1.Introduction

The goggles throw a light, smoky haze across his eyes and reflect a distorted wide-angle view of a brilliantly lit boulevard that stretches off into an infinite blackness. This boulevard does not really exist; it is a computer rendered view of an imaginary place (Stephenson 1992, 3).

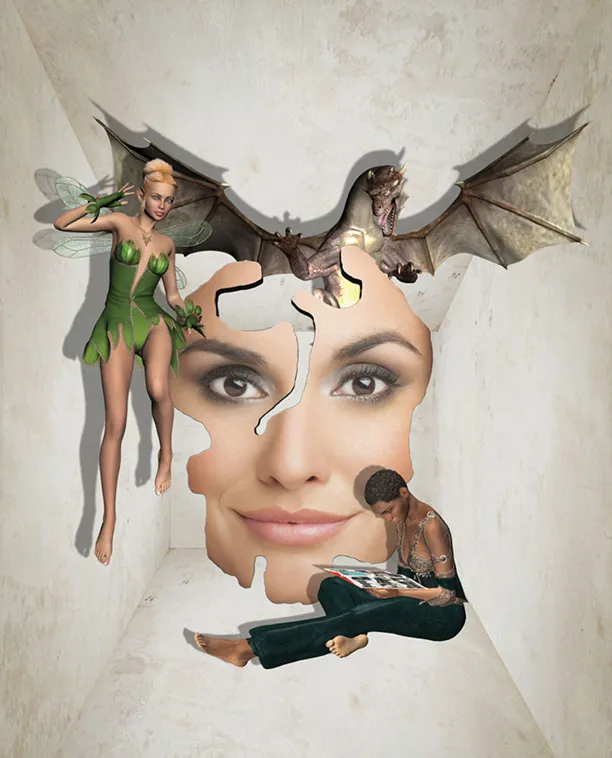

That is an opening scene from Neal Stephenson’s 1992 futurist thriller Snow Crash, a novel that preceded the virtual world Second Life by more than a decade. Now that another decade has passed, Second Life lives on as the longest-running virtual world. Preceding Second Life and instrumental to its development were SimCity (1989), Battle Tech (1990), Cybertown (1995), Active Worlds (1995), EverQuest (1999), Neopets (1999), Habbo (2000), and The Sims (2000); the beta version of Second Life (Linden World) was introduced in August 2001. Other platforms followed (Eve Online, 2003; There, 2003; IMVU, 2004; World of Warcraft, 2004), each catering to its membership in various ways. Second Life, however, has perhaps given the most freedom to its members in terms of design and control of their avatars and creative works. Its world rests upon the principle of user-created content and a community built by its membership (figure 1).

Between the imagination of authors and film directors, and that of scientific achievements (from the 1945 hypertext theoretical prototypes to NASA’s 1985 virtual environment work station to the invention of the Internet soon after), a foundation had been laid for a convergence of imagination, technology and human desire to travel within the inner space. In 1962, Father of Virtual Reality Morton Heilig (2015) made a step toward a full sensory simulation with the Sensorama, complete with smell and motion in a cinema-like arcade room designed for an individual viewer. In the early 1960s, he also patented an early form of Head Mounted Display, and a competing system by Philco Corporation was constructed soon after he proposed his initial idea (Virtual Worlds 2011).

By 1974, Star Trek introduced the Holodeck to its viewers. Now anything seemed possible for humanity, as only one’s imagination appeared the limit. Virtual reality, time travel, and teleportation were visualized in millions of homes as revelation. Other contributors to virtual reality can be credited to the special effects professionals of the motion picture industry. Computer Generated Imagery (CGI) was possible through the ingenuity of Industrial Light and Magic, the legendary company founded by filmmaker George Lucas in 1975. By 1989, Autodesk would demonstrate William Gibson’s (1984) concept of cyberspace through computer simulation and aspects of virtual reality popularized by his book Neuromancer. For other pivotal events, see the following timelines: The History of Virtual Worlds (2010) and Virtual Worlds (2011). The high-end graphics of games and animation would propel interest in furthering advances in software. The public was interested increasingly in participating and experiencing games, simulations, and a sense of virtual reality. Second Life members have incorporated many of these ideas into their builds, role play, art, films, and discussions over the years.

Thomas Malaby (2009), for Making Virtual Worlds: Linden Lab and Second Life, interviewed Linden Lab/Second Life founder Phillip Rosedale, who revealed science fiction and notably Snow Crash as his inspiration. Stephenson’s character Hiro Protagonist is as ordinary as many of the members in Second Life. He is a delivery pizza man in his routine real life. But his true calling as a computer hacker, rooted in his alternate meta-existence, is what will define him as a person. As his avatar ventures deep within the virtual rabbit hole seeking out the deadly viral drug Snow Crash, a new world is disclosed that calls question to the meaning of life. Once a person assumes his or her avatar body, boundaries are blurred, and what happens virtually impacts reality. The book is pivotal to not only the making of Second Life, but still to the in-world community whose membership occasionally pays homage to the plot in their artistic installations. The virtual body becomes the means toward self-actualization. Hiro leans on his cultural background and his computer savvy to rise above the circumstances. Perhaps this becomes the basis for understanding the appeal of Second Life, where the motivation is to experiment and extend one’s opportunities beyond normalcy. What might not seem possible in real life becomes the premise for a new beginning in the virtual. In Second Life, Media and The Other Society, I acknowledge the difficulty of trying to understand the platform without first having become an avatar, flying through a virtual sunset, swimming in a magnificent blue ocean without getting wet, building the home of your dreams, walking through a Van Gogh painting or a Ray Bradbury book, attending a physics lecture as a troll, and making friends across the world (Johnson 2010, xiii).

The virtual realm is not easily framed, without enduring considerable conceptual challenges, contextualization and debate among scholars. One of the leading authors Howard Rheingold reported on the first virtual communities of the Internet; his studies are grounded with a media over scientific perspective. Rheingold (2000), in The Virtual Community, centers his views within the mediated hub, that of the early Internet which brought people together to share issues and themes through community building. This becomes a tale of media empowerment via long awaited human connectivity, albeit slow modems at the time. The imagery is that of text, and the people behind the words contribute to the collective sense of community that emanates from the experience. Rheingold (2000, 8) acknowledges the »seed of truth« behind cautionary words »decrying the circumstances that lead some people into such pathetically disconnected lives that they prefer to find their companions on the other side of a computer screen,« inserting that »virtual communities require more than words on a screen at some point if they intend to be other than ersatz.« He cites his own experiences, as well as others, as examples of support and information found within his virtual community, The Well, with interaction extending into real life gatherings initiated by bonds formed first online.

One might speculate that the participants perceived strength and fellowship from the experience, and then that carried over into their real life, interpreted within their life experiences and memories. One might also simply ask how the written words of a poem or story engaged its readers; is it not because of the imagery and other senses enacted during the process, connecting and assigning past emotions and meanings to new thoughts? The theater of the mind as a stage is a worthy component of virtual reality. Rheingold (2000, 8) states:

Those who critique CMC [Computer Mediated Communication] because some people use it obsessively hit an important target, but miss a great deal more when they don’t take into consideration people who use the medium for genuine human interaction.

2.The Author as Virtual Participant

In this discussion, I draw from more than eight years of virtual experience, nearly on a daily basis, within Second Life in the role of educator, virtual journalist, one-time fashion designer, photographer, machinimatographer, radio dj, and many other roles – but all under the persona of one avatar – Sonicity Fitzroy. I have written two books related to my virtual life, particularly as it relates to media in the virtual world. Authors like Tom Boellstorff (2010) in Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human and Wagner James Au (2008) in The Making of Second Life have shared their experiences and thoughts on identity in Second Life. The avatars of Boellstorff and Au are long-time residents and experts of Second Life. Boellstorff et al. (2012) outlines research methods for the cultural study of virtual worlds in Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Among the means of data collection, the authors note participant observation, in-world interviews, chatlogs, screenshots, video, audio, virtual artifacts, and historical and archival research. Capturing life in Second Life is relatively easy for many members like to share their experiences through online forums and photo and video galleries, at least for those who don’t mind the virtual spotlight.

Others prefer anonymity. The AVI Choice Awards is an annual ceremony since 2011 recognizing the contributions of avatars across numerous categories – from fashion, music to media. It serves as sign and reminder that the people behind the avatars strive for recognition among their peers as in real life. The avatar is a creation in Second Life, as is all the components that comprise its virtual world, and contributions are honored as a service and symbol that life extends online.

Aside from the wonderful creations in Second Life, life is fairly ordinary, with people chatting, dancing and working together on projects. There are moments of isolation, if one so wishes. There are role play communities, in which one can play a character of his or her invention. Some have multiple avatars that reflect their unique interests. Each of the avatars arguably holds a piece of its source’s human soul, and varying characteristics are revealed upon interaction with others. It is often through others that participants understand themselves. Some avatars become celebrities, such as famous ...