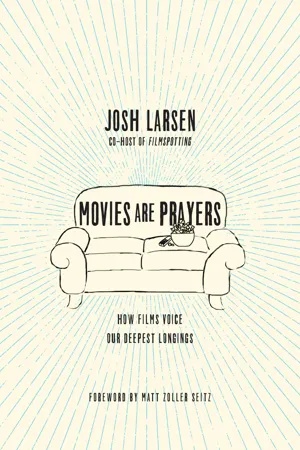

FOREWORD

Matt Zoller Seitz

Whenever I speak to groups about movies or criticism, I am invariably asked which critics I think people should be reading. I suggest a few names, often people who write for major publications or online journals of note. But then I tell them that if they’re interested in form as well as content, and in the relationship between the two—that is, if they’re looking for actual criticism as opposed to reviews, but written in language that can be understood by somebody who didn’t go to film school—then they should be reading critics who write for a religious or spiritual audience.

I suggest this not because I am particularly religious myself—though I do believe there’s more to life than what we can scientifically quantify—but because there’s a disconnect between what marketers have told Christian audiences are Christian films (a narrow slice of mostly bland, ineptly made, and insufferably preachy bits of “product”) and the ones recognized by critics such as Josh Larsen, whose extraordinary book you are about to read. And a critic such as Larsen writes much more perceptively about what a film actually is, what it contains, what it says, and how it says it, than all but a handful of critics who don’t carry the difficult responsibilities that spiritually minded critics shoulder every day of the week.

The committed filmgoer who is also a committed Christian occupies a uniquely precarious position within film culture. Much arts criticism is at best coolly secular or indifferent to faith, and at worst actively hostile to most forms of organized religion, as well as to the notion that the experience of the uncanny or inexplicable or intuitive or mysterious might be applicable to daily life as well as to fictions that involve wizards, witches, Jedi, demons, and prophets.

A critic such as Larsen also encounters resistance (and sometimes hostility) from that sector of the audience that is mainly interested in knowing what sorts of films won’t offend their faith or their sense of propriety, or force them to explain things to their children that they would rather not have to discuss. To this kind of viewer, who thinks of criticism mainly as a consumer guide, criticism of the kind that Larsen practices so well can only provoke discomfort, or the sort of introspection that leads to discomfort, and who wants to feel uncomfortable?

Caught between the proverbial rock and a hard place, Larsen slips free and embarks on his own journey. Like a pilgrim in a novel or poem from long ago, Larsen doesn’t just head directly into the nearest house of worship in the town where he was born and has never left, pick up a prescribed text, and start reciting the old tried and true words, chapter-and-verse. He looks up at the sky and off toward the trees, not just down at the text. He seeks out life experiences he could never imagine on his own and scrutinizes them with an open mind and an attentive ear. He roams. He’s a traveler. A seeker. He is curious and wise, but never self-regarding. He sees faith and finds God in places you might not necessarily expect, and locates lessons—more often questions—in quite a few films that you wouldn’t immediately describe as being concerned with such things.

And Larsen never makes the mistake of assuming that because a film contains subject matter that some might consider objectionable, it cannot possibly be of interest to a viewer who cares about spiritual matters. The stories of sinners often have as much to tell us about the human condition as the stories of saints—usually more, because even on our best days, most of us are closer to sinner than saint: a work in progress, doing the best we can to confront the big issues, but often just kind of muddling through, doing the best we can.

And so you’ll find Do the Right Thing in here, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Avatar, and Rushmore, and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and Top Hat, and A Hard Day’s Night, as well as the filmographies of Hayao Miyazaki and David Lynch, Krzysztof Kieślowski and Martin Scorsese, Terrence Malick and Frank Capra. Larsen writes about love, loss, grief, suffering, and endurance. He writes about ecstasy and abandon, shame and guilt. He finds all of life in movies, even in movies that outwardly seem to have little to do with life as most of us know it, and he connects it back to scripture, to a rich tradition of spiritually inclined literature and visual art, to his own experience, to the history of this country and others, and to faiths besides Christianity. He can read a film as if it were a sacred text or admire it like a cathedral; other times he seems to have moved into it and lived inside it long enough to absorb its sounds and smells and memorize the way the sunlight hits the bedroom floorboards.

The result is an essential book for anyone who thinks of cinema as a place of introspection as well as escapism, and believes that you can find signs and miracles anywhere if you know how to look for them.

--- CHAPTER ONE ---

MOVIES ARE PRAYERS?

Movies can be many things: escapist experiences, historical artifacts, business ventures, and artistic expressions, to name a few. I’d like to suggest that they can also be prayers.

What, exactly, is prayer? You already know. You’ve prayed, even if you haven’t set foot in a church for years (or ever). You’ve longed, you’ve desired, you’ve marveled, you’ve groaned. You’ve looked around at the beauty of the world, as the Welsh miners do in How Green Was My Valley, and said, “Wow.” You’ve seen great suffering, as Sheriff Ed Tom Bell does in No Country for Old Men, and asked, “Why?” Who is it that you and the miners are praising? Why are you and the sheriff bothering to complain?

Prayer is a human instinct, an urge that lies deep within us. Religion came along to nurture, codify, and enrich it. Christians look to the Lord’s Prayer, given by Jesus, as one model for structuring communication with God (Mt 6:9-13). A testimony of praise and an expression of yearning, a confession of sin and a pledge of obedience, the Lord’s Prayer addresses both the nature of God and our desire to be in relationship with him. It is a beautiful encapsulation of our instinctual desire to seek the divine.

Somewhere early in my childhood, I was taught a similar way to structure my prayers: first give thanks and praise, then pray for others, and only after offering confession should I speak of my own concerns. It is a discipline that has served me well, and a method I still follow—although at the end of these busy, midlife days I often succumb to sleep before I make it to confession. (Convenient, right?) Thankfully, there are other structured prayers in my life. Church liturgy, an art form in itself, gives me words from Scripture when I can’t find the right ones on my own. Devotionals encourage a time of patient, quiet, and unhurried contemplation of God’s Word. Requests for prayer on social media—some from friends regarding personal concerns, others in response to global tragedy—jostle me out of the self-involved stupor of my daily routine and remind me to lift others to God.

Often, however, my prayers emerge outside of liturgical tradition, church structure, or prompting by other Christians. The prayers I knew first and still know best are guttural. They’re wonderings and wanderings prompted by those moments, both sublime and sorrowful, that can’t be explained by biological function or natural selection. They’re instinctive recognitions of good (of things worthy of praise) and evil (of things inexplicably bent and broken). Whenever I sense something beyond this temporal world—whether the movement of God or the machinations of wickedness—I respond, without formation or premeditation, in awe, anger, or confusion. In these unplanned and impulsive prayers, I’m just a boy standing before God, asking him everything. (Apologies to Notting Hill’s Julia Roberts.)

Theophan the Recluse, a nineteenth-century bishop in the Russian Orthodox Church, wrote extensively on the role of prayer in the Christian life. In Philokalia: The Eastern Christian Spiritual Texts, Theophan is attributed with this description of prayer: “Prayer is the raising of the mind and heart to God—for praise and thanksgiving and beseeching him for the good things necessary for soul and body.”1 I like this intermingling of the intellectual and emotional elements of prayer, this mixing of the mind and the heart. It recognizes that as much as we try to corral it via rigorous religious tradition (for good and faithful reasons), prayer also takes place beyond the boundary waters, in places and ways we might not expect. This human instinct to reach out in praise or lament or supplication or confession to the divine does not take place only in church, guided by liturgy and pastors. It isn’t limited to early morning devotions, in that serene space before silence gives way to the day. It isn’t strictly the domain of dinner tables, where families gather to recite familiar words (“God is great, God is good . . .”). And it isn’t an instinct shared only by Christians. Prayer can be expressed by anyone and can take place everywhere. Even in movie theaters.

Prayer can be expressed by anyone and can take place everywhere. Even in movie theaters.

Movies as Prayer

Some of my earliest memories are from sitting in church sanctuaries—hearing Scripture read aloud, having a grandmother tickle my arm, feeling the rumble of the organ, straining against an itchy shirt collar. Other memories, from nearly as far back, are from sitting in movie theaters (more comfortable collars, less Scripture). I spent many childhood Saturdays with my movie-fan parents at the theater, while the occasional Sunday found me tagging along with my dad to the church where he was serving as the guest preacher. Perhaps it was inevitable that films and faith would become intertwined in my head and my professional practice. As an adult I eventually found myself, on occasion, at worship on a Sunday morning and in study of a film that afternoon, a transition that felt natural and good. In time, I began to recognize that the very things we had been expressing in prayer as a faith community were also, in a less liturgical way, being expressed on the screen. Prayer was everywhere.

Among the countless anonymous spiritual phrases floating around the Internet is this one (often attributed to a man named Edwin Keith, but hard to pin down to a single source): “Prayer is exhaling the spirit of man and inhaling the spirit of God.” This book examines the ways movies exhale. Not only Chariots of Fire or Amazing Grace. I mean movies you wouldn’t immediately associate with religious meaning. Chinatown. Do the Right Thing. The Searchers. Pinocchio. A Hard Day’s Night. The Muppets. (Yes, the ones wearing felt.)

When Spike Lee exhales, we get Do the Right Thing. When Roman Polanski and Robert Towne and Jack Nicholson exhale together, we get Chinatown. When the Beatles exhale and Richard Lester is there to capture it, we get A Hard Day’s Night. Each of these films, in their own distinct way, offers a response to the two great existential questions that we ask of God almost every day: What do I make of this place? Why am I here? Chinatown answers with a lament. A Hard Day’s Night rejoices. Do the Right Thing seethes, then unexpectedly reaches for reconciliation. Each offers a prayer.

Of course, none of these movies open with the phrase “Dear God.” A fundamental assumption of this book is that prayer can be an unconscious act, one guided by the Holy Spirit as much as our own script (Rom 8:26). For Christians, such impulsive, mysterious prayer is another part of our tradition, one rooted in and directed at the saving God we believe in. We offer quiet, instinctive prayers every day—hopes, worries, and frustrations that never quite take the shape of spoken words or fit into religious routines. Yet those who would not claim Christian identity also make such deeply felt gestures. And we all direct these gestures at an assumed audience outside of ourselves. God may not be the name always given to that unseen listener, but he is nevertheless the one who hears.

In Prayer: Finding the Heart’s True Home, Richard Foster describes the malleability of prayer: “Countless people, you see, pray far more than they know. Often they have such a ‘stained-glass’ image of prayer that they fail to recognize what they are experiencing as prayer.”2 Movies offer these sorts of unconscious prayerful gestures, only much louder and on a giant screen. If it helps, imagine stained-glass windows along the walls of a theater. It’s no coincidence, after all, that the spaces have similar architecture. The knee-jerk comparison to make is a pejorative one: that both places are designed for worship, the implication being that good people go to church to worship God and bad people go to the movies to worship everything else. There is some truth to this reductive reasoning; certainly the most shallow and exploitative of our movies can direct our desires in self-destructive ways. But I think a more fundamental commonality between sanctuaries and theaters is the notion of focus. In both instances, we’ve set aside our time and our space to gather in community...