![]()

PART I

The Birthplace of the Green Revolution

![]()

Chapter 1

Why the Yaqui Valley? An Introduction

PAMELA MATSON AND WALTER FALCON

There are few agricultural regions in the world more interesting and important than the Yaqui Valley in Sonora, Mexico. The Yaqui River Basin has supported agriculture for many centuries, but the story we focus on is modern. The valley is the birthplace of the green revolution, and it is now one of the most intensive agricultural regions of the world, using irrigation water, fertilizers, constantly improving cultivars, and other inputs to produce some of the highest yields of wheat anywhere. It is one of Mexico’s main breadbaskets and also a global supplier of seeds and grain. In this, the Yaqui Valley provides a story of agricultural and economic development that is emulated and reflected the world over. But over the past several decades, its story has also become one of environmental, resource, economic, and social challenges related to water resources, air and water pollution, impacts of global environmental and policy changes, human health concerns, biodiversity conservation, and climate change. As these two story lines have merged, this region has had to evolve and change. It is this story of early steps in a sustainability transition—a transition at the interface of environment and development—in which we engaged through our integrative research and outreach. It is this story that we hope to tell in this book.

Sustainability is a complex concept, one with multiple definitions and goals. In its report titled Our Common Journey, the National Research Council (NRC 1999) defined sustainability broadly as the goal of meeting the needs of people today and in the future while (and by) protecting the life support systems of the planet. As we use it here, in the context of transitions in the Yaqui Valley, we encompass the goals of improving and enhancing food, fiber, and potentially even biofuel production, protecting the economic and social welfare of the people of the region, and sustaining its resource base and environment on land and in the sea.

Worldwide, the sustainability challenges of agriculture and food security are enormous, given the need to feed a still-growing human population that is likely to plateau at near nine billion by the middle of this century. Today, in 2010, scientific concern about this challenge can be seen in the pages and special issues of Science and Nature magazines, among many other venues. Taken together, the growing food demand associated with population growth; alleviation of hunger and increased consumption of meat and dairy; the increasing competition of agricultural lands for other uses; the increasingly clear evidence that agriculture drives negative environmental and human health changes at local to global scales; and the growing, serious concern about the effects of climate change on crop systems have called for a worldwide research effort to address agricultural sustainability and food security (for recent reviews and analyses of these issues, see IASSTD 2009; Royal Society 2009; Godfray et al. 2010; Federoff et al. 2010; NRC 2010a, to name just a few).

Agricultural sustainability challenges potentially can be addressed through a variety of approaches, including, for example, new breeding technologies, including the development of genetically modified crops; new kinds of integrative crop-livestock systems; precision agriculture (both “high tech” remote sensing and computer-based mechanized approaches as recently described in Gebbers and Adamchuk [2010] as well as lower tech approaches that use information to increase input efficiency); agroecosys-tem approaches that seek to use soil, water, and light resources to maximize and increase efficiency of production while reducing environmental negatives; and new, more efficient aquacultural systems. While all of these can contribute to sustainability goals, none can do the job everywhere nor be implemented overnight to achieve sustainability. In the Yaqui Valley as in most agricultural systems, sustainability is not an end point that can be defined or that is likely to be achieved in the near term, but rather a process of developing options and making choices that increasingly honor these multiple goals, and that make progress toward all of them. The Yaqui Valley is still in the early phases of its transition to sustainability, but these first steps are important.

Our story is about these seeds of a sustainability transition in an agricultural region, but the things we’ve learned—about implementing win-win opportunities, or knowledge systems for sustainable development, or vulnerability analyses of human-environment systems, for example—are relevant to many other sustainability efforts outside of agriculture. Likewise, what we have learned about the role and contributions of multi- and interdisciplinary research in developing options and supporting implementation of them speaks to sustainability science and development efforts more generally.

The Story of Agriculture in the Yaqui Valley

In our research in the Yaqui Valley, our primary focus was the dynamic human-environment systems in irrigated agriculture and nearby land and ocean systems, as they functioned between 1993 and 2008 at the end of the green revolution and the beginning of what Gordon Conway calls the “doubly green revolution” (Conway 1997). The longer story of agriculture in the valley is, however, of importance to the more recent past; chapter 2 provides a detailed history, but an abbreviated version will be useful in this introduction to the book.

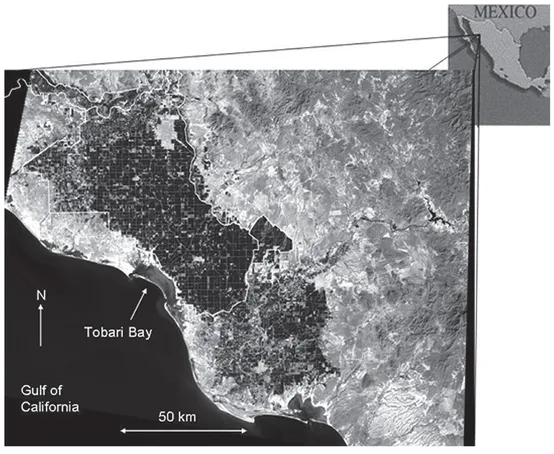

Located on the northwest coast of mainland Mexico, bound by the Gulf of California to the west and the Sierra Madre Occidental foothills to the north and east (fig. 1.1), this productive coastal plain has been inhabited for thousands of years by the indigenous Yaqui Amerindians. For centuries, the Yaquis fought against and ultimately lost to the encroachment of Spanish and Mexican colonists interested in their fertile lands and silver resources. The introduction of foreign investment and irrigation in the 1890s and early 1900s laid the foundation for what would be the most intensively irrigated agricultural land in Mexico that now covers 233,000 hectares. The establishment in the 1930s (and thereafter) of a substantial number of ejido (collective) farming units, in addition to private landowners, the Yaqui Amerindians, and foreign investors, made for unusually diverse groups and interests within the region.

In the mid-twentieth century, the Mexican government and the international development community identified the Yaqui Valley as an appropriate center for agricultural research and development, given that it is agroclimatically representative of about 40 percent of wheat growing areas in developing countries. Led by Norman Borlaug and an international team of scientists, the wheat research program promoted intensive technologies such as new high-yielding crop varieties, large-scale irrigation, fertilization, and pesticides. The results—a dramatic increase in grain production that supported Mexico’s transition to self-sufficiency in wheat production and the direct transfer of semidwarf wheat technology to South Asia in the late 1960s—gave the valley its recognition as the home of the green revolution for wheat. However, agricultural development in the region was not the only story of change. Rapid population growth focused in cities, major development of fisheries, the engagement of the international conservation community in the adjacent oceans, the development of coastal aquaculture, and the rapid increase in livestock operations were likewise a part of the story in the valley and surrounding regions. By the time our research team entered the picture, these changes were under way.

FIGURE 1.1 Location of the Yaqui Valley, Sonora, Mexico

The period of the 1990s and early 2000s, however, involved further changes, and many of them were especially challenging for Yaqui citizens, especially farmers. An eight-year drought (1997–2004), coupled with questionable irrigation procedures, literally drained the valley’s irrigation reservoirs dry, and raised questions about vulnerability of water resources in the context of future climate changes. Fertilizer use increased, but so too did nitrogen losses in the form of greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions to the atmosphere as well as water pollutants. Crop diseases and pests came, but rarely went, causing for example the complete loss of soybeans from cropping rotations. Major changes in Mexican macroeconomic policy, Mexico’s entry into the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA), and booms and busts in international commodity markets created new forms of economic uncertainty in a valley that had previously led a very “policy-protected” life.

Constitutional changes expanded the ways in which ejiditarios (small communal farmers) could rent and sell their land, but also made them more vulnerable to other market-oriented policies on credit and fertilizer. Many aspects of the irrigation system were decentralized from federal to state and valley organizations, giving local farmers more authority, but also more responsibility for the ways in which water systems were managed. Agricultural extension shifted from federal hands to those of farmer unions. Attempts at diversification into fruits, vegetables, livestock, and aquaculture solved some problems, but created other ecological and economic dilemmas in the process.

These physical, economic, environmental, and social changes greatly complicated life in the Yaqui Valley. They also complicated our research efforts, but at the same time made those efforts more interesting and valuable. Change was happening so rapidly that Yaqui residents eagerly sought out the results of our studies, but the fast pace also made it difficult to establish sensible research priorities, let alone to fund them. For all of its limitations, however, the research program reported on in this volume was quite remarkable. Much place-based research is based on a single snapshot in time. We do not have a complete historical movie of the Yaqui Valley, but we do have a fairly complete ten-plus year video clip.

Integrative Research in the Valley

The choice of the Yaqui Valley as the focus of our research effort was in some ways just good luck (see the preface for more on the origins of the project), but after the fact, it proved to be an excellent choice. It is a region small enough to be understood, yet large enough to be interesting. It is a region that represents the kind of high-productivity, surplus agricultural system that is key to feeding billions of people; indeed, we explicitly chose this kind of system, in contrast to small scale, localized, or subsistence systems, even though sustainability decisions in the valley were likely to be more complicated and externally controlled. It is a region that makes connectivity—between land and ocean, land and air, water and food, country and country, peso and dollar—very obvious.

The Yaqui Valley was also an excellent choice for our research because it has been a focus of disciplinary research, mostly agronomic, for decades. As the location of the primary field station of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), one of the major centers of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) system, it has accumulated more than thirty years of knowledge. CIMMYT field research and survey data on valley farmers and on wheat technology provided a wonderful base from which to build our research. The federal government has also been conducting agricultural research through the National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture, and Livestock Research (INIFAP). INIFAP operates eight regional agricultural research centers throughout Mexico, including one in the Yaqui Valley (Research Center for the Northwest Region, Mexico [CIRNO]). CIRNO works closely with CIMMYT to further research on genetic improvement, production technology, pest management, new cropping options, and irrigation technology. Also, the farmer-owned Agricultural Research and Experimentation Board of the State of Sonora (PIEAES, known locally as the Patronato) receives breeder quality lines from CIRNO and sells them to farmer organizations who produce registered seeds. And perhaps the most important actors engaged in agriculture research are the farmers themselves—particularly a set of innovative farmers that routinely collaborate with CIMMYT and CIRNO scientists—and the credit organizations that represent them. The National Water Commission (CNA) also carries out research in support of water for irrigation, and universities such as the Sonoran Institute of Technology (ITSON) and the Monterey Technological Institute conduct research in agronomics and related areas, especially natural resources and coastal zone management.

With all this research strength, one might wonder what our multidisciplinary team of researchers from the United States and Mexico could offer. The answer, quite simply, was an integrative systems perspective. We started with a focus on the human-environment systems of the place, and an interest at the interface of crop yields, economic gains, fertilizer use, and environmental implications. Before long, as our understanding of the valley’s challenges became clear and as our team grew, we focused on irrigation management, aquaculture development, Mexican and international economic and agricultural policies as they affected the valley, environmental links between the irrigated valley and the coast and the Gulf of California, diversification of crops, and climate change and vulnerability in the agricultural sector, and others. It did not take long to see that many if not all of these issues were connected, and that the Yaqui Valley was an excellent place to analyze and understand them as a system, perhaps doing something to help manage them sustainably. We did not start with the intention of developing a broad, decade-long analysis of sustainability in the valley, or of engaging with decision makers across such a broad range of issues, but our research took us there. Over time we saw that there is no better place to evaluate where progressive agricultural systems were headed technologically; to view the effects of globalization and the impact of NAFTA; to make the connections between agriculture, resource use, and environmental impacts; to engage in efforts to share new knowledge in decision making; and to understand those knowledge-to-action linkages, than in the Yaqui Valley.

This work was completed through the support of many different projects by many different funding organizations (see the preface for details). The need for multiple funding sources complicated the knowledge-generation process. Some critical pieces were never funded, frustrating our desire to understand a more complete story and provide more useful information. The time perspective and the long-term nature of the inquiry were crucial, but also called for an almost constant search for funding. Learning and modification of ideas took place in laboratories, at the experimentation station, on farmers’ fields, in scores of meetings with growers and other decision makers, and in regular team meetings both in the Yaqui Valley and at Stanford University. While the research elements at times appeared disjointed, they emerged logically and often built upon each other as they progressed. The individual subprojects were well done, and their outcomes have stood alone as published research papers as well as new models, tools, and management approaches. While it may be that these individual products yielding from these projects have mattered most to decision making in the valley, it is the sum total that best tells the story of the valley in transition.

In subtext, this book also tells the story of a changing and growing team of researchers trying to move from simply understanding the challenges being faced by the people and ecosystems of the valley to assisting in addressing those challenges. How, over time, did agronomists, biogeochemists, economists, ecologists, engineers, oceanographers, geographers, hydrologists, and other scientists decide to work together to analyze and help solve problems? How did we interact with farmers and other decision makers of the valley, and how did the flow of information among us all determine which problems were chosen and why? How was the research funded as problems and funding agendas changed? And what research lessons were learned, both positive and negative, from a research effort that covered more than a decade and cost several millions of dollars?

The relatively long-term extent of the project proved the importance of working in one place continuously, and for a long time; had the inquiry stopped in 1998, or even 2002, our understanding of the interface between economics and environmental issues of the valley would have been substantially more limited. Nevertheless, it is clear that the full story of the Yaqui Valley is not ours to grasp. The valley continues to change, and some, perhaps much, of what we learned during our years of joint study and engagement has become outdated. We seek, therefore, to share through this book some of the general learning and more generally useful information, perspectives, and research approaches, along with the specific knowledge that was useful at a given time and place.

Organization of the Book

We tell the story of the last few decades of agricultural development and environment in the Yaqui Valley in several parts. In this first section, we introduce the reasons for working on these issues and in this valley, and, in chapter 2, we set the valley in historical perspective. Then, in the second part—chapters 3 through 7—we tell the interdisciplinary, integrative stories that motivated much of our work. We asked, for example, whether win-win-win solutions, for economics, agronomics, and environment, are possible in the wheat fields of the Yaqui Valley, and what would be needed to make them a reality (chap. 3). This is the project that got us started, and it eventual...