This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

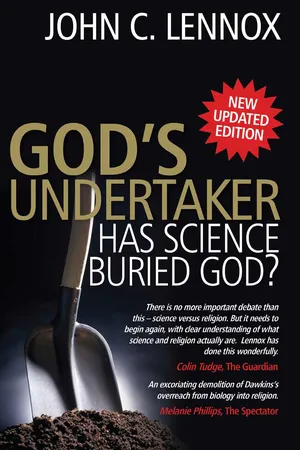

About This Book

If we are to believe many modern commentators, science has squeezed God into a corner, killed and then buried him with its all-embracing explanations. Atheism, we are told, is the only intellectually tenable position, and any attempt to reintroduce God is likely to impede the progress of science.

In this stimulating and thought-provoking book, John Lennox invites us to consider such claims very carefully.

This book evaluates the evidence of modern science in relation to the debate between the atheistic and theistic interpretations of the universe, and provides a fresh basis for discussion. The chapters include:

- War of the worldviews

- The scope and limits of science

- Reduction, reduction, reduction...

- Designer universe

- Designer biosphere

- The nature and scope of evolution

- The origin of life

- The genetic code and its origin

- Matters of information

- The monkey machine

- and, The origin of information.

Now updated and expanded, God's Undertaker is an invaluable contribution to the debate about science's relationship to religion.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access God's Undertaker by John C Lennox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion & Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

War of the worldviews

‘Science and religion cannot be reconciled.’

Peter Atkins

‘All my studies in science… have confirmed my faith.’

Sir Ghillean Prance FRS

‘Next time that somebody tells you that something is true, why not say to them: “What kind of evidence is there for that?” And if they can’t give you a good answer, I hope you’ll think very carefully before you believe a word they say.’

Richard Dawkins FRS

The last nail in God’s coffin?

It is a widespread popular impression that each new scientific advance is another nail in God’s coffin. It is an impression fuelled by influential scientific thinkers. Oxford Chemistry Professor Peter Atkins writes: ‘Humanity should accept that science has eliminated the justification for believing in cosmic purpose, and that any survival of purpose is inspired only by sentiment.’1 Now, how science, which is traditionally thought not even to deal with questions of (cosmic) purpose, could actually do any such thing is not very clear, as we shall later see. What is very clear is that Atkins reduces faith in God at a stroke, not simply to sentiment but to sentiment that is inimical to science. Atkins does not stand alone. Not to be outdone, Richard Dawkins goes a step further. He regards faith in God as an evil to be eliminated: ‘It is fashionable to wax apocalyptic about the threat to humanity posed by the AIDS virus, “mad cow” disease and many others, but I think that a case can be made that faith is one of the world’s great evils, comparable to the smallpox virus but harder to eradicate. Faith, being belief that isn’t based on evidence, is the principal vice of any religion.’2

More recently, faith, in Dawkins’ opinion, has graduated (if that is the right term) from being a vice to being a delusion. In his book The God Delusion3 he quotes Robert Pirsig, author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: ‘When one person suffers from a delusion, it is called insanity. When many people suffer from a delusion, it is called Religion.’ For Dawkins, God is not only a delusion, but a pernicious delusion.

Such views are at one extreme end of a wide spectrum of positions and it would be a mistake to think that they were typical. Many atheists are far from happy with the militancy, not to mention the repressive, even totalitarian overtones of such views. However, as always, it is the extreme views that receive public attention and media exposure with the result that many people are aware of those views and have been affected by them. It would, therefore, be folly to ignore them. We must take them seriously.

From what he says it is clear that one of the things that has generated Dawkins’ hostility to faith in God is the impression he has (sadly) gained that, whereas ‘scientific belief is based upon publicly checkable evidence, religious faith not only lacks evidence; its independence from evidence is its joy, shouted from the rooftops’.4 In other words, he takes all religious faith to be blind faith. Well, if that is what it is, perhaps it does deserve to be classified with smallpox. However, taking Dawkins’ own advice we ask: Where is the evidence that religious faith is not based on evidence? Now, admittedly, there unfortunately are people professing faith in God who take an overtly anti-scientific and obscurantist viewpoint. Their attitude brings faith in God into disrepute and is to be deplored. Perhaps Richard Dawkins has had the misfortune to meet disproportionately many of them.

But that does not alter the fact that mainstream Christianity will insist that faith and evidence are inseparable. Indeed, faith is a response to evidence, not a rejoicing in the absence of evidence. The Christian apostle John writes in his biography of Jesus: ‘These things are written that you might believe…’5 That is, he understands that what he is writing is to be regarded as part of the evidence on which faith is based. The apostle Paul says what many pioneers of modern science believed, namely, that nature itself is part of the evidence for the existence of God: ‘For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities – his eternal power and divine nature – have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that men are without excuse.’6 It is no part of the biblical view that things should be believed where there is no evidence. Just as in science, faith, reason and evidence belong together. Dawkins’ definition of faith as ‘blind faith’ turns out, therefore, to be the exact opposite of the biblical one. Curious that he does not seem to be aware of the discrepancy. Could it be as a consequence of his own blind faith?

Dawkins’ idiosyncratic definition of faith thus provides a striking example of the very kind of thinking he claims to abhor – thinking that is not evidence based. For, in an exhibition of breathtaking inconsistency, evidence is the very thing he fails to supply for his claim that independence of evidence is faith’s joy. And the reason why he fails to supply such evidence is not hard to find – there is none. It takes no great research effort to ascertain that no serious biblical scholar or thinker would support Dawkins’ definition of faith. Francis Collins says of Dawkins’ definition that it ‘certainly does not describe the faith of most serious believers in history, nor of most of those in my personal acquaintance’.7

Collins’ point is important for it shows that the New Atheists, in rejecting all faith as blind faith, are seriously undermining their own credibility. As John Haught says: ‘Even one white crow is enough to show that not all crows are black, so surely the existence of countless believers who reject the new atheists’ simplistic definition of faith is enough to place in question the applicability of their critiques to a significant section of the religious population.’8

Alister McGrath9 points out in his recent highly accessible assessment of Dawkins’ position that Dawkins has signally failed to engage with any serious Christian thinkers whatsoever. What then should we think of his excellent maxim: ‘Next time that somebody tells you that something is true, why not say to them: “What kind of evidence is there for that?” And if they can’t give you a good answer, I hope you’ll think very carefully before you believe a word they say’?10 One might well be forgiven for giving in to the powerful temptation to apply Dawkins’ maxim to himself – and not believe a word that he says.

But Dawkins is not alone in holding the erroneous notion that faith in God is not based on any kind of evidence. Experience shows that it is relatively common among members of the scientific community, even though it may well be formulated in a somewhat different way. One is often told, for example, that faith in God ‘belongs to the private domain, whereas scientific commitment belongs to the public domain’, that ‘faith in God is a different kind of faith from that which we exercise in science’ – in short, it is ‘blind faith’. We shall have occasion to look at this issue more closely in chapter 4 in the section on the rational intelligibility of the universe.

First of all, though, let us get at least some idea of the state of belief/unbelief in God in the scientific community. One of the most interesting surveys in this regard is that conducted in 1996 by Edward Larsen and Larry Witham and reported in Nature.11 For their survey was a repeat of a survey done in 1916 by Professor Leuba in which 1,000 scientists (chosen at random from the 1910 edition of American Men of Science) were asked whether they believed both in a God who answered prayer and in personal immortality – which is, be it noted, much more specific than believing in some kind of divine being. The response rate was 70 per cent of whom 41.8 per cent said yes, 41.5 per cent no and 16.7 per cent were agnostic. In 1996, the response was 60 per cent of whom 39.6 per cent said yes, 45.5 per cent no and 14.9 per cent12 were agnostic. These statistics were given differing interpretations in the press on the half-full, half-empty principle. Some used them as evidence of the survival of belief, others of the constancy of unbelief. Perhaps the most surprising thing is that there has been relatively little change in the proportion of believers to unbelievers during those eighty years of enormous growth in scientific knowledge, a fact that contrasts sharply with prevailing public perception.

A similar survey showed that the percentage of atheists is higher at the top levels of science. Larsen and Witham showed in 199813 that, among the top scientists in the National Academy of Sciences in the USA who responded, 72.2 per cent were atheists, 7 per cent believed in God and 20.8 per cent were agnostics. Unfortunately we have no comparable statistics from 1916 to see if those proportions have changed since then or not, although we do know that over 90 per cent of the founders of the Royal Society in England were theists.

Now how one interprets such statistics is a complex matter. Larsen, for instance, also found that for income levels above $150,000 per year, belief in God falls off significantly, a trend not noticeably limited to those of the scientific fraternity.

Whatever the implications of such statistics may be, surely such surveys provide evidence enough that Dawkins may well be right about the difficulty of accomplishing his rather ominously totalitarian-sounding task of eradicating faith in God among scientists. For, in addition to the nearly 40 per cent of believing scientists in the general survey, there have been and are some very eminent scientists who do believe in God – notably Francis Collins, the current Director of the Human Genome Project, Professor Bill Phillips, winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1997, Sir Brian Heap FRS, former Vice-President of the Royal Society, and Sir John Houghton FRS, former Director of the British Meteorological Office, co-Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and currently Director of the John Ray Initiative on the Environment, to name but a few.

Of course our question is not going to be settled by statistics, however interesting they may be. Certainly the confessed faith in God even of eminent scientists does not seem to have any modulating effect on the strident tones used by Atkins, Dawkins and others as they orchestrate their war against God in the name of science. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that they are convinced, not so much that science is at war with God, but that the war is over and science has gained the final victory. The world simply needs to be informed that, to echo Nietzsche, God is dead and science has buried him. In this vein Peter Atkins writes: ‘Science and religion cannot be reconciled, and humanity should begin to appreciate the power of its child, and to beat off all attempts at compromise. Religion has failed, and its failures should stand exposed. Science, with its currently successful pursuit of universal competence through the identification of the minimal, the supreme delight of the intellect, should be acknowledged king.’14 This is triumphalist language. But has the triumph really been secured? Which religion has failed, and at what level? Although science is certainly a delight, is it really the supreme delight of the intellect? Do music, art, literature, love and truth have nothing to do with the intellect? I can hear the rising chorus of protest from the humanities.

What is more, the fact that there are scientists who appear to be at war with God is not quite the same thing as science itself being at war with God. For example, some musicians are militant atheists. But does that mean music itself is at war with God? Hardly. The point here may be expressed as follows: Statements by scientists are not necessarily statements of science. Nor, we might add, are such statements necessarily true; although the prestige of science is such that they are often taken to be so. For example, the assertions by Atkins and Dawkins, with which we began, fall into that category. They are not statements of science but rather expressions of personal belief, indeed, of faith – fundamentally no different from (though noticeably less tolerant than) much expression of the kind of faith Dawkins expressly wishes to eradicate. Of course, the fact that Dawkins’ and Atkins’ cited pronouncements are statements of faith does not of itself mean that those statements are false; but it does mean that they must not be treated as if they were authoritative science. What needs to be investigated is the category into which they fit, and, most important of all, whether or not they are true.

Before going any further, we ought, however, to balance the account a little by citing some eminent scientists who do believe in God. Sir John Houghton FRS writes: ‘Our science is God’s science. He holds the responsibility for the whole scientific story… The remarkable order, consistency, reliability and fascinating complexity found in the scientific description of the universe are reflections of the order, consistency, reliability and complexity of God’s activity.’15 Former Director of Kew Gardens, Sir Ghillean Prance FRS, gives equally clear expression to his faith: ‘For many years I have believed that God is the great designer behind all nature… All my studies in science since then have confirmed my faith. I regard the Bible as my principal source of authority.’16

Again, of course, the statements just listed are not statements of science either, but statements of personal belief. It should be noted, however, that they contain hints as to the evidence that might be adduced to support that belief. Sir Ghillean Prance explicitly says, for example, that it is science itself that confirms his faith. Thus we have the interesting situation in which, on the one hand, naturalist thinkers tell us that science has eliminated God, and, on the other hand, theists tell us that science confirms their faith in God. Both positions are held by highly competent scientists. What does this mean? Well, it certainly means that it is far too simplistic to assume that science and faith in God are inimical and it suggests that it could be worth exploring what exactly the relationships between science and atheism and between science and theism are. In particular, which, if any, of these two diametrically opposing worldviews of theism and atheism does science support?

We turn first to the history of science.

The forgotten roots of science

At the heart of all science lies the conviction that the universe is orderly. Without this deep conviction science would not be possible. So we are entitled to ask: Where does the conviction come from? Melvin Calvin, Nobel Prize-winner in biochemistry, seems in little doubt about its provenance: ‘As I try to discern the origin of that conviction, I seem to find it in a basic notion discovered 2,000 or 3,000 years ago, and enunciated first in the Western world by the ancient Hebrews: namely that the universe is governed by a single God, and is not the product of the whims of many gods, each governing his own province according to his own laws. This monotheistic view seems to be the historical foundation for modern science.’17

This is very striking in view of the fact that it is common in the literature first to trace the roots of contemporary science back to the Greeks of the sixth century BC and then to point out that, for science to proceed, the Greek worldview had to be emptied of its polytheistic content. We shall return to the latter point below. We simply wish to point out here that, although the Greeks certainly were in many ways the first to do science in anything like the way we understand it today, the implication of what Melvin Calvin is saying is that the actual view of the universe that was of greatest help to science, namely the Heb...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- 1. War of the worldviews

- 2. The scope and limits of science

- 3. Reduction, reduction, reduction…

- 4. Designer universe?

- 5. Designer biosphere?

- 6. The nature and scope of evolution

- 7. The origin of life

- 8. The genetic code and its origin

- 9. Matters of information

- 10. The monkey machine

- 11. The origin of information

- 12. Violating nature? The legacy of David Hume

- Epilogue

- References