This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Unbeknownst to most of the city's inhabitants, a rural community of garbage workers once existed on a now-vanished island in New York City. Barren Island was a swampy speck in Jamaica Bay where a motley group of new immigrants and African Americans quietly processed mountains of garbage and dead animals starting in the 1850s. They turned the waste into useful industrial products until their eviction by Robert Moses, in the name of progress, in 1936. Barren Islanders built businesses, fought fires, demanded a public school and worshipped at churches as they created a quintessentially American community from scratch. Author Miriam Sicherman tells the story of a Brooklyn neighborhood lost in the annals of New York City history.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Brooklyn's Barren Island by Miriam Sicherman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

EARLY HISTORY, LANDSCAPE AND POPULATION

The big thing on Barren Island was the tides.

Being on an island, the tides were the thing.

—William Maier, former Barren Island resident, interviewed in 2012

Being on an island, the tides were the thing.

—William Maier, former Barren Island resident, interviewed in 2012

It was all white sand.…We had these dunes around, and wild roses would grow

around, and of course the water, the tide would come in.…That sand was pretty

hot in the summer, I’ll tell you that much! No trees.

—Josephine Smizaski, former Barren Island resident, interviewed in 2002

around, and of course the water, the tide would come in.…That sand was pretty

hot in the summer, I’ll tell you that much! No trees.

—Josephine Smizaski, former Barren Island resident, interviewed in 2002

The men employed there are negroes, Italians, Poles and other low class foreigners.

—Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 13, 1899

—Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 13, 1899

There was once a place in Brooklyn called Barren Island; it does not exist anymore. It lay in Jamaica Bay, east of Sheepshead Bay and south of Canarsie. A marshy, grassy, sandy land of wind and dunes, the island’s shape and size transformed rapidly as it was buffeted by changing tides and currents. Archaeologists believe it was never heavily settled by the local Canarsie Indians, though they likely used it as a base for hunting, shellfish-gathering and fishing.25 In their turn, European settlers did the same and also grazed cattle and horses in the meadows.26 And as the nearby cities grew, Barren’s combination of proximity and isolation made it a perfect spot for so-called nuisance industries—those smelly, disgusting, but essential activities that city dwellers prefer to keep out of sight. Until then, only a few families lived on the island.

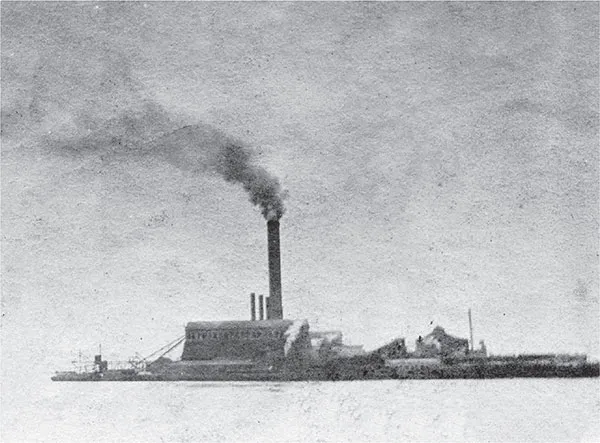

Smoke rising from the chimney of the Barren Island incinerator, circa 1904. Lee A. Rosenzweig collection.

Thus, when the first animal rendering and fish-oil processing plants were established in the 1850s, there was no local population to provide a labor force. African Americans from Virginia and newly arrived European immigrants were recruited to work in the plants. They had to live on the island, as there was no reliable way to commute there. Since they were not displacing anyone and had not come as a homogenous group, these new residents created a community essentially from scratch, combining their existing skills with newly acquired ones in order to satisfy their employers and meet their own everyday needs. Rather than carrying on the traditions of an established society, they made one up as they went along. The location and early history of the island helped to create the conditions that made this happen.

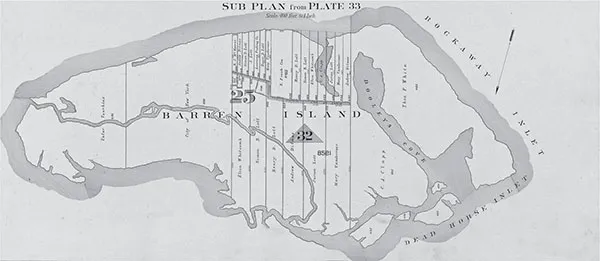

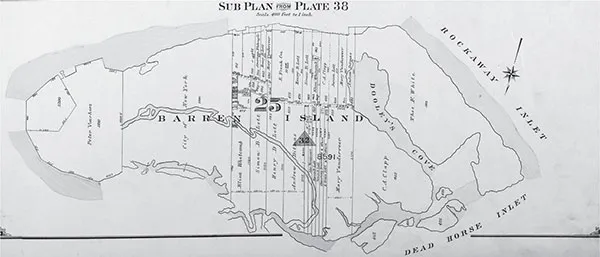

Known to the Canarsies as Equendito, which has been translated as “broken lands,” the island progressed through a series of European names: Beeren Eylant (Dutch for “Bears Island”), Barn and finally Barren Island.27 As the Canarsie name suggests, it certainly was frequently broken by tides, erosion and wind. In its earliest colonial days, according to historian Frederick R. Black, “at low tide only shallow streams separated it from the mainland. Men and livestock could approach it on foot. Small craft had access to its northern shore, and larger vessels could come near its southern edge. These considerations perhaps explain why Barren Island was one of the first of the bay’s islands to be utilized and inhabited by Europeans.”28

These settlers quickly discovered that the island, like other marshy spots in Jamaica Bay, was highly changeable. According to the National Parks Service, which acquired jurisdiction over this area in 1972 when it became Gateway National Recreation Area, at times (as in 1839), Barren Island was connected to Pelican Beach and Plumb Beach to the west, while later storms drastically changed the landscape, once again separating Barren from those landforms by a newly formed inlet.29 Supporting this story of transformation, in 1884, when only a few hundred people lived there, local historian Anson DuBois described Barren as a place of rapid change in recent memory: “Its length lay formerly north and south, but it now extends in greatest length east and west. The area of the island has very considerably decreased within the memory of persons now living.”30

As time went on and the island’s industries and population increased, Barren’s instability became a serious problem. In November 1905, a large building used as a warehouse and dormitory “was sucked out of sight beneath the waters of Jamaica Bay.…It took just thirteen minutes for the bay to swallow the building.”31 The next day, “another large slice of the island disappeared into the bay.”32 Islanders remembered similar past disasters, and everyone seemed to have a theory about why the island’s boundaries were so unreliable: the meeting of multiple currents,33 a “lake of quicksand… beneath the eastern point of the island,”34 tides that were intensified by changes in the nearby Rockaway peninsula.35 Though no one was quite sure exactly why pieces of the island tended to fall off, what everyone agreed on was the likelihood that it could happen again; “many of the inhabitants [were] alarmed lest the entire island sink into the sea.”36

“Double Page Plate No. 34.” Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6e4b3210-0ab4-0132-ff3a-58d385a7b928.

“Brooklyn, Vol. 3, Double Page Plate No. 39; Sub Plan from Plate 38; [Map bounded by Barren Island, Part of Ruffle Bar; Including Duck Point Marshes, Pumpkin Patch Meadows].” Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6c152750-a19e-6b6e-e040-e00a180611af.

Some things stayed the same—like the sand. In the 1700s, “the Town of Flatlands leased Barren Island to William Moore, who mined beach sand from the area.”37 In 1830, the pirate Charles Gibbs buried treasure in the sand (only some of it was reportedly ever recovered), and the island was described as “wholly composed of white sand” by DuBois in his “History of the Town of Flatlands” in 1884.38 Even in 1929, after the island had been attached to Brooklyn proper by landfill and the extension of Flatbush Avenue, a wandering hunter managed to become completely disoriented and fall unconscious during a sandstorm.39

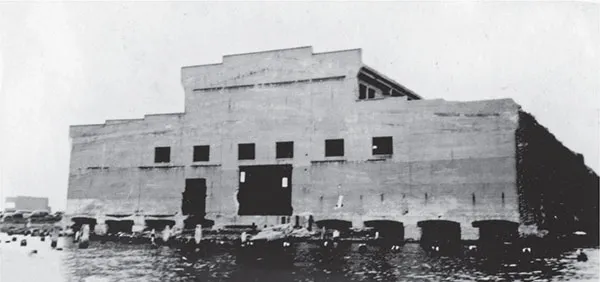

The old “glue factory” at Barren Island, summer of 1937. Factories were often located right on the water, and when the island’s land shifted, they occasionally fell into Jamaica Bay. Lee A. Rosenzweig collection.

But changeability was far more prevalent than consistency. Trees and other forms of vegetation appear to have come and gone. In 1884, DuBois wrote, “Years ago the island was destitute of trees, producing only sedge, affording coarse pasture. Sixty years ago cedar trees sprung up [sic] over the island, furnishing a roosting-place for vast numbers of crows. Few trees now remain.”40 In 1908, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that “there are a few trees in this land in Jamaica Bay, consisting of straggling willows in the parts near the docks and factories, with quite a grove of cedars in the northwest end.”41 In 1921, the New York City Parks Commissioner and Barren Island’s school principal arranged for 150 public school students to take a field trip to Prospect Park. According to the Eagle (which was perhaps exaggerating), these children had “never seen a tree or flower and hardly a blade of grass.”42 Recalling a time not long afterward, William Maier, who lived on Barren Island from his birth in 1917 until 1935, stated in an interview that there was an area that during his childhood “we called the forest…there was a lot of brush and trees. And there was a couple of cedar trees. And I heard tell, years ago, when the island first existed, had cedar trees on the island. But these two cedar trees that were there, were dead.”43 The Cultural Landscape Report identifies these as Atlantic white-cedar and notes that they had been cleared from the island “during colonial times…[because they were] widely used for roof and siding shingles.”44

The same report distinguishes several ecological zones on the island: marine intertidal sand beach, and a maritime dunes community that included both grassland and shrubland. The beach had “no vegetation but [was] abundant with marine life and shorebirds.” Higher up on the dunes, there would have been “grasses and low shrubs, including beach grass, dusty miller, beach heather, bearberry, beach plum, poison ivy, and possibly stunted pitch pines or post oaks. Within the shrubland, species may have included many of those on the dunes, along with eastern red-cedar, Atlantic white-cedar, shining sumac, highbush blueberry, American holly, and shadbush. The grasslands [were] distinguishable from the shrubland by dominance of grasses rather than shrubs.”45 Some of these species, as we have seen, were remembered by later residents. In addition to William Maier’s recollection of cedar trees, he also had fond memories of beach plums: “Oh, I loved those beach plums.…I was eating them before they got ripe. There was a lot of them. ‘Let’s go over and get beach plums!’”

In addition to land vegetation, Maier also remembered the rich animal life that residents took full advantage of to feed their families, or simply for recreation and appreciation of the natural world around them. “We had a place called Dead Horse Bay,” he said. “And my sister and I, at low tide, we went in there, we would [search] for hard-shell clams. We’d walk in maybe an inch or two of mud, but after that was sand. With your bare feet, you can feel the clams. You can reach down and get the clams. My mother could make a real hearty clam [dish]. We could get an awful lot of hard shell clams.” He also remembered distinctive ethnic traditions. “A lot of Italian people used to come down to the beach with their nets. They used to get these shiners [freshwater fish].…They used to pick mushrooms down there, too.” And there were birds and more crustaceans: “We had a lot of wild geese on Barren Island, ducks, and cranes. We called them cranes, a lot of people call them egrets, herons.…A lot of horseshoe crabs. A lot of fiddler crabs. Soft-shell clams. Hard-shell clams.” Not all of these creatures were food for residents, but many were: Maier remembered that Deep Creek was “where we did what I call the snapper fishing,” and of another stream he recalled, “I remember when I was a boy, fishing there for those little killies, bring them home for the cats.”

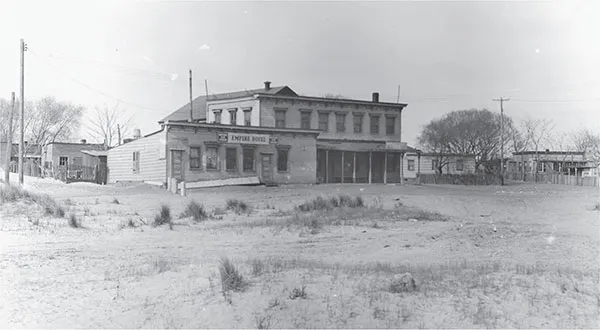

The Empire Hotel on Barren Island, north of Flatbush Avenue and west of Board Road, April 21, 1931. The ubiquitous sparse, grassy landscape is visible here. Photo by Percy Loomis Sperr. Lee A. Rosenzweig collection.

Men fishing on Barren Island, July 5, 1931. Courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Archives, Eugene L. Armbruster Photographs.

Along with the ocean, the shifting topography and the flora and fauna, another aspect of the natural environment that had important effects on Barren Island’s history was the weather. Again and again after its population began to grow in the 1850s, newspapers reported on how ice and fog unpredictably, yet frequently, cut the island off from communication with other nearby communities. In December 1897, for instance, the boat that went to and from Canarsie was delayed for hours by fog several times and even got lost once, causing prisoners to miss court dates in Brooklyn.46 In February 1899, the island was iced in for several weeks. “All navigation above Barren Island is stopped,” the Eagle reported on February 2.47 On February 10, the newspaper stated that the unfortunate “Frank Schowusky, aged 34, driver of a baker’s wagon on Barren Island, was so badly frozen yesterday morning that Dr. Heeve, who was called, has doubts of his recovery.”48 By February 15, the ice was so thick that “one may walk…to Barren Island [from Canarsie or Rockaway] without difficulty.”49 Five years later, in February 1904, the Eagle reported that “all communication with Barren Island and Ruffle Bar [a smaller nearby island in Jamaica Bay] has b...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Early History, Landscape and Population

- 2. Outsiders and Insiders

- 3. Work

- 4. Recreation and Religion

- 5. Municipal Neglect

- 6. Law and Order

- 7. Education

- 8. The End of Barren Island

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author