This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

"I live with a price on my head...The kind of people that I spend my time engaging with are not usually very nice. On the whole nice people do not cause wars."

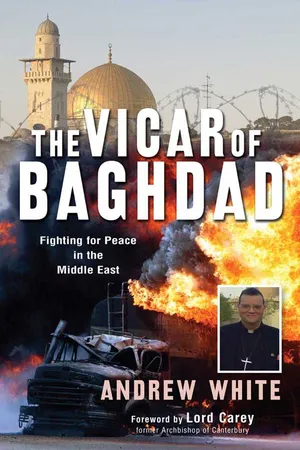

Andrew White is one of a tiny handful of people trusted by virtually every side in the complex Middle East. Political and military solutions are constantly put forward, and constantly fail. Andrew offers a different approach, speaking as a man of faith to men of faith. Compassionate and shrewd, gifted in human relationships, he has been deeply involved in the rebuilding of Iraq. His first-hand connections and profound insights make this a fascinating document.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Vicar of Baghdad by Canon Andrew White in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Biografie in ambito religioso. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Declaration of Intent

ONE DAY, I SHALL TELL the whole story of my involvement in the Holy Land (or, as I prefer to call it, the land of the Holy One). For the purposes of this book, I am going to recount two major developments in 2002 that I played a part in, both of which gave me invaluable experience that I was to use in Iraq in the years that followed.

For several years I had been going back and forth to Jerusalem, working hard with my colleagues on a number of grass-roots projects that brought Israelis and Palestinians together. We had also been trying to bring together Christians around the world. The Church – not least, the Church of England – is still very divided over the Holy Land. Sadly, most Christians either love Israel and the Jews and disregard, or even despise, the Palestinians (including Palestinian Christians) or they love Palestinian Christians and hate Israel and the Jews. Usually, they seek to justify their position from scripture. I found this very disturbing – at the very heart of Jesus’ teaching is the command to love your enemy, and yet so many of his followers today seemed readier to take sides than to seek reconciliation. I had endeavoured to bring unity to the Church on this issue – for example, taking groups of British church leaders to Israel and the West Bank on behalf of the Anglo-Israel Association – and had had some success as people saw the pain and the need of both sides in the struggle; but in general I had failed.

Then came the year 2000, the so-called year of jubilee. Many millions of pilgrims were expected in the Holy Land, and many millions of dollars had been poured into repairing the infrastructure of both Israel and the West Bank. The most famous pilgrim of all was to be John Paul II. Hundreds of thousands flocked to see him, and Israeli television actually covered his whole tour live. It was an amazing time, and the Pope with great diplomacy managed to keep everyone happy, even the politicians. The image that remains in my mind most clearly is of his visit to the Western Wall. The plaza was empty as he slowly approached the ancient stones, accompanied by one other person: Michael Melchior, a government minister who was an Orthodox Jew and (as it happened) the Chief Rabbi of Norway. I didn’t know it then, but Rabbi Melchior was soon to become one of my closest colleagues and friends.

Towards the end of that year, things started to go wrong politically. The fragile Oslo Accords were beginning to break down. President Bill Clinton had tried very hard at Camp David to forge an agreement on ‘final status’ negotiations between Yasser Arafat, the President of the Palestinian Authority, and Ehud Barak, the Prime Minister of Israel, but without success. The two sides told very different stories about what had actually happened. Subsequently, Israeli areas came under attack – in particular, rockets and mortar shells were fired into Gilo, a new town (some would see it as a settlement) on the outskirts of Jerusalem, from the adjacent Palestinian town of Beit Jala. Next, massive rioting erupted after Ariel Sharon (then leader of the opposition in the Knesset) visited the Temple Mount. Within days, what was to become known as the al-Aqsa Intifada had been declared. Violence was escalating rapidly, scores of people were dead and everything was falling apart. I would often cry to God with the words of the psalmist: ‘How long, O Lord? How long?’

Hope evaporated – and, to make matters worse, the conflict seemed to be becoming increasingly religious in character. The very fact that this new intifada, or ‘shaking off’, had been called ‘al-Aqsa’, after one of the world’s holiest Islamic shrines, seemed to suggest this. I continued travelling back and forth to Jerusalem, meeting with senior politicians, diplomats and religious leaders on both sides, searching for a way forward. Then, one day in 2001, over breakfast at the Mount Zion Hotel, everything changed. I was sitting with Gadi Golan, director of religious affairs in the Israeli Foreign Ministry, and he suggested that I should meet Rabbi Melchior, the man who had accompanied the Pope to the Western Wall. Now Deputy Foreign Minister, he was, Mr Golan said, a man who cared deeply about the role of religion in peacemaking. Like him, he had a vision to try to get all the religious leaders of the Holy Land to call for peace in this sacred place.

For the first time in a long while, I saw a chink of light. Maybe we could find peace again in the land of the Holy One. Maybe its religious leaders could play a positive role rather than a negative one. My meeting with Rabbi Melchior was very promising. We talked about the kinds of people we would need to involve and then discussed who should summon them all together. We decided it could not be either a Jew or a Muslim; it had to be a Christian. The Pope was too old and unwell for such an initiative, so we resolved that the person we had to approach was the Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, who had recently made a very successful visit to Israel and had also been to see Mr Arafat in Ramallah. Shimon Peres, then Israel’s Foreign Minister, concurred that he would be the right person, and I was to be the one to ask him.

Dr Carey is a kind and wise man with whom I get on very well, and he agreed to our proposal without any hesitation. That was the easy part. Now we had to find a suitable place where we could invite the religious leaders to come together. I decided that Egypt would be best, as a country where Jews, Christians and Muslims could safely meet in the Middle East. Next, we needed to speak to the key religious and political players there to get their support. I was assisted in Egypt by three exceptional people: Mounir Hanna, then Bishop of Egypt in the Episcopal Church in the Middle East; Dr Ali El Samman, a former diplomat who was now an adviser to the Grand Imam of al-Azhar, Sheikh Muhammad Sayed Tantawi; and the British ambassador to Egypt at the time, John Sawers. They devoted many hours to this endeavour and could not have been more helpful. Finally, we chose Alexandria as the venue, and specifically the exclusive Montazah Palace Hotel, which had its own extensive and very secure private grounds on the sea front. I made several visits to the city to make preparations and had many meetings with senior religious figures, from the Grand Imam to the head of the Coptic Church, Pope Shenouda III.

In Israel, the negotiations were intensive. We agreed that, if we wanted to be sure that this summit would be regarded as a success, it would have to issue a serious declaration. I wrote the first draft of this myself with my assistant, Tom Kay-Shuttleworth, and we would discuss it into the small hours with the various delegates on the planning committee we had formed. It took several weeks of this before they finally approved it. It was now nearly Christmas and I had to return home to Coventry for a week. The gathering had been scheduled for March 2002, but on Christmas Day Rabbi Melchior phoned me to say that it could not wait that long: the violence was escalating so sharply, and so little progress was being made on the peace process, that the declaration was needed as soon as possible. I told him he needed to speak to Dr Carey, which he did immediately. The following day, I travelled 160-odd miles down to Canterbury to see the Archbishop. He had listened to Rabbi Melchior and, after asking my advice, decided to bring the summit forward to January.

Some of his staff were not exactly pleased by this – it meant major changes to his diary, including the cancellation of a trip overseas. Within a few days, I was back in Jerusalem, trying to finalize details. It was a mammoth task. There was also the issue of money – the summit was not going to be cheap and we needed the funding quickly. To find $200,000 in a few days was not easy, and I don’t think I have ever prayed so hard for money. I approached a friend of mine, Lady Susie Sainsbury, a committed Christian who chairs the Anglo-Israel Association, and she came up with more than half of what we needed from one of her trusts. Other funds came from the Church of Norway and the World Conference of Religions for Peace, which were both to send observers.

I did further work on the ground in Jerusalem and the West Bank, spending hours with Yasser Arafat, representatives of the Israeli government and various religious leaders. While the Israeli team was led by Rabbi Melchior, the Palestinian Muslims were led by the equally inspirational Sheikh Talal Sidr, who was a minister in the Palestinian Authority. The Christians were to be led in Alexandria by the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Michel Sabbah. Tom and I would talk with them into the night at the Mount Zion Hotel as we worked on the final draft of the declaration. We also shuttled back and forth to Cairo, where we spent hours with Dr El Samman going through the document word by word to ensure that it was acceptable to the Grand Imam of al-Azhar, who as the highest authority in Sunni Islam was to be co-chair with Dr Carey of the gathering in Alexandria. In addition, we had regular sessions with the British ambassador, John Sawers, the Israeli ambassador and representatives of the Egyptian government. All of these meetings were very positive. So far, so good.

Then, on 19 January 2002, I returned to London to brief Dr Carey before our scheduled departure for the Holy Land the next day. Things there were now very difficult. Furthermore, the Israelis had decided that no foreigners were allowed to see Mr Arafat (though by now I had realized that such bans usually didn’t apply to me). On my way into Lambeth Palace, I met a senior member of the Archbishop’s staff who politely informed me that we would not be going if he had anything to do with it. He didn’t believe we would get access to either Mr Sharon (who was now Prime Minister) or Mr Arafat, let alone secure their support, and he thought I was just wasting Dr Carey’s time. The two of us went in to see the Archbishop, and this man gave him his advice. Calmly and quietly, Dr Carey said that nonetheless we were going.

Early next day, Tom and I made our way to the VIP lounge at Heathrow to meet Dr Carey. His wife, Eileen, was accompanying him – like him, a quite exceptional person – as well as two of his staff. With me, unusually, at Dr Carey’s insistence, was my wife, Caroline. I briefed the Archbishop during the flight and in due course we landed in Tel Aviv, where we were met by Britain’s ambassador to Israel, Sherard Cowper-Coles. He had been very helpful to us and now he gave us a warm welcome. In Jerusalem, we were met by the consul-general, Geoffrey Adams, who was responsible for Britain’s relations with the Palestinians. He, too, had been very supportive.

After dinner with him and his wife, we were driven in armour-plated cars to see Yasser Arafat in his compound, the Muqata, less than ten miles away in Ramallah. We arrived there surrounded by Palestinian security vehicles with sirens screeching; but, despite the tension outside, it was a very pleasant meeting. Mr Arafat could not have been more positive. He told Dr Carey how important the gathering in Alexandria would be, as religious leaders from Israel and Palestine came together for the first time to search for peace. Also present at this meeting in Ramallah were Ahmed Qurei (also known as Abu Ala) and Mahmoud Abbas (or Abu Mazen), who were both to serve as prime minister of the Palestinian Authority the following year, and Mr Arafat’s chief negotiator, Saeb Erakat. (Early on, I had had some heated arguments with Mr Erakat, but later he was to become a good friend.) We returned to Jerusalem feeling encouraged, to wait to hear whether we would be able to see Ariel Sharon.

As the sun rose the next day, things were looking hopeful. It seemed we would be able to meet Mr Sharon that very morning, before a Cabinet meeting. Accompanied by Mr Cowper-Coles, Dr Carey and I made our way to the rather spartan prime ministerial office, where we were joined by Rabbi Melchior and his immediate boss, Shimon Peres, who, always very supportive, now endorsed without reservation the declaration we had drafted. Mr Sharon was a different matter. On his desk, he had a copy of the Hebrew Bible (as he did for all meetings with religious leaders) and he reminded the Archbishop of the words of Pope John Paul II: that to Christians this was the Holy Land, but to Jews it was the Promised Land. The message we got was: ‘Don’t mess with our land!’ Nonetheless, it was remarkable that both Mr Sharon and Mr Arafat, two people who would not talk to each other, approved our draft declaration. It was this agreement that we wanted to seal and share with the world.

It was at Ben Gurion Airport, where we were due to catch a specially chartered plane to Alexandria, that the problems really started. There were some 45 people in our party in total, including the Archbishop (who had insisted on travelling with us rather than flying VIP, to show solidarity with the Palestinian dignitaries – who of course had no privileges at all). We had given everyone’s name to the Israeli security services beforehand, and were also being accompanied on the flight by some agents from Mossad. However, while the Jews and Christians got through all the checks without difficulty, it was a very different matter for some of the Muslim delegates. The computers at passport control almost blew up! They could not allow these individuals onto an aircraft at Tel Aviv. For well over an hour we tried every argument and appeal we could think of to get them through. By now the whole party, archbishops, rabbis and all, was insisting that if our Muslim colleagues could not board the plane, none of us would.

At long last, we were all allowed through. Mr Cowper-Coles, who was still with us, had rung Danny Ayalon, Mr Sharon’s senior foreign-policy adviser, and some key people in Israeli intelligence, and this had done the trick. We were finally on our way to Alexandria. The plane landed very late, and then, surrounded by Egyptian police, we were driven to the Montazah Palace complex. My staff from Coventry Cathedral were already there and fortunately had removed from the bedrooms every painting that featured a naked woman, so that no offence would be caused to such senior religious leaders.

The summit began without further delay, at about 3pm. As Dr Carey opened the proceedings with a moment of silence, there was an air of great expectation in the room. We all knew we were on the verge of making history. The official language of the meeting was English, but there were interpreters on hand, provided by the Egyptian government, to translate to and from Hebrew and Arabic. The Israeli government had had the declaration we had written printed out on beautiful parchment paper, and I imagined that the signing was a mere formality before we got down to discussing our real business: how to put it into practice. To my horror, however, it became apparent that some of the Palestinian delegates would not sign it as it stood. The Christians had not really been involved in the weeks of preparation, and Patriarch Sabbah and the Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem and the Middle East, Riah Abu el-Assal, in particular believed that the declaration did not adequately reflect their concerns. In my experience, Christians in Palestine often seem to feel they have to be even more Palestinian than the Muslims, to show how committed they are to the cause.1 To be honest, this (as well as the rivalries and tensions between the different denominations) can make them very difficult.

Had all our work been in vain? When George Carey wrote his autobiography, Know the Truth, after his retirement as Archbishop of Canterbury, he said that this meeting was the hardest he had ever chaired. I don’t doubt it. The delegates separated to work through the issues, with Bishop Riah and Archbishop Boutrous Mu’alem sitting with the six Israeli delegates, as they were entitled to, in the hope that they could influence them. The sticking points were not theological but political, the principal issues being whether the statement should mention the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and whether as it stood it implied that Palestinians were largely responsible for the bloodshed. The Palestinians made it clear that they thought the Israelis were primarily to blame. If the declaration was to condemn violence, they insisted, it must condemn the violence that had been committed against their people. The issue of the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their land in what is now Israel also came into the dispute.

Much of the discussion was conducted in separate groups, but periodically we all came together and then there was a great deal of shouting on both sides. It was obvious that all the delegates alike felt strongly that they must not undermine their own politicians or betray the interests of their people. At first, no one was willing to move an inch – and in any negotiation when this happens it generates anger and frustration. I had to keep my opinions and emotions to myself – my role was to go back and forth between one group and the other to try to find a form of words acceptable to both. In the end, it was the Israeli rabbis who proved to be more prepared to give ground, though not on major issues such as the status of Jerusalem.2 The only man on the Palestinian side who was ready to make compromises was a Muslim, Sheikh Talal. He had himself moved a considerable distance in his own life, from being one of the founders of Hamas to serving as a minister in Yasser Arafat’s administration.

Typically, only the most senior Muslim delegates – Sheikh Talal and the chief justice of the Palestinian shari’a courts, Sheikh Taysir al-Tamimi – actually took part in the debate at all. The other two, the muftis of Bethlehem and of the Palestinian armed forces, did not say a word. (In fact, after the summit was over, the latter went to live in Britain and, to my knowledge, never returned to the West Bank.) As for me, when I wasn’t needed by the various delegates I sat with Dr Carey and the Grand Imam, who were not involved in the minutiae of the discussions. The latter had a long conversation with the Sephardi Chief Rabbi, Eliyahu Bakshi-Doron, which in itself was quite historic.

At midnight, Dr Carey retired to bed, after instructing me that the problems must all be sorted out by the morning. Into the small hours the delegates argued in their separate groups, battling to find a resolution. I moved constantly between the Palestinians and the Israelis, but found them both so fixed in their positions that I began to despair. How could we move forward in the face of such intransigence? At 5am, I went to bed myself. It had certainly been the most difficult meeting I had yet taken part in, and I was almost in tears as I went back to my room. I woke my wife and we prayed, but it all seemed hopeless. Night after night we had worked. We had all seemed to be moving in the same direction, we had gone so far and got so close, yet it looked as if now we were going to lose everything. Probably for the first time ever, I asked myself the question: Why were we failing? My past experience of conflict resolution had taught me that people can change their minds very suddenly – but in the Middle East, it seemed, Western techniques simply did not work. I lay awake thinking about my calling to be a minister of the gospel. Was this really what it was about? I longed to be back in my old parish in London, where the people loved me and I loved them; but I knew deep down that that was no longer my calling. My true vocation was what I was doing now.

Three hours later, I got up to go and tell Dr Carey that we had not succeeded. When I spoke to Tom, however, he actually encouraged me. ‘We mustn’t give up,’ he said. He had been with me from the beginning of this process, an outstanding assistant, and he had deep faith. He, too, knew that God had called us to this and he was not going to quit. That morning, we were joined once again by John Sawers. He is a wise man and he, too, was not going to let this historic endeavour founder.

After breakfast, the Archbishop of Canter...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT

- DEDICATION

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION: A Quite Unexpected Theatre

- CHAPTER 1: Declaration of Intent

- CHAPTER 2: A Painful Delivery

- CHAPTER 3: From Darkness to Darkness

- CHAPTER 4: A Measure of Progress

- CHAPTER 5: Knowing the Right People

- CHAPTER 6: Giving Peace a Chance

- CHAPTER 7: The Most Wonderful Church in the World

- CHAPTER 8: The Kingdom, the Power and the Glory

- WHO’S WHO

- PHOTO SECTION