eBook - ePub

Social, Emotional, and Psychosocial Development of Gifted and Talented Individuals

This is a test

- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social, Emotional, and Psychosocial Development of Gifted and Talented Individuals

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Social, Emotional, and Psychosocial Development of Gifted and Talented Individuals:

- Merges the fields of individual differences, developmental psychology, and educational psychology with the field of gifted education.

- Provides a complete overview of the social, emotional, and psychosocial development of gifted and talented individuals.

- Explores multiple paradigmatic lenses and varying conceptions of giftedness.

- Serves as a comprehensive resource for graduate students, early career scholars, and teachers.

- Addresses implications for the field of gifted education and future research.

This book is framed around four broad questions: (a) What is development?, (b) Are gifted individuals qualitatively different from others?, (c) Which psychosocial skills are necessary in the development of talent?, and (d) What effect does the environment have on the development of talent? Topics covered include developmental trajectories, personality development, social and emotional development, perfectionism, sensory sensitivity, emotional intensity, self-beliefs, motivation, systems perspective, psychosocial interventions, and counseling and mental health.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Social, Emotional, and Psychosocial Development of Gifted and Talented Individuals by Anne Rinn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Inclusive Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Background

DOI: 10.4324/9781003238058-2

Do gifted individuals have unique characteristics that render them particularly vulnerable to an array of social and emotional difficulties? Do “the characteristics associated with giftedness … make the subjective experience of meeting normal challenges qualitatively different from others’ experience” (Peterson, 2009, p. 281)? Or, are gifted individuals socially and emotionally similar to average-ability individuals? Are the social and emotional difficulties some gifted individuals face due to interaction with an environment that does not facilitate the development of their talents? Does one’s definition of giftedness impact how one answers these questions?

For hundreds of years, the general belief among most people was that highly intelligent individuals were doomed to lives of social isolation, emotional instability, and psychopathology (Lombroso, 1891). However, with the Scientific Revolution, “a paradigm of demystification of giftedness emerged, in which scientists and scholars strived to unpack individual differences through systematic investigation and measurement” (Lo & Porath, 2017, p. 345). Simultaneous attempts at defining intelligence and measuring intelligence resulted in the first iteration of the modern-day IQ test in the early 1900s (Binet & Simon, 1904), as well as the notions of intelligence and human ability as IQ-based, an approach that has prevailed for more than a century. The IQ test allowed Terman (1925), the father of gifted education, a way to identify and label a group of high-ability children for his longitudinal study, resulting in the operationalization of giftedness as a high IQ.

Terman (1925) was the first to challenge beliefs from the late 1800s regarding highly intelligent individuals having social and emotional difficulties in his longitudinal study of 1,528 children with IQs above 140. Terman and his colleagues found that gifted children were average in many respects, including social adjustment and emotional stability. He concluded that gifted individuals were not doomed to poor social and emotional experiences throughout life, but that gifted individuals led satisfying and fulfilling lives. Critics of Terman’s work pointed out that the children in his study were all identified as intellectually gifted by their teachers, and there was very little ethnic, racial, or economic diversity in his sample. The generally positive adjustment found among these gifted children may not have been found among similarly able children who were not selected for Terman’s study, as the selected children were perhaps already well-adjusted because of the economic resources and stability of their families (Gross, 2004; Vialle, 1994). Other criticisms surrounding Terman’s work include “an overemphasis on IQ, support for the meritocracy, and emphasizing genetic explanations for the origin of intelligence differences over environmental ones,” as well as his “willingness to form a strong opinion based on weak data” (Warne, 2019, p. 3). Despite these criticisms, Terman’s work was influential and changed the way highly intelligent individuals are viewed, particularly with regard to their social and emotional development.

Hollingworth (1926, 1942) also made significant contributions to the understanding of the social and emotional development of gifted individuals. Hollingworth examined the peer relationships of children at differing ranges of intellectual giftedness, also using the newly developed IQ test to operationalize giftedness. She conducted her research in public school classrooms and discovered differences in the cognitive and affective development of moderately (IQ = 125–155) and highly (IQ > 160) gifted children. Moderately gifted children were found to be socially well-adjusted and self-confident, but the highly gifted children struggled with social isolation because of difficulties finding intellectual peers (Hollingworth, 1926). Yet, when these highly gifted children were permitted to work and play with their intellectual peers, regardless of chronological age, their social isolation largely disappeared (Gross, 2004).

Both Terman (1925) and Hollingworth (1926) set the stage for the study of the social and emotional development of gifted individuals, which continues today. Contemporary approaches to studying the social and emotional development of gifted children and adolescents are varied; most research focuses either on factors that might place gifted students uniquely at risk for social and emotional difficulties (Neihart et al., 2015) or on those psychosocial factors that might enhance the development of talent (Rinn, 2012). These two approaches to studying the social, emotional, and psychosocial development of the gifted can be somewhat aligned with the paradigmatic approach to giftedness that a researcher takes.

On the one hand, when approaching the notion of giftedness as that of a high IQ (e.g., IQ > 130), per Terman (1925) and Hollingworth (1926), asynchronous development among gifted individuals is observed, whereby the advanced intellectual capabilities of a child—as compared to the typical developmental trajectories related to physical, social, and emotional milestones—result in social and emotional issues unique to the gifted population (The Columbus Group, 1991). In other words, social and emotional issues and vulnerabilities arise because of this asynchronous developmental pattern between intellectual or cognitive abilities and social, emotional, and physical development. As with typically developing populations, intellectual/cognitive development and social, emotional, and physical development are intertwined among the gifted, and uneven rates of development may be impactful:

Emotions cannot be treated separately from intellectual awareness or physical development. All three intertwine and influence each other. A gifted 5-year-old does not function or think like an average 10-year-old. He does not feel like an average 10-year-old, nor does he feel like an average 4- or 5- year old. Gifted children’s thoughts and emotions differ from those of other children, and as a result, they perceive and react to their world differently. (Roeper, 1995, p. 74)

Researchers and practitioners who explicitly focus on the whole child (meaning the cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development) and who believe gifted children are cognitively, socially, and emotionally different from average-ability children have paradigmatic beliefs that align with the gifted child paradigm (Dai & Chen, 2014). The major tenets of the gifted child paradigm are that giftedness is based on IQ or ability level, that ability level can be measured and quantified (via IQ tests or ability measures), that gifted children are a distinct category with unique social and emotional needs, that gifted children should be educated differently than average-ability children, and that “once gifted, always gifted” (p. 48). Evidence of the impact of these unique paradigmatic beliefs will be shown throughout this book, despite the shifts in the operationalization of giftedness that began in the mid-1900s.

In the mid-1900s, the notion of giftedness expanded to include more than just IQ or general ability. For example, Witty (1958) distinguished between general intellectual abilities and specific talents, and Guilford (1950) drew attention to the construct of creativity. In 1972, the federal definition of giftedness comprised multiple categories, only two of which included intellectual or academic ability:

Children capable of high performance include those with demonstrated achievement and/or potential ability in any of the following areas, singly or in combination:

- General intellectual ability

- Specific academic aptitude

- Creative or productive thinking

- Leadership ability

- Visual and performing arts

- Psychomotor ability (Marland, 1972, p. 2)

The 1980s and 1990s saw numerous definitions of intelligence that emerged in the research literature and in popular psychology that included multiple categories and ways to be intelligent (Gardner, 1983/2011; Sternberg, 1985, 1986), and a new type of intelligence called emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1995; Salovey & Mayer, 1990). A new paradigmatic approach to understanding the notion of high ability had emerged.

If giftedness is viewed as something broader than just high IQ (e.g., as advanced academic abilities or domain-specific talents), a focus on unique social and emotional issues among the gifted becomes somewhat irrelevant because the group included as “gifted” is much larger in this operationalization of giftedness. Giftedness based only on a high IQ includes less than 3% of the population, who may have unique social and emotional experiences, as later chapters of this book will explore. But giftedness based on domain-specific abilities comprises a much larger group of people that is even less homogenous than those in the top 3% of the normal distribution, and it becomes more difficult to pinpoint unique social and emotional experiences with such a diverse group of people. Instead, when focusing on domain-specific talents, there is a tendency to focus on the development of an individual’s psychosocial skills that could impact the pursuit of expertise or eminence in that domain, such as persistence, goal-directed behavior, and self-beliefs.

Researchers and practitioners who focus on the circumstances in which talent develops within an individual have paradigmatic beliefs that align with the talent development paradigm (Dai & Chen, 2014). With regard to the affective component of the talent development model, in particular, there is a focus on “the deliberate cultivation of psychosocial skills rather than simply identification of traits within individuals” (Olszewski-Kubilius et al., 2015b, p. 196), meaning a focus on psychosocial skills such as goal-directed behavior will be more beneficial for developing talent than a focus on social and emotional traits like sensory sensitivity or emotional intensity. Depending on the researcher’s paradigmatic perspective, then, there are implications regarding the definitions of giftedness and talent, gifted education, and social, emotional, and psychosocial development. Dai and Chen (2014) explained,

Practical concerns and theory-driven research regarding the role of affect in talent development are quite different from those researchers whose focus is on social-emotional issues as an inherent part of being gifted; the latter has been a more dominant theme in research … Although being gifted and talented can correlate with particular social and emotional problems … affect in the context of talent development is more of a developmental issue: how certain affective experiences facilitate versus inhibit personal agency and initiative and foster versus impede a particular developmental path. (p. 165)

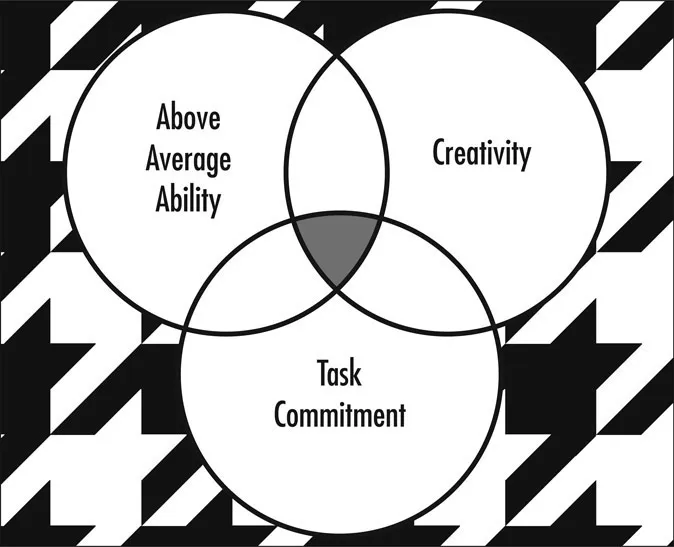

The shift from the gifted child paradigm to the talent development paradigm has caused disagreement among those in the field of gifted education for decades. This paradigmatic competition can be viewed from a timeline perspective. Following the publication of the federal definition of giftedness (Marland, 1972), Renzulli (1978) outlined his Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness (see Figure 1), which identified three interacting clusters of traits that also interact with personality and the environment to result in gifted behaviors. The three traits are: (a) above-average ability, but not necessarily superior ability (as measured by a cognitive ability or achievement test); (b) task commitment, which is a form of motivation; and (c) creativity, or curiosity and imagination.

Note. The houndstooth background represents personality and environment, factors that give rise to the three clusters of traits. This background was not in the 1978 visual depiction of the Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness and was added later. From “Schools Are Places for Talent Development: Promoting Creative Productive Giftedness,” by J. S. Renzulli and S. M. Reis, in J. A. Plucker, A. N. Rinn, and M. C. Makel (Eds.), From Giftedness to Gifted Education: Reflecting Theory in Practice (p. 22), 2017, Taylor & Francis. Copyright 2017 by Taylor & Francis. Reprinted with permission.

The Columbus Group (1991) drafted its definition of giftedness as asynchronous development in direct response to Renzulli’s (1978) focus on gifted behaviors rather than the gifted child (discussed in detail in Chapter 2). Betts (1986) developed his Autonomous Learner Model, which is programming designed to focus on the whole gifted child, including the physical (health) domain, the intellectual/cognitive domain, the social domain, and the emotional domain (discussed in detail in Chapter 10). The Columbus Group’s (1991) definition of giftedness as asynchronous development and Betts’s Autonomous Learner Model (1986), both decidedly in the gifted child paradigm, were followed by a wave of talent development models: Tannenbaum’s (1983) talent development model consists of five components, all of which must be in place in order for giftedness to develop into performance or production during adulthood. The components are general ability (g), special or domain-specific ability, psychosocial abilities, external support, and chance. Other models of talent development by Coleman (1985), Bloom (1985), and Piirto (2007) followed.

Gagné’s (1985, 2017) Differentiated (now called Differentiating) Model of Giftedness and Talent attempted to distinguish between giftedness and talent in order to reconcile some of the confusion in the field. Gagné (2017) defined giftedness and talent as the following:

Giftedness designates the possession and use of biologically anchored and informally developed outstanding natural abilities or aptitudes (called gifts), in at least one ability domain, to a degree that places an individual at least among the top 10% of age peers.Talent designates the outstanding mastery of systematically developed competencies (knowledge and skills) in at least one field of human activity to a degree that places an individual at least among the top 10% of “learning peers” (those having accumulated a similar amount of learning time from either current or past training). (p. 152)

Gagné merged this model with another of his models to form the Integrative Model of Talent Development (see Chapter 9), but he still differentiated between giftedness and talent, and confusion still exists in the field as it did a couple of decades ago. In 1997, Silverman wrote,

The field has lost its psychological roots and is currently adrift in a sea of confusion. Is giftedness simply a social construction? Is it adult achievement? Can one only be “potentially gifted” in childhood? Should we forget about giftedness and try to develop talents in all children? From the perspective of asynchronous development, the answers to all of these questions is a resounding “No.” These children are at serious risk for alienation if we do not begin to recognize their unique needs in early childhood and support their developmental differences. (p. 55)

The turn of the century saw a renewed focus on talent development. Cross and Coleman (2005) outlined their school-based conception of giftedness, wherein they argued that giftedness is developed capacity in a specific domain of talent. This developed capacity is to an extent dependent upon contexts that support learning and development in a relevant domain, but also dependent upon “traits of the individual student, such as motivation and perseverance” (p. 62). Subotnik et al. (2011; see Chapter 9) presented their Talent Development Megamodel and defined giftedness as follows:

Giftedness is the manifestation of performance or production that is clearly at the upper end of the distribution in a talent domain even relative to that of other high-functioning individuals in that domain. Further, giftedness can be viewed as developmental, in that in the beginning stages, potential is the key variable; in later stages, achievement is the measure of giftedness; and in fully developed talents, eminence is the basis on which this label is granted. Psychosocial variables play an essential role in the manifestation of giftedness at every developmental stage. Both cognitive and psychosocial variables are malleable and need to be deliberately cultivated. (p. 7)

Subotnik et al. (2018) noted the transition from potential to eminence as beginning and end points, respectively, on a continuum of the notion of giftedness. They defined talent development as all that is involved in supporting the transition from potential to eminence. Subotnik et al.’s (2011) presentation of their Talent Development Megamodel led to a special issue of Gifted Child Quarterly (Plucker, 2012) that allowed for numerous responses (some positive and some less so) to the model by top scholars in the field of gifted education. Around that time, the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) created separate task forces to examine research on and implications of the gifted child paradigm and the talent development paradigm, respectively. Most recently, the NAGC Definition Task Force (2018) was created with the goal of revising NAGC’s definition of giftedness an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Background

- Section I: What Is Development?

- Section II: Are Gifted Individuals Qualitatively Different From Nongifted Individuals?

- Section III: Which Psychosocial Skills Are Necessary in the Development of Talent?

- Section IV: What Effect Does the Environment Have on the Development of Psychosocial Skills Conducive to the Development of Talent?

- Concluding Thoughts and Future Directions

- References

- About the Author