![]()

Chapter 1

PRIVATE RYAN’S DEFIANCE

– Perham Down, October 1916 –

Every man I have spoken to is absolutely sick of the whole business.2

— Private Edward James Ryan to Ramsay MacDonald MP, 18 October 1916

In October 1916, a young Australian soldier from the 51st Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was recovering in England from wounds and shell shock.3 He was Private Edward James Ryan, Service Number 4635, originally from Broken Hill. In June that year, he had suffered burns and abrasions to his face when an artillery shell exploded very close to his trench. He was fighting near Fleurbaix, just south of Armentières, in France. He spent some weeks in hospitals on the French coast. After returning to the front, he was injured again in August, his left hand crushed. This second time he was transferred to hospitals in England. On top of his physical wounds, the doctors assessed him as a shell-shock case. He spent weeks convalescing. Finally, at the end of September 1916, he was ordered to return to service with the AIF in England, at a large army camp known as the ‘No. 1 Australian Command Depot’. It was located in open country at Perham Down, close to the Wiltshire-Hampshire border, and near the edge of the British Army’s desolate training grounds of Salisbury Plain.

Private Ted Ryan was housed at No. 3 Camp inside the military complex at Perham Down. The Australian soldiers usually called it by the plural form, ‘Perham Downs’. Perhaps this was more in line with the Australians’ expectations of what a little piece of rural England should be called, with the word ‘Downs’ suggesting the soft, green, pastureland of their imaginations – a restorative place, that might soothe those wounded in body and soul. In fact, no solace was to be found there. The area was a sombre network of parade grounds fringed by ‘long greyish coloured huts’, all cheaply built, and often very chilly.4 More than five thousand soldiers could be crammed into this facility at any one time, with thirty men per wooden hut. There was also a smattering of tents for any overflow of soldiers, and for those temporarily shifted out of the huts during their periodic disinfections to kill lice and fleas.

The camp, formerly a British facility, had been allocated to the Australians in mid-1916. It was set up in the expectation that soldiers wounded in the first battles to be fought by the Australian divisions in France, during the coming summer offensive, would be sent here to recover and retrain. Thousands came. Many were survivors from the horrific battles around the River Somme, Fromelles, Pozières, and Mouquet Farm, or ‘Mucky Farm’ in the troops’ dialect. After a stint in hospitals scattered across Britain, those soldiers who could be restored to some degree of strength were despatched to Perham Down.

The camp was officially designated a ‘Hardening and Drafting Depot’. The Australians’ commanders sent the men here to be toughened up in preparation for their return to the front. After assessment, some would be funnelled to other Australian depots in England for still more training. Others, once ‘hardened’, would be ‘drafted’ directly from Perham Down back to their units in France.

Surrounding the camp were firing ranges for rifles, machine guns and mortars. The ranges were backed up against several small hills near the camp, with banks of earth added, providing safe backstops. There was also an extensive network of practice trenches in fields about two kilometres away, near the tiny village of Shipton Bellinger. These trenches had been initially dug into the chalk by British units in 1915, for the training of the volunteers in Kitchener’s New Army who would eventually fight at The Somme in July 1916. The Australians had inherited these practice trenches. They included front-line trenches with fire-steps, support and communication trenches, dugouts, shelters, latrines, aid posts, machine-gun emplacements, and even ‘German’ trenches, known as ‘Bedlam trenches’. The trenches came complete with screw-pickets laced with barbed wire. Thus, a replica of a part of the Western Front was created on Salisbury Plain, where troops could rehearse storming German trenches. All these diggings honeycombed more than a hundred hectares of the countryside around Perham Down, scarring the landscape.5 Here in the autumn of 1916 Australia’s wounded and damaged from the Somme battle fronts were schooled again in trench warfare. No doubt, with outbreaks of rifle and machine-gun fire, and with Mills bombs erupting regularly, many men were violently flung back in their minds, by the sounds and sights and smells of mechanised warfare, to the haunting scenes of devastation that they had witnessed in France.

During the English autumn of 1916, Perham Down was a bleak camp, earning its colloquial nickname among the troops as ‘Perishing Downs’.6 ‘The rottenest hole on earth’, was one soldier’s blunt description after arriving there in October 1916, the same month as Ted Ryan. ‘No mattresses to sleep on. Bare boards.’7

The statistics generated at the camp make grim reading. At the end of October 1916, the No. 1 Command Depot’s war diary recorded that 5,311 men were ‘on strength’ at the camp. Some 3,266 men had arrived during the month, and altogether 8,577 men had been ‘handled’, with many sent on to other camps. Only 79 soldiers at Perham Down had been deemed fit to return directly to France that month.

Sagging discipline at Perham Down began to worry the officers. The depot’s war diary for October 1916 tried to look on the bright side, asserting that discipline was generally ‘good’, given the large numbers of men and ‘the many indifferent characters’ moving through the camp. But this was wishful thinking. Figures showed that there were in fact 440 cases of ‘absence without leave’, 45 remands for a District Court Martial, and a total of 766 incidents requiring punishment during the month of October. The lure of London, and even nearby Stonehenge, was too much for many soldiers. Perhaps most distressingly, the war diary also recorded some cases of men ‘taking fits’. It offered a matter-of-fact explanation: the nervous fits endured by many men during training ‘appear to be due to the nearness of the depot to the Trench Mortar Range. The noise, when practice is going on, affects the Shell Shock cases sent here for short convalescence.’8 And there was a lot of noise.

A Letter from the Killing Floor

After almost three weeks at Perham Down, Private Ted Ryan, one of those unfortunate victims of shell shock, resolved upon a risky course of action: he would denounce the war. Something irresistible arose in his blood: he felt he must record his own protest against the chaotic mass killing that he had seen in France, the mass killing that politicians in Britain, and in Australia, were apparently quite willing to see prolonged. He resolved to tell the truth about the horrors he had seen.

On 18 October 1916, Ted Ryan found a quiet place in the camp to sit down and compose an angry letter condemning the war and roasting those behind it. Soldiers wanting to write often found the huts at Perham Down too noisy, but it was possible, as one put it, to ‘sneak away into a quiet corner of the YMCA [Young Men’s Christian Association] to write romantic letters to the folks at home’.9 The YMCA, or ‘the Y’, was just one of a number of church-run organisations in the camp. It provided free writing paper.10

Ted Ryan planned to send a very unromantic letter. He addressed it to the man the pro-war newspapers depicted as the best-hated and most dangerous man in Britain, the anti-war Labour politician Ramsay MacDonald MP. The notorious Scot was a veteran socialist and former chairman of the British Labour Party at Westminster. In August 1914 he had resigned from that party leadership position in protest against Britain’s decision to rush into war or, more accurately, against his own party’s failure even to register its dissent by abstaining on the parliamentary vote to fund the war from a ‘War Credit’. Immediately engulfed in controversy, MacDonald nevertheless held firm to his dissenting position, while being monstered in the press as no better than an ‘agent of Germany’, a ‘pro-German’, a ‘traitor’.11

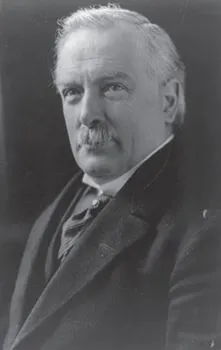

Ramsay MacDonald

Ryan’s letter to MacDonald glowed with the white heat of passion. Importantly, he claimed to speak for most Australian soldiers. And he had big truths to tell. The surviving Australian soldiers from the bloodshed in France, Ryan insisted, hated the war. They called the battlefield ‘The Abattoirs’. Indeed, under shellfire every trench was potentially a kill-box. He seized his chance to put down on paper the real opinions of those Australian troops, because the British press was hyperventilating about how much the brave Australians ‘relish the glories of war’. For instance, Ryan wrote, two men fresh from the battlefront had just told him that they ‘would rather be shot than face another bombardment like we received at Pozières’. So, Ryan complained, the blood-and-thunder newspapers were lying about the Australians! Ryan railed at one newspaper in particular for depicting the Anzacs as ‘bright & cheering, hooraying’ as they came away from the Somme battlefield. The truth was, wrote Ryan, that the ‘frightfulness’ of the bombardments at the front was ‘beyond their imagination’. Every soldier he had talked to was ‘absolutely sick of the whole business’.

Ryan clearly knew not only of MacDonald but also the leading pro-war politicians. He heaped praise upon MacDonald for his consistent anti-war stand – for refusing, as Ryan put it, to hide behind ‘the veil of Patriotism’ like so many stay-at-homes, safely spouting their determination to fight on to the ‘bitter end’ while too old for military service. In this spirit, Ryan turned his fury on Herbert Henry Asquith, the British Prime Minister, and David Lloyd George, his Minister of War. These two were contemptible and cruel, Ryan argued, for vowing to fight on, at any cost, until military victory was achieved. Did Lloyd George, in his ‘nice spring bed’, even think of those in the trenches with their ‘nerves shattered to the uttermost’? Why did both Asquith and Lloyd George say ‘we are out to crush Germany’? Waging war until Britain could impose her peace terms upon Germany would ‘make thousands face this hell’.

David Lloyd George

Ryan’s letter also showed he was in touch with the latest sensations in British politics. Only a month before, in late September 1916, Lloyd George had slapped down the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson. America was still neutral at this stage of the war, and Wilson had repeatedly urged negotiations. Lloyd George chose to block him. In a newspaper interview given to an American journalist, to be published across the world, Lloyd George stubbornly insisted that Britain could not discuss peace terms and must refuse Wilson’s offers – or any offers – to mediate. This enraged Ryan. He piled on the rhetorical questions. By what right, he asked, did Lloyd George shout ‘Hands off Neutrals’? ‘Now, Mr MacDonald, why shouldn’t we know what terms of Peace we are fighting for, why shouldn’t we discuss what terms we are supposed to accept?’ For Ryan, Britain’s lust for imperial conquest was the real stumbling block. Britain was committed to ‘her old ideal’ – to ‘Conquer’. Britain had no real commitment to the ‘supposed new ideal’, the ideal of ‘Peace’. The ‘horrors of war’ in France were mind-numbing. What could Britain possibly gain that would be worth ‘such a human sacrifice?’

Fear and loathing at ‘Perishing Downs’

What had prompted this outburst from Australia’s Private Ryan? Political controversies erupting across the mess tables at Perham Down had a lot to do with it. A referendum on military conscription was due to be held in Australia at the end of October 1916. Australian troops deployed overseas were given the chance to vote early. This was to ensure that the soldiers’ votes could be counted in the final tallies. Noticeboards at Perham Down explained to the troops that they would cast their ballots on 19 October – the day after Ryan penned his angry letter to Ramsay MacDonald.

Those supporting conscription in Australia had high hopes that the Anzac troops would lead the way, and give a resounding ‘Yes’ in favour. General Sir William Birdwood, the British Commander of the AIF, and Labor Prime Minister William ‘Billy’ Morris Hughes, had blitzed Perham Down with ‘patriotic circulars’ pleading the ‘Yes’ case. Birdwood argued that ‘no sacrifice...