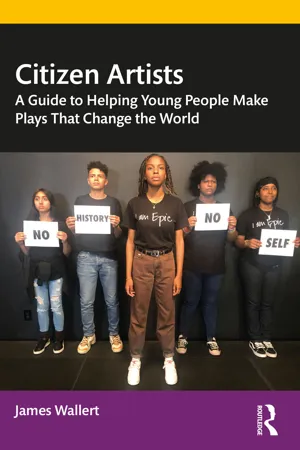

Citizen Artists

A Guide to Helping Young People Make Plays That Change the World

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

Citizen Artists takes the reader on a journey through the process of producing, funding, researching, creating, rehearsing, directing, performing, and touring student-driven plays about social justice.

The process at the heart of this book was developed from 2015–2021 at New York City's award-winning Epic Theatre Ensemble with and for their youth ensemble: Epic NEXT. Author and Epic Co-Founder James Wallert shares his company's unique, internationally recognized methodology for training young arts leaders in playwriting, inquiry-based research, verbatim theatre, devising, applied theatre, and performance. Readers will find four original plays, seven complete timed-to-the-minute lesson plans, 36 theatre arts exercises, and pages of practical advice from more than two dozen professional teaching artists to use for their own theatre making, arts instruction, or youth organizing.

Citizen Artists is a one-of-a-kind resource for students interested in learning about theatre and social justice; educators interested in fostering learning environments that are more rigorous, democratic, and culturally-responsive; and artists interested in creating work for new audiences that is more inclusive, courageous, and anti-racist.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Part IThe Citizen Artist methodology

1How do we transform art into activism?

JEREMIAH: School segregation, That systematic placement, Race and class, don't make me laugh. That shit goes deeper than thin cloudy glass. Right past society's foundation, Back to America in the making. The original sin: Race. The original sin: Race. The original sin: Race.

OLIVIA: Just a social figment, it controls this place. Causing fear of my pigment, scared to look in my face. Looking down at me like I'm a disgrace.DAVION: Knowing that nobody wants to admit it But this country's ruled by fear. Move your hands, stop covering your ears. Open your eyes.NAKKIA: See that shit is so embedded that if you don't rise, Six feet under is where you're headed-buried alive.NASHALI: By the lies, false hopes, false causes, false endorsements: crazy ride. This is a rollercoaster and yeah you on it. So tell your mama not to take off her bonnet.JEREMIAH: Just sit, relax, and enjoy the show cause we own it. Laundry City.

MR. MADISON: Soon we will be admitting new students to our school.KEEPING IT 100: The white students are a-comin'.MR. MADISON: Nothing will change.KEEPING IT 100: Everything's changing.MR. MADISON: This is happening because of the rezoning going on in Brooklyn.KEEPING IT 100: This is happening because white people are colonizing Brooklyn.MR. MADISON: This is a great opportunity to make our school great again!KEEPING IT 100: This is a great opportunity to snatch that white money!

MRS. MALAVÉ (English translation):What does this mean? White people moving in? Here? Of all the places? We're quiet. We don't even get news coverage whenever a little boy is shot out here. What will they bring? Higher rent. More and more white people. I'm gonna get kicked out. I can't. This is the only place I know. I grew up here- been here my whole life. Mami and Papi are gone, God rest their souls, so I can't even ask them for advice. What am I gonna do? How will this affect Jeylin? Her school? Maybe the government will finally help them. Is that who takes care of the schools?

POORELL: Yo, my mans!RICH: OK, you see this line? That's my side. This is your side. Got it?POORELL: What the hell are you doing?RICH: Rezoning.POORELL: What?RICH: This side is safe. That side is dangerous.POORELL: Are you serious? You selfish prick! (POORELL pushes RICH)RICH: See! That's what I'm talking about! Your side is too dangerous! I don't feel safe.

MR. WELLS: What is your definition of integration?PHILLIP: I'm not really sure what we mean by integration. What I've seen when we talk about integration, it is about Black and Latino kids going to white schools to become better. That isn't integration, that's- in my view-assimilation.AMY: I consider integration when you do the hard work of valuing what each person brings to that setting. Integration is where we learn to understand each other and appreciate each other and nobody's story or history is more important than another's.JOE: I think where we get confused is conflating the quest for adequate educational opportunities with a quest for integration. The theory of action was if you import basically white middle class students, they would then advocate for all of the students in the school. They had more social and political capital and they would essentially serve as the saviors for the Black and Latino students in the school. I think that's racist. I think it's classist. I don't believe in the savior complex- that you need to have folks swoop in and save the poor Black and Latino children. I believe that Black and Latino folks have agency and power that have been untapped.SARAH: For me, it's not that certain communities are less powerful; it's that certain communities haven't been given the floor. How do we give people the floor? Segregation was intentional. Integration has to be intentional. Segregation was forced. Integration has to be forced.PHILLIP: Who says the goal is integration? I think for me the goal is about having high quality schools.TANYA: If integration made money somehow, then America would do it.SARAH: I think the worst part about segregation is that people end up feeling like there's something wrong with them. The worst part of segregation is young people feeling like they're stupid, they're bad, they're troublemakers, they're not worth it. That's the worst part.

DAVION: Is separate but equal fair?ENTIRE ENSEMBLE: Is separate but equal fair?

OLIVIA: At Epic, we like to have a conversation after every performance and we always ask our audience the same first question: Imagine that two weeks from now, one morning you wake up and find yourself thinking about Laundry City. What is it that will be going through your mind: a line, a character, an idea, a question? What do you think will resonate with you over time?

JEREMIAH: Jim!JIM: What's up?JEREMIAH: I'm feeling emotional about all this.JIM: Oh yeah?JEREMIAH: Yeah, I feel like an activist.JIM: You are an activist.JEREMIAH: No, I mean, I feel like I'm in a room full of people who can actually change things and they're listening to me.JIM: Yeah.JEREMIAH: That's intense!JIM: Yeah!JEREMIAH: O.K. I'm going back in.

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Introduction

- Part I The Citizen Artist methodology

- Part II The Citizen Artist curriculum

- Part III The Citizen Artist plays

- Conclusion

- Index