- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

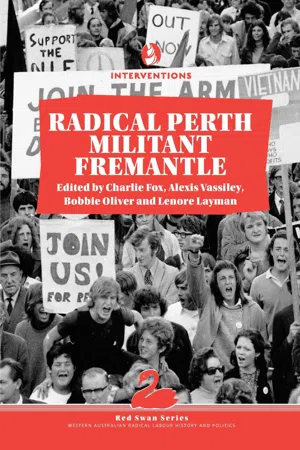

Radical Perth, Militant Fremantle

About This Book

Radical Perth, Militant Fremantle tells 34 fascinating stories of radical moments In the cities’ past, from as long ago as the 1890s and as recent as Occupy: the revolutionary theatre of the Workers Art Guild; the riot of unemployed workers outside the Treasury building; rock concerts inside St Georges Cathedral; bodgies and widgies cutting up the dance floor at the Scarborough Beach Snake Pit; the Point Peron women’s peace camp, and many more.

This revised 2 nd edition bring four new tales: student radicalism at Curtin University (then WAIT), Perth’s very-own Green Bans; Perth solidarity with the famous strike of Aboriginal pastoral workers; and the unknown tale of striking Chinese seamen on the Fremantle waterfront, who faced brutal repression, but won support from Fremantle unionists.

This engaging, inspiring book charts Perth and Fremantle’s radical past, uncovering the obscure and neglected, reframing the better known, opening new windows on Perth and Fremantle’s history. It is structured as three self-guided walking and driving tours, so readers can visit the very places and buildings where these hidden histories took place.

Frequently asked questions

Information

RADICAL

PERTH

WALKING RADICAL PERTH

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction by Charlie Fox

- Part 1: Walking Radical Perth

- Part 2: Walking Militant Fremantle

- Part 3: Driving the Radical Suburbs

- Select Bibliography

- Picture Credits

- Editors and Contributors