![]()

Chapter 1

The Three Waves That Are Changing Cities Forever

Three major trends are affecting the development of tomorrow’s cities. These three waves will crash with different effects in cities of the developed and developing world. But in the end both types of cities seem destined to develop dramatic similarities in future decades.

Wave One: The Worldwide Rural-to-Urban Migration

We are in the midst of the largest human migration in history. The scale of the current migration dwarfs the 19th-century rural-to-urban migration, which saw millions move from the European countryside to European cities or to the growing cities of North America. Now we are talking of a migration that affects billions and is global in scale. We are experiencing a tsunami of migration that includes moves from rural areas to urban areas within the same country and from rural areas in one country to urban areas in other countries entirely; in the end, it’s all about movements to the city.

Rural-to-urban migrations have gone on since the birth of cities, which means for about ten to fifteen thousand years. It was then that agriculture emerged, and with it the need for communal practices in fixed locations with a rudimentary division of labor. Theorists have speculated that these agricultural practices emerged consequent to the radical and rapid climate changes brought on by the recession of the most recent ice age. Humans at that time, facing a Middle Eastern landscape that was rapidly becoming warmer and drier, realized that carbohydrate-rich grains could be cultivated rather than just gathered and that crude mechanical means of preparing these grains (threshing, grinding) would make otherwise unpalatable seeds digestible.1 Cities that emerged at this time were organically suited to the scale of the agricultural enterprise: Urban villages were numerous but small, ordered in conformance to an area’s agricultural capacity and limited by the physical constraint of how far village residents could walk between home, workshops, and fields. This rational ordering of the agricultural landscape is still echoed in night pictures of the American corn belt, where small towns are evenly spaced.

The Industrial Revolution spurred the growth of ever larger cities. Whereas agrarian landscapes necessarily disperse a decentralized population across the land, machine-based industrial cities seem to perform better economically the larger they grow. (Chinese cities may be testing this hypothesis. We shall soon see.)

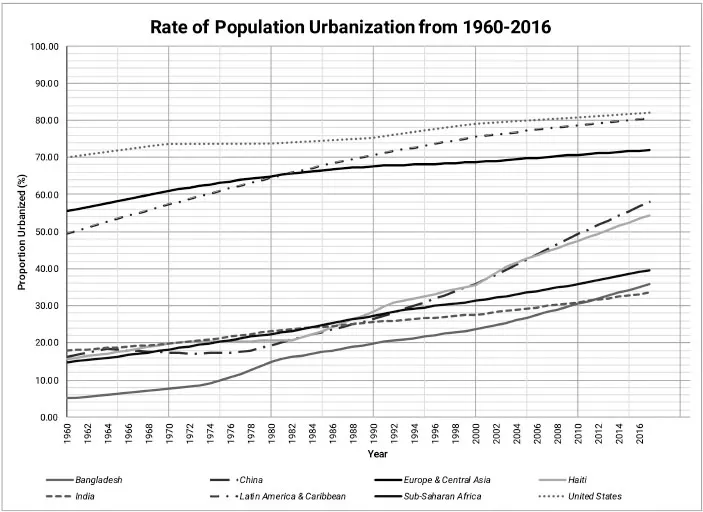

By now the process of urbanization in the United States has slowed to a steady rate of 2 percent per decade, whereas South America, somewhat surprisingly, has essentially caught up with the United States. Asian nations, especially China and Bangladesh, are seeing tremendously rapid urban growth, whereas Africa, starting later and with more diversity from country to country in its rate of urbanization, leaves the final percentage of its future urban population more open to question.2 This African trend is enormously important, given the fact that if current population trends continue, Africa will soon supplant Asia as the most populous continent on the planet. The role that cities can and should play in Africa, and the significance of this shift for Africa and for the rest of the planet, will be returned to later in this text.

For many parts of the world, India and Pakistan notably, rural-to-urban migrants often skip their own country and land in major cities around the world. Nearly seven million Indians leave their rural settings each decade for big cities in other countries, largely in the United States and Great Britain. There are well-established communities of South Asians in those two countries, as there are in the United Arab Emirates, where they are needed as workers.3

Figure 1-1 Population in most of the world is trending toward roughly 70 percent urbanization by 2060. The biggest question is what will happen in Sub-Saharan Africa. (Source: World Bank)

Altogether there are about a quarter billion people on the planet who have moved from one country to another, and most of these people moved from rural areas where opportunities were few to large cities where opportunities were more numerous.4 More than 60 percent of these global migrants who left their home countries landed in developed countries, and nearly all found a home in cities. For example, foreign-born residents make up 2.3 percent of the population in U.S. rural counties, compared with nearly 15 percent of urban counties.5 This migration trend is accelerating, with a doubling in the rate of global migration between 2000 and 2010.

According to the UN Department of Social and Economic Affairs, more than six billion people will live in cities by 2050, just about twice the current number, or approximately two thirds of all people on Earth at that time.6 If the trend lines continue without interruption, by 2100 there will be as many as nine billion people living in cities worldwide, and no more than three billion rural dwellers. At that time approximately 80 percent of global population will probably live in cities. These numbers are of course uncertain, as history has a way of changing trend lines in various ways. But the trend toward cities, no matter the rate, seems unalterable.7,8

When we consider the economic motivations for increasing global levels of immigration, we often focus on the supply side, that is, the number of immigrants who want to leave their own less developed country for life in a more developed one. This is a reasonable focus, but it obscures the other side of the coin: Developed countries need immigrants more than immigrants need developed countries, as without immigration their economies will slow or fail. They will slow or fail because women in developed countries are having far fewer babies than they used to, creating a shortage of working-age citizens to fill the many job slots of a modern economy.9

In his excellent book titled Arrival Cities, Doug Saunders shares a key insight that a connection usually endures between migrants to the city and the rural village from which they came.10 Often migrants maintain and even expand homes in their home village and can sometimes provide significant economic support for their home community. He cites an example of a proprietor of a sub shop whose existence in Toronto is modest, but with the profits he makes from his family business he maintains a large house in Pakistan where he employs a number of people in the village just to maintain his home while he is away. This is an interesting insight, as it helps show that rural life is increasingly connected to what goes on in our cities and that to consider rural areas as distinct and separate from urban areas is not accurate. The network of relationships between the city and the countryside is stronger than ever, he says, and even residents of rural zones are rapidly separating themselves from their traditional agrarian pursuits.

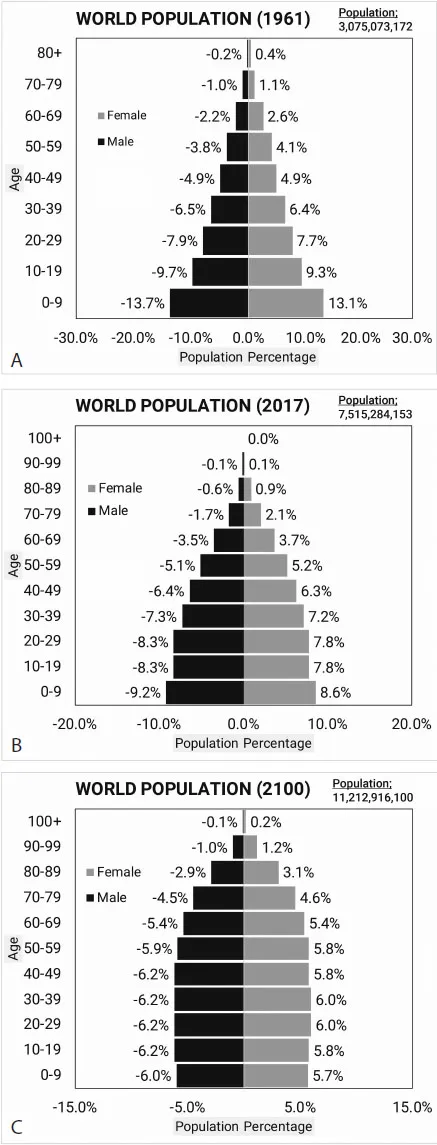

Given declining fertility rates, the populations of developed countries would soon be (or in a few cases already are) in decline, were it not for immigration. Declining fertility rates may not seem to be a cause for concern until you consider the fact that as birth rates decline, the proportionate share of older adults in comparison to other age groups must necessarily increase. Absent immigration, many developed countries would soon lack enough workers in their most productive ages to keep an economy afloat, and, not insignificantly, to take care of all these older citizens who would then need labor-intensive health care. The current populist revolt against immigration in the United States and the inability of the U.S. Congress to agree on a sane immigration policy is already creating imbalances of this type, imbalances that are likely to get much worse.

Doug Saunders shows that the motivations for these migrations were remarkably similar. Migrants were motivated to move by the constrained opportunities in their home rural areas and by expanded possibilities in national or extranational urban areas. He maintains that rural-to-urban migrants, no matter what country they come from, have more in common than not. They have a narrow focus on improving their lives via a “dotted line,” which carries them first to “arrival cities” and then to a life that, as much as possible, satisfies their life goals.

Effective urban design for immigration, as we shall see in later chapters, is design that creates space for immigrants to first arrive, then to gain a foothold in which to work and serve the needs of other citizens and immigrants, and in the process support their family members both near and far.

Wave Two: Collapsing Birth Rates

Given current trends, by 2060 the cities of the world will stop growing, on average, and many will begin to shrink. With the possible exception of cities in Sub-Saharan Africa, which may continue their growth beyond that date, declining birth rates make this inevitable. Shocked? Doubtful? The evidence provided below will back this up, but for now hold back doubts and just imagine. All of us, without exception, have grown up in a world where we naturally assume that population will keep growing with no end, and our cities with it. Knowing this we were inevitably sifted into one of two camps: the pessimists and the optimists. The pessimist camp includes those who think that unending population increase will eventually crush the planet’s capacity to produce food, leading to worldwide famine and ecological Armageddon.11 The second camp takes the opposite position, suggesting that those in the first camp are making the same mistake Thomas Malthus made in the 18th century. It was he who first predicted mass starvations consequent to overpopulation.12 These starvations never came, at least not in the way Malthus imagined.13 New farming methods and global trade overcame those obstacles. The optimists believe that no matter the constraints, humanity will eventually find the technological means to overcome them; as it was in the past, so will it be in the future. This “techno-enthusiast” camp even suggests that other planets are ripe for colonization when and if Earth becomes too crowded or when and if its resources are exhausted.14 However, that conversation has recently changed. There is now growing evidence that the seemingly parabolic rise of global population has slowed and may, during the working lives of those just starting their professional career, stabilize and perhaps even begin to decline. The cause of this slowing of global population growth is attributable to one thing. It is not starvation, it is not war, it is not disease, and it is not poverty. It is simply that women around the world are choosing to have fewer children—so many fewer children that global population may even, within 40 or 50 years, start to decline. The cause of this decline? It appears to correlate with the rise of cities more than with any other factor. If true, we clearly need to change our way of thinking about cities.

The implications of this emerging trend are enormous. Combined with rural-to-urban migration, we can expect cities to grow very rapidly in the near term—both from migration and from the long lag time before current fertility rate15 declines seriously reduce global population numbers. These changes will occur during the same decades that other dramatic economic and technological disruptions are affecting cities (think of the rise of Uber and Lyft, the switch to electric cars, roads filled with self-driving vehicles, the automation of service industries, continued wage stagnation, artificial intelligence, ever greater inequality, on and on). But is this really true? Will cities really stop growing? Can global population actually decline and city populations with it? That soon? The reader deserves more evidence before deciding.

When Did the Birth Rate Decline Start?

Fertility rates have been declining in the developed world for over two hundred years. In 1810 the U.S. fertility rate was approximately 7.0 births per woman. At that time more than 80 percent of all Americans were rural farmers. By 1850, only 50 years later, fertility rates had dropped dramatically to 4.5 births per woman. At that time farm employment had dropped to the point where only 50 percent of all Americans worked on farms.16,17 By then, the U.S. shift to a majority urban population and declining fertility rates was well under way. This is an early example of the phenomenon but a typical one. The correlation between increased urbanization and decreased fertility is very strong no matter where you are in the world.

A notable exception, and a temporary one, was the post–World War II baby boom, when U.S. fertility rates jumped from 2.2 per woman in the 1930s to 3.8 per woman in the early 1960s (the very peak of the baby boom). This coincided with the rapid expansion of U.S. metropolitan areas, typically spreading across former farm fields in the form of auto-oriented sprawl.18 The boom was short lived, however, with U.S. fertility rates returning to their longer-term decline, in line with continued urbanization, by the seventies. In 1975 the U.S. fertility rate went below the replacement rate of 2.1 live births per woman for the first time, where it has stayed since.19,20 It was in this same decade that urbanization rates in the United States approached 80 percent. Currently the U.S. birth rate is 1.84 live births per woman, a historic low and well below the replacement rate,21 and the rate of urbanization is 82 percent. In Canada, where more than 80 percent of its citizens live in cities, fertility rates are even lower at 1.6 live births per woman. Absent immigration, the populations of both countries would soon decline.

Each Continent Is Different: Europe

The fertility rate is declining at different rates in different countries, typically in parallel with increases in urbanization. Europe, much like the United States, had a very high fertility rate in 1800s, ranging from a high of 7 births per woman in the Ukraine to a low of 4.5 in France.22 By 2015, when Europe was 77 percent urbanized, the fertility rate had dropped to a low of 1.36 births per woman in Poland and to a “high” of 1.91 in Sweden.23 As mentioned previously with reference to the United States and Canada, with such low birth rates, were it not for immigration many European countries would experience population declines. This is notably the case in Italy, where an aversion to accepting immigrants, combined with a higher than typical aversion on the part of Italian women to wed and rear, caused Italy’s population to drop in 2016, modestly, for first time in the modern era.24

Figures 1-...