![]()

1.

If It Can Happen Here

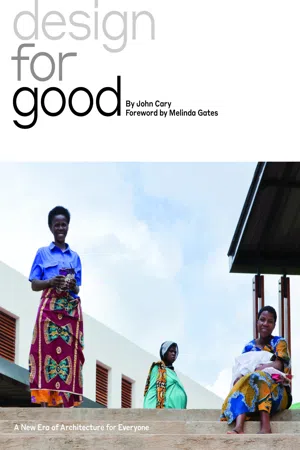

The Improbable Story of Rwanda’s Butaro Hospital

Butaro Hospital in Burera, Rwanda, by MASS Design Group, Partners in Health, and Rwanda Ministry of Health; completed in 2011.

Michael Murphy remembers the night well. On the eve of his final semester presentation during his first year at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Murphy quietly ventured across campus to sit in on a lecture unrelated to his pressing schoolwork. It was December 1, 2006, World AIDS Day.

The lecturer was the global health pioneer Dr. Paul Farmer, cofounder of Partners in Health (PIH), an international nongovernmental organization. A year earlier, while living in South Africa, Murphy had read Mountains Beyond Mountains, Tracy Kidder’s popular book on Farmer, an uncompromising humanitarian, and the organization he cofounded. Before ultimately deciding to go to architecture school, Murphy had even researched job openings at PIH. Then and now, he faced the dilemma many of us have—how do you get access to an organization that you admire? A friend who wasn’t even in graduate school with Murphy had alerted him to Farmer’s lecture, so off he went.

Murphy was preparing to pull an “all-nighter,” a rite of passage in architecture school, to work on his final project. He had done so innumerable times that semester, and each time, he had a little ritual of wearing his father’s old Poughkeepsie High School Crew sweatshirt. Murphy recalls: “I looked terrible, ragged, unkempt, wearing this paint-covered sweatshirt.”

Soon after Murphy settled into his seat, Farmer said, “We’re building housing.” Murphy had never thought about housing as a health-care priority before. “That really piqued my interest, and I sat up, thinking, ‘Wow, this guy is building housing for people in really poor communities because he wants to provide better health care.’ It instantly made sense: housing is a social determinant of health.”

View of the countryside surrounding the Butaro Hospital.

Farmer has a practice of patiently hearing out every person in line to talk with him after a lecture or panel discussion. “He’s very, very kind,” Murphy tells me, “and I think he was really energized that night by all the students who came up to him afterward, saying ‘I want to mention my project to you.’ He just waits for everyone to finish. That access was surprising; he was just so receptive.”

Eager to work for any architecture firm working with Farmer, Murphy asked which firms Partners in Health had experience with. After all, Farmer had described building clinics, hospitals, housing, even roads. “I drew the last clinic on a napkin,” Farmer told him. Here was a pioneer in global health who was undertaking significant building projects, and he had effectively never worked with an architect. Murphy was astonished, unaware at the time how little the practices of architecture and design intersected with global health and development work such as Farmer’s.

At the end of their conversation, Farmer gave Murphy his e-mail address. By 9:30 p.m., Murphy was back at his desk and writing an e-mail to Farmer rather than working on his final project. “I sent him a message, and he wrote right back to me. So I sent him another e-mail, and he wrote right back again,” Murphy recalls. “We were e-mailing about gardens and fishponds at his hospital in Haiti, and just talking about the beauty of gardens. I couldn’t believe that this guy was writing back to me.” Murphy remembers feeling a little starstruck but also inspired by the access to Farmer.

Murphy finally turned back to his studio project. He was tasked with squeezing a public pool into a bizarre, awkward site near a train station in Brookline, Massachusetts. “It was meaningless. I was also totally failing on the project,” he recalls. But Murphy finished the project, and kept in touch with Farmer. In the summer of 2007, just six months after meeting him, Murphy accepted Farmer’s invitation to visit Rwanda, one of the countries in which PIH had recently started to work.

Twenty-seven at the time, Murphy had never been to Rwanda, a landlocked East African country known for its gorillas and volcanoes and for the brutal civil war that had led to a horrendous genocide in 1994, just over a decade earlier. In its healing and under the leadership of President Paul Kagame since 2000, Rwanda had been transforming itself into a center for innovation in health-care delivery. PIH signed on as a crucial partner of Rwanda’s Ministry of Health in 2005.

Mere hours after Murphy arrived in the capital city, Kigali, a doctor named Michael Rich picked him up for the two-hour drive to the organization’s main office in Rwinkwavu, a town in eastern Rwanda. As he drove, Rich effectively said to Murphy, “What are you doing here? You’re clearly not here for long enough to make a difference.”

Murphy would learn during their drive that Rich’s father was a contractor who had done huge building projects. Rich himself had built his own house out of mud bricks. So Rich uniquely understood construction and building and had done a lot of thinking about the planning of PIH’s medical campus in Rwinkwavu.

Speaking of Rich, Murphy tells me, “Michael is very talented in a design sense. He was understandably asking, ‘What’s this twenty-seven-year-old architecture student with barely one year of experience doing here for a few weeks? What value is that going to provide?’” Murphy concedes, “He was very skeptical. I would have the same feeling if I was bringing on someone like that today.”

Over many months and years, the two developed a strong relationship built on trust, hard work, and mutual commitment to PIH’s goals. Murphy now counts Rich as one of his dearest friends and biggest advocates. “It was in that first couple of weeks, living with a bunch of doctors, trying to make myself useful, that I really built these relationships,” Murphy explains. “It also helped me at least start to hone in on what would be useful for me to do.”

Murphy’s time in Rwanda that summer was spent between Kigali and Rwinkwavu, with visits to other PIH field sites. The organization had an array of projects and facilities, and Murphy tried to help out wherever possible. Perhaps most significantly, it was then that he met a Rwandan builder named Bruce Nizeye, PIH’s head of infrastructure at the time. Nizeye was doing everything from building a large training center and a laundry facility to putting in a garden and a fishpond in one of the other health centers. Murphy recalls innumerable small projects that Nizeye, his brother Fabrice Nusenga, and an army of local artisans tackled day in and day out. They were working out of a few old warehouses on the PIH campus, left over from a mining company that used to be there.

“I was just so inspired. Bruce and his crew were thinking about architecture completely differently from how I ever had. He was literally making everything—working with carpenters to make furniture and metalworkers to weld windows, among many other things,” Murphy recalls. “But being so young and so new to architecture, I wasn’t burdened by the way architecture is made in the U.S. enough to understand exactly how different it really was. There, if someone needed a chair, Bruce made a chair.”

Nizeye’s focus on local labor and local materials made a profound impression on Murphy, and it would become a hallmark of Murphy’s work and the nonprofit he would go on to found. Murphy stuck close to Nizeye, working on the laundry facility and other small projects, before returning to the United States and to school.

Design team members discuss progress and future development opportunities on the Butaro Hospital campus.

I met Michael Murphy shortly after his return from that first fateful trip to Rwanda, for no other reason than that he was dating a summer intern at the nonprofit I directed in San Francisco. I had heard a lot about Murphy by the time the pair waltzed into the fourth-floor loft that our organization occupied.

When Murphy and my intern, a Bay Area native named Marika Shioiri-Clark, told me they were returning to Rwanda to design and build a hospital, my first thought was, “This is a terrible idea.” In my work domestically and knowing of innumerable other examples internationally, I had seen well-intentioned designers parachuting into unfamiliar places to “help,” only to be crushed by the complexity of conditions they never could have anticipated from a distance. This seemed all the more probable for a couple of Ivy League graduate students. What could they possibly have been thinking?

At the time, most work of this type was conceptual, and much of it was small in scale, if it had even reached the point of construction. Schemes for shipping-container clinics were especially prevalent. Again, all well-intentioned but difficult to execute for a whole host of reasons.

Thank goodness Murphy and Shioiri-Clark didn’t listen to me.

The pair and a group of classmates launched MASS Design Group, with MASS standing for “Model of Architecture Serving Society.” Along with classmate David Saladik, Murphy and Shioiri-Clark went to Rwanda that winter. They spent their school break sketching possible schemes for a hospital in the Burera District, which at the time was home to over 340,000 people and barely one functioning clinic. They then returned to Harvard, recruited a larger group of students, and spent many cold Boston nights and weekends designing the hospital.

After weeks of work, the team settled on a barrack-style building for the hospital. Even Murphy was underwhelmed. “It was not a good design; we just didn’t know what we were doing,” he recalls. Murphy shared the design with Michael Rich, who told him, “I really don’t think this is what you want to show. It’s not the kind of inspiring architecture that we were hoping for.” Murphy knew R...