![]()

PART I

North African Corps Commander

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

First Day of Battle

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE S. Patton Jr. unholstered his ivory-handled Smith and Wesson .357 Magnum revolver, aimed, and fired. The bullet whizzed past the head of his intended target. He missed, but he achieved his goal just the same. His target, a local Moroccan man picking up an American rifle on Fedala beach, got the message, dropping the rifle and darting off. American soldiers nearby popped their heads above their sandy foxholes to investigate what had disturbed the relative quiet. Patton had announced his presence on the battlefield his way, with his first shot fired in World War II.1

Sunday, November 8, 1942, was a long day for Patton. It started at 2:00 a.m. when he awoke, fully clothed in khaki trousers, shirt, and tie, in the captain’s cabin aboard the USS Augusta, the flagship of the American Western Task Force. After only five hours of sleep, he got out of bed and put on a pair of regular Army buckle boots instead of his flashier cavalry ones. He tucked his pants into his boots and pulled on a simple button-up infantryman’s jacket with the triangular I Armored Corps patch on the breast, identifying his command prior to taking on the mantle of the Western Task Force. He hung a pair of binoculars around his neck, a camera case over one shoulder, and donned his war helmet. He chose not to strap on his two ivory-handled pistols, instead having them packed on a landing craft that would take him to shore. The double-starred rank of a major general gleamed from his helmet, his collar, and shoulders. There would be no mistaking him on the battlefield.2

The face that greeted Patton in the mirror reflected almost fifty-seven years of adventurous living. His silver-white hair had receded to his temples, but a few strands still graced his crown. Crow’s feet spread from the corners of his eyes, and skin hung slightly from his jowls on either side of thin lips. His teeth were stained brown from a lifetime of smoking cigarettes, cigars, and pipes. Despite an outdoor life of horseback riding, sailing, and soldiering, a small paunch had developed in his midsection. He explained his weight gain in 1945 thus: “My weight is due to more brains.” Scars from horse-riding accidents, competitive sports, and bullets speckled his body, but his uniform provided ample cover.3 Dressed for battle and fully awake, he went on deck to see the lights of the Moroccan city of Fedala. The sea, predicted to be pitching and turbulent, lay perfectly still, a dead calm. “God is with us,” he thought.4

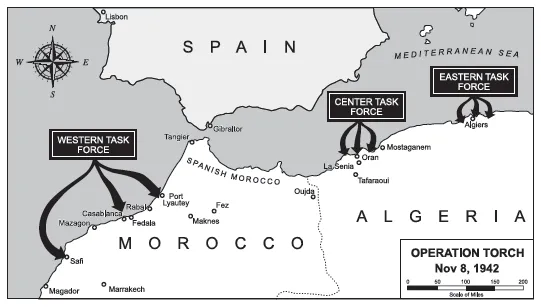

Patton stood at the tip of the spear of thirty-five thousand men ready to storm three Moroccan beaches. His Western Task Force comprised 106 large naval vessels and numerous small landing craft. He commanded soldiers from the 3rd Infantry Division and elements of the 9th Infantry Division. He had 252 tanks from both the 70th Tank Battalion and the 2nd Armored Division. His air force claimed 229 Navy and Army aircraft. Naval guns would handle any sustained heavy fire beyond his soldiers’ reach. The task force was split into three groups: the Northern Attack Group, consisting of the 9th Infantry Division’s 60th Combat Team under Brigadier General Lucian Truscott attacking Mehdia and Port Lyautey; the Center Attack Group, consisting of the 3rd Infantry Division, under Major General Jonathan W. Anderson, taking Fedala, sixteen miles north of Casablanca; and the Southern Attack Group, consisting of the 2nd Armored Division and the 9th Infantry’s 47th Combat Team under Major General Earnest (Ernie) Harmon, attacking the port of Safi, 150 miles south of Casablanca. Patton would go ashore with Anderson’s troops.5

Patton’s attack was just one part of Operation TORCH, which brought western Allied forces onto North African shores in three separate amphibious assaults. Two task forces of combined American and British troops departed from England to simultaneously attack the cities of Algiers and Oran, both in Algeria. Only Patton’s all-American Western Task Force journeyed across the Atlantic Ocean for Morocco’s shores. TORCH was the United States’ first offensive in the war against the Axis powers and came almost a year after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. However, the Allies would not be fighting the Germans or Italians during TORCH. Instead, they faced the Vichy French.

As Patton waited to begin his first attack of the war, Europe had been ablaze for the last four years. Adolf Hitler’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, signaled the official opening of World War II. The Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin soon joined him in dividing up Poland. Stalin next invaded Finland while Hitler attacked Norway, ejecting British and French forces. Then, on May 10, 1940, Hitler attacked France and the bordering Low Countries, driving the Allies west. British prime minister Winston Churchill saved a portion of his army from the beaches of Dunkirk, but Great Britain stood alone until the next year, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. While war raged in Eastern Europe, the western Allies fought the Germans in the seas and skies and faraway battlefields. German forces invaded Yugoslavia and Greece. They also dropped paratroopers onto Crete. In North Africa fighting seesawed across the Egyptian and Libyan deserts after the British defeated an attacking Italian force. To contain the British gains, the Germans sent a corps commanded by General Erwin Rommel to help their whipped partner.6

Map 1. Operation TORCH, November 8, 1942

Rommel soon went on the offensive and drove the British back to Egypt. Attacks and counterattacks raged across the desert, with Rommel constantly fooling or overwhelming the British. A worried Churchill continued to replace his desert commanders until he landed on General Bernard Law Montgomery, who restored morale and, after an intense battle at El Alamein, overwhelmed and drove Rommel west in early November 1942. Operation TORCH was meant to help Montgomery by getting men and arms behind Rommel, shutting off his retreat to Tunisia, surrounding him, and eventually destroying his army. This was the world that Patton entered the morning of November 8.

Patton’s mission was almost the operation that wasn’t. During the TORCH planning sessions in Washington, D.C., in which Patton took part, the British protested that his assault on Morocco was unnecessary. They argued that the port at Casablanca was too distant—thirteen hundred miles—from the Tunisian battlefield where the British hoped to fight the Axis. They also contended that the Atlas Mountains made travel between the two locations difficult. But the Americans wanted possession of Africa’s closest port to the United States and argued vehemently for the operation. After one particularly heated debate, an infuriated Patton stormed home, picked up a foot-tall Hawai’ian war statue, marched out to the backyard, and threw it into the pond. The statue, nicknamed “Charlie,” had been a good-luck gift from Patton’s wife. But with the Moroccan landings stymied by politics, Patton felt the war gods had turned on him and took his wrath out on Charlie. Still, the British eventually bent to the Americans’ desire to attack Morocco and Patton’s Western Task Force set sail for North Africa.7

Patton spent the fifteen-day voyage to Morocco exercising, attending religious services, and shooting an M1 carbine rifle off the ship’s fantail. He exercised by walking around the ship, using a rowing machine, or holding onto his dresser and running in place; by his calculations, 480 steps equaled a quarter mile. He took pictures of his staff and enjoyed the Augusta’s amenities: a private bathtub in his room and well-prepared meals: “I have to watch eating too much,” he confessed. Everywhere he went on the ship a Marine guard shadowed him, to Patton’s irritation. He filled his daily lulls by writing letters and diary entries and reading books, including the Koran. Emotionally, he oscillated between worrying about the coming battle and trusting in fate.8

As the task force neared the North African shore, Patton’s war speech played over each ship’s public address system. “Soldiers and sailors,” his voice barked, “We are to be congratulated because we have been chosen as the units of the United States Army best trained to take part in this great American effort.” In a booming, though high-pitched tone, Patton explained the operation’s objectives, described the enemy, and offered encouragement: “When the great day of battle comes, remember your training, and remember above all that speed and vigor of attack are the sure roads to success, and you must succeed—for to retreat is as cowardly as it is fatal. Indeed, once landed, retreat is impossible. Americans do not surrender.” He stressed that a pint of sweat saved a gallon of blood and concluded, “On our victory depends the freedom or slavery of the human race. We shall surely win.”9 The men were issued the password of the day to prevent friendly fire incidents once ashore. To the challenge “George,” a soldier would answer, “Patton.”10

Patton steeled himself for whatever lay ahead. “My whole life has been pointed at this moment,” he wrote his wife. “All I want to do right now is my full duty. If I do that, the rest will take care of itself.” To a friend he wrote, “We shall be completely successful.” But a small quiver of doubt was palpable: “If we are not, it is not my intention to live to make excuses; however, I feel very healthy for a dead man.”11 Patton had done everything possible to ensure success, from training his troops to requesting all needed equipment, in only a few months’ time. Only hours before the landings were to take place, he spotted an imperfection that he felt might hinder the operation. Shown a French-language pamphlet intended to be dropped by the thousands over Moroccan cities, he noticed it lacked accents on certain French words. He quickly gathered his staff and ordered them to add the accents. “Or do you expect me to land on French soil introduced by such illiterate calling cards—Goddam it?”12

If the poorly worded pamphlet irritated Patton, a message from the president infuriated him. As the fleet arrived off Morocco well before sunrise on November 8, a BBC broadcast from Franklin D. Roosevelt to all of North Africa asked the Vichy regime not to obstruct the assaulting forces. The broadcast had been timed to coordinate with the assaults on Oran and Algiers, which took place hours earlier than Patton’s landing. Patton worried that the broadcast blew his cover before a single landing craft had headed to shore.13

Somewhere in the darkness, Patton’s troops clambered down rope nets into those landing craft. Some overloaded soldiers fell into the water, never to reemerge. H-hour, the time for the assault, approached—4:00 a.m.—and passed without action. The Navy kept delaying as coxswains struggled to get their landing craft into formation for the push toward the shore. Patton anxiously watched the transports line up, visible only by their colored lights. Over the radio, he heard the naval commanders speaking in code, organizing the fleet: “All my chickens are here, am holding them.” Then an American submarine cruised up and guided in the destroyers. All was quiet.14

The Navy had delivered Patton’s force to the battlefield on time and in the right spot, despite his doubts. A month before, he had predicted that the Navy would break down in the first five minutes and the Army would have to provide the victory. “Never in history,” he had told his Navy comrades, “has the Navy landed an army at the planned time and place. If you land us anywhere within fifty miles of Fedhala [sic] and within one week of D-day, I’ll go ahead and win.” When poor weather threatened his landing, he radioed Eisenhower that if he could not land on the west coast of Africa, he would land somewhere else, even neutral Spain. But the weather held, and the Navy had done its job. Now it was Patton’s turn.15

The general gathered a group of Army officers together for one last pep talk. “All I can promise you is that we will attack for sixty hours, after that, we will attack for sixty hours more.” He told them if the French fought back, they would do so at their own peril. If they chose not to, his men should kiss them on their cheeks and move on. He explained that soldiers could walk faster forward than backward, alluding to his disdain of retreat. “Gentlemen,” he concluded, “the weather is delightful and so are our prospects. Prepare at once for action.”16

The speech revealed the single question that dogged Patton, as it did all the men in landing crafts and every commander as far away as the War Department in Washington: Would the Vichy French fight? Would there be an exchange of wine and chocolate bars on the beaches or of hot lead? The French held no love for the Germans, but since France’s surrender to Germany in 1940 they were subject to German orders. In exchange for Hitler giving the French a portion of their own country to police—Vichy France, which included French territories like Morocco—the Vichy regime swore to defend their country from Germany’s enemies. The Americans hoped the French would join them in the fight against the Axis, but as the soldiers and sailors headed ashore, no one, not even Patton, knew what would happen once the boats touched sand.

The radio crackled and Patton heard from General Harmon at Safi: “Batter up.” Bad news: his troops were under fire. An hour later Patton eyed a single searchlight on shore shoot into the sky—the prearranged signal for no opposition—then turn to the beach. The sun rose as the destroyers opened fire, providing covering fire for the men spilling out of their landing craft. To Patton, their tracer fire looked like fireflies. Four French ships steamed in to challenge the U.S. Navy, commencing a duel. General Lucien Truscott radioed in: “Play ball.” He needed naval firepower to knock out a coastal battery on Mehdia beach. Patton’s watch showed 7:13 a.m.17

Patton prepared himself to go ashore at for 8:00 a.m., but his favorite pistols were missing, waiting for him on his landing craft, which had just been swung out over the water by two davits. Not wanting to wait until he was bobbing toward the African shore to strap on his weapons, Patton ordered Staff Sergeant George Meeks, his African American orderly, to retrieve the pistols. He had purchased his .45 caliber automatic Colt “Peacemaker” in 1916, just before departing for Mexico to take part in General John J. Pershing’s hunt for Pancho Villa. Patton had an eagle carved into one of the ivory grips. After a shootout at Rubio Ranch in which Patton helped kill one of Villa’s commanders, Julio Cardenas, and two of his men, he cut two notches into the grip, denoting the two bandits he helped kill. Patton kept an empty shell in the chamber under the hammer after accidentally wounding himself when a holstered Colt discharged as he stomped his feet, searing his thigh. He wanted a second pistol after having to reload his Peacemaker in the middle of the Rubio Ranch shootout, purchasing the Magnum, which he called his “killing gun,” in late 1935. Patton wore the pistols, both with ivory grips and his initials carved onto them, on a belt that included a compass in a handcuff case and an extra cartridge in a rectangular case.18

As soon as Meeks brought Patton the holstered pistols, three French warships appeared, driving hard for the fleet. The Augusta accelerated and opened fire with its rear gun. The subsequent blast bent Patton’s empty landing craft in half, and it had to be dropped overboard.19 Patton lost all his personal items except his pistols. Barely batting an eye, he remarked to his bodyguard, “Such are the fortunes of war. . . . Let’s ...