Programming was the opposite of teaching. I liked the fact that the computers, though often disobedient, never talked back.

Programming was the opposite of teaching. I liked the fact that the computers, though often disobedient, never talked back. If a computer became impossible to work with, I wouldn’t think twice about doing the equivalent of a One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest frontal lobotomy by wiping clean the contents of the hard drive. The best part about being a computer programmer was that, unlike being a teacher, I didn’t have to take anything home with me—not papers, not emotions.

As a beginning computer programmer, I started with one of the most tedious and uncreative assignments. I was a level one debugger for a desktop publishing program. Commercial software, I learned, is generally released with thousands of errors or “bugs.” Though a team of testers tries to find them before the software is shipped, many bugs still slip by. Home users, who pay $500 for the privilege of using the crash-prone programs, locate the remaining bugs and call the company to complain.

When enough calls are logged about the same problem, a debugger is notified. Back then, I’d read the heading of the “bug report”—something like, “Program crashes when you push enter, backspace, and shift at the same time while saving a file.” It was not my place to ask why anyone would ever find themselves doing that, let alone take time to report the bug, but dozens did. The first step in fixing a bug was to make sure it wasn’t a false alarm. I’d push this ridiculous combination of keys in an attempt to crash the program. I always feared that one day I’d see a bug report reading, “Program abruptly closes when user sticks the mouse up his nose.”

If I could successfully crash the program by following the steps, I’d have to comb through a million lines of computer code to fix it. Otherwise, I’d close out the bug with the three-word explanation, “Unable to reproduce.” Ironically, this was also an accurate description of my social life at the time.

When I was a teacher, I was always looking at my watch and thinking, “How did this period go by so quickly?” As a programmer, I would do the opposite.

Not like teaching at all. When I was a teacher, I was always looking at my watch and thinking, “How did this period go by so quickly?” As a programmer, I would do the opposite. Ten times a day, I’d estimate the time and then compare it to the actual time. If the real time was significantly later than the time I thought it was, I’d get a little thrill.

Another way I’d make the time go by more quickly was with something I could never do as a teacher—use the bathroom. At the slightest hint of discomfort, I’d be off to the bathroom for a ten-minute break. On the way back, I’d stop by the cooler and refill my water bottle, in anticipation of my next bathroom break.

Still, I never completely separated myself from teaching. At night, I taught computer programming at a college. Over the summers, I continued volunteering at teacher training programs, presenting the ideas from this book. I was a teacher in a computer programmer’s unstylish clothing.

The main result of my five agonizing years as a debugger was that I became much more marketable. Even though I hated being a computer programmer, I thought that if I could land a job in the financial district of Manhattan, I could at least make a lot of money while hating it.

Moving to Manhattan

Teacher 1991–1996

For five years, I had embraced the Teach For America motto, “All children can learn.”

The words above look more like something carved on a tombstone than a line from a resume. At first, the details of my accomplishments during my five years of teaching dominated my resume. My employment recruiter kept shortening the description of my teaching experience, arguing that it would only hurt my chance of getting an offer to program computers for a Fortune 500 investment firm.

I refused his request that I cut my teaching experience out of the resume altogether, but I compromised by allowing it to become one line. For five years, I had embraced the Teach For America motto, “All children can learn.” I had worked hard to show that, with high expectations, all children not only can but will learn. Just as I would never cut those experiences from my memory, I couldn’t disrespect them by cutting them completely out of my resume.

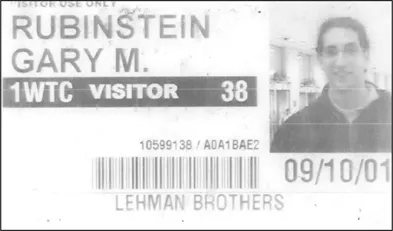

When I moved to New York in August of 2001, my recruiter, Mark, set up a series of job interviews for me. My last interview took place on the 38th floor of the North Tower of the World Trade Center. The date was September 10, 2001. Had they offered me the job and asked how soon I could start, I surely would have said “tomorrow.”

On September 13, two days after the tragic events at the World Trade Center, my headhunter called me. Casually, he asked, “Did you get a chance to write a thank you letter to the people at Lehman Brothers?”

I was incredulous. “Do you really think I should, under the circumstances?” I asked.

“Oh, definitely. Nobody died from that floor. They’ve even set up new headquarters in the Marriott hotel in mid-town.”

My last interview took place on the 38th floor of the North Tower of the World Trade Center. The date was September 10, 2001.

Not knowing what could possibly be appropriate, I wrote an e-mail to the man who had interviewed me: “I was relieved to learn that everyone on the 38th floor evacuated the building safely. I’m not sure if the attacks have changed your need for computer consultants, but I’d like you to know that I really enjoyed our interview and am still eager to work for you.”

He never got back to me.

Teaching of a different kind

September 11 definitely took the momentum out of my new life plan to be a wealthy computer programmer in Manhattan. Just as ten years earlier I hadn’t been able to muster up the energy to complete my law school applications, now I wasn’t actively pursuing computer jobs.

I enjoyed training new teachers and knowing that I was, once again, making a difference, though indirectly.

In early 2002, I learned of a job opening with the New York City Teaching Fellows (NYCTF). NYCTF is a spin-off of the Teach For America program that trained me. While the Teach For America program recruits recent college graduates who want to teach for a few years before pursing other higher-paying careers, NYCTF does the opposite. It recruits people who have already had lucrative jobs and are now ready to become teachers.

I took the teacher training position, and my passion for teaching was instantly renewed. I enjoyed training new teachers and knowing that I was, once again, making a difference, though indirectly. Those twenty teachers would be teaching a total of three thousand kids. By helping them become better teachers, I would help those three thousand kids learn more, without ever meeting them.

One of the connections I made during this time gave my name to Danny Jaye, the math department chair at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan. Stuyvesant had recently been featured on the front page of Newsweek as “The High School At Ground Zero,” since it was located only three blocks from the infamous disaster. A teacher who was concerned about the air quality in the school had requested a transfer, Jaye explained. A man who likes to get right to the point, he asked, “How would you like to teach in the best high school in the city?”

For many teachers, this would be a dream come true. For me, it was a serious dilemma. In my Teach For America years, the low teacher pay was balanced by the knowledge that I was making a difference for some very needy kids. Though some Stuyvesant students were definitely traumatized by their sudden evacuation on September 11, they were not academically needy. I had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to teach at Stuyvesant, the most competitive math and science school in New York City, but deep down I knew I belonged in the low-performing schools in nearby Bedford-Stuyvesant, the area featured in Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing.

Even when you’re not teaching, you’re still a teacher. You’re just a teacher in recovery.

Despite my concerns, I agreed. If nothing else, I figured that the job would be easy. Why I thought that is a mystery.

When I taught before, I had been so obsessed with my work that teaching seemed almost like a drug. I’m sure that when I told my family about my decision, they whispered behind my back, “Oh, God, he’s teaching again.” If you’ve ever been a teacher, you’re always a teacher. It’s like being an alcoholic. Even when you’re not teaching, you’re still a teacher. You’re just a teacher in recovery.

But what concerned me most wasn’t the daunting task of planning lessons, making tests, and grading homework. It was something more practical: Did I still have the ability to “hold it in?” My time-wasting habit of using the bathroom anytime I was bored had completely ruined my former bathroom stamina.

Teaching the “bad kids.” Stuyvesant High School occupied a ten-floor building in downtown Manhattan and was at that time the most expensive school ever built, at about one hundred and fifty million dollars. With marble floors and an Olympic-sized pool, this building had the best of everything. Twenty thousand of the top eighth graders in the five boroughs of Manhattan take the placement exam every November to see which eight hundred will be admitted to this school.

What were the “bad kids” at this prestigious school going to do that was so bad? Carve math equations into their desks with the point of their compasses?

Of my five scheduled classes, three were trigonometry classes and two were something called “advanced algebra.” Though the “advanced” in the t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- The Accidental Teacher

- History of a Softy

- Why Learning to Discipline Is So Hard

- What Does Not Work

- Being a Real Teacher

- What Does Work

- Developing a Teacher Persona

- Answers From Real Teachers

- Ten Years Later