![]()

The Book of

MICAH

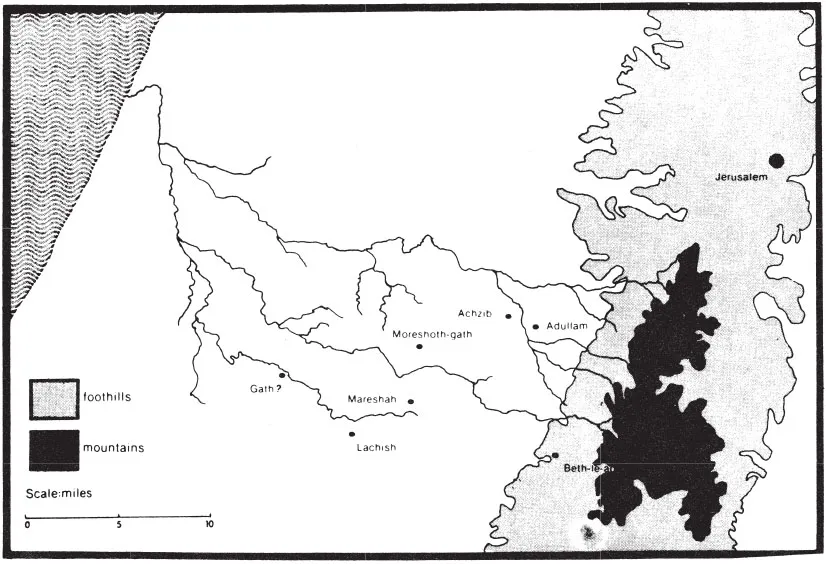

(The Southern Shephelah. See pp. 279–280.)

INTRODUCTION

1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO MICAH’S MINISTRY

The heading to the book assigns the prophet’s ministry to the reigns of Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah. For the reader who has a basic knowledge of the history of Israel and Judah, this reference to the second half of the eighth century B.C. speaks volumes. By collating references to the period in the religious histories of Kings and Chronicles and in the Assyrian records, and by comparing social allusions in both Isaiah and Micah, a good deal of the social and political history of the period can be reconstructed. Micah’s oracles, therefore, may be considered in the light of their environmental context.

The heyday of Uzziah (767–739 B.C.) was over. In his reign the imperialistic thrust of Assyria westward and southward had been temporarily halted by internal dissension, but not before the powerful Aramean state of Damascus to Israel’s north had been crippled. Benefitting from the lull and the economic opportunities it presented, Jeroboam II of the Northern Kingdom, and in alliance with him his contemporary Uzziah of Judah, had surged forward and won territorial and commercial gains. Uzziah’s death marked the end of an era, as decisively as did Queen Victoria’s. The old world was no more, though for a time men basked in the last rays of its lingering light.

The reign of Jotham, Uzziah’s successor, coincided with fresh Assyrian campaigning under the vigorous Tiglath-pileser III, Assyria’s Napoleon. Damascus and Israel, by now tributary to Assyria, chafed under their vassalage and together put pressure on Ahaz, the young crown prince of Judah who had just succeeded Jotham as king, to support their rebellion. Ahaz’s appeal to their overlord certainly relieved that pressure, but at the cost of enmeshing Judah itself in the Assyrian net. First Damascus and then Israel were removed from the political scene, paying the ultimate price for their continued lack of cooperation with Assyria. Samaria, Israel’s capital, fell to Assyrian besiegers in 722 B.C., and deportation of the people of the Northern Kingdom, begun some ten years before, was rigorously resumed. Undeterred by this demonstration of the iron fist of his suzerain, Hezekiah later attempted to secede from the empire, heading an anti-Assyrian coalition of Palestinian and Syrian subject states. Judah might have suffered the fate of its northern neighbor, but although in reprisal the country was overrun by Assyrian troops in 701 B.C., Jerusalem itself was not taken, and Hezekiah was let off with payment of a fine and loss of part of his territory to the Philistines.

Micah lived in a period of economic revolution, which was proving a mixed blessing. Unfortunately the influx of material prosperity had spawned a selfish materialism, a complacent approach to religion as a means of achieving human desires, and the disintegration of personal and social values. Wealth was invested in land, with the result that the traditional system of agricultural small holdings collapsed with the growth of vast estates, and material and emotional distress ensued. Age-old sanctions associated with the divine covenant were shrugged off, and social concern was at the bottom of the list of priorities of national and local government officials. Even religious leaders—priests and prophets—did little more than echo the spirit of the period, buttressing the society that gave them their livelihood.

Micah’s role was to act as religious commentator in Jerusalem on the contemporary social scene. As a prophet, one of God’s men in Judah, he spoke as a representative of the divine will. It fell to him to deliver Yahweh’s stern warning. As a countryman from the fertile lowlands of southwest Judah, doubtless he had firsthand knowledge of the sufferings of the rural proletariat and was thus providentially prepared to voice God’s own indignation. This Amos of the Southern Kingdom realized that the God of the nation could not lightly be brushed aside. Though hailed as the great standby of his people, he would in fact intervene in terrible judgment, and only after they had been diminished and refined in the crucible of divine chastisement would he rescue and rehabilitate.

Addressing himself to the nominal theocracy of Judah, the prophet attacked the establishment for abandoning divinely ordained standards in favor of self-interest, to the point of neglecting or actively illtreating the underprivileged. He saw Judah to be on the brink of disaster, whose causes he interpreted in typical prophetic fashion not as solely political but as theological at heart. Claiming God-given insight, he discerned a close link between the social and economic abuses of the Judean lawcourts and general civil administration on the one hand, and the irresistible, glacier-like menace of Assyria on the other.

Jer. 26:18f. records a fascinating tradition of the stirring effect the bluntness of Micah’s fatal diagnosis and prognosis had upon King Hezekiah and his subjects. It is probably not going too far to say with A. F. Kirkpatrick that “Hezekiah’s reformation was due to the preaching of Micah.” In fact Judah staggered on after the 701 B.C. crisis for another century or so before God’s dire threats through Micah materialized in all their starkness. After 587 B.C., when Jerusalem fell and the Judeans were deported to Babylon, men must have looked with new eyes at Micah’s reasoned oracles of doom, bordered by hope on the farther side.

In OT study Micah has tended to be overshadowed by Amos and Hosea and especially by his great contemporary Isaiah, whose prophetic material has been preserved in much greater quantity. Stylistically, to be sure, he sometimes has more of the qualities of an orator than of a poet. But his message is proclaimed with no uncertain sound, as with passionate forthrightness he attacks the social evils of his day. His stubborn refusal to float on the tide of his social environment, and his courageous stand for his convictions of God’s truth, must commend Micah to believers in every age.

2. DATING, AUTHORSHIP, AND COMPOSITION

The heading in 1:1 attributes the prophetic ministry of Micah to the period of the second half of the eighth century B.C. An external indication of date occurs in Jer. 26:18f., where 3:12 is assigned to Hezekiah’s reign. Apart from these explicit chronological pointers, the historical circumstances of each prophetic oracle can be constructed only from internal evidence. The authenticity of each oracle is bound up with its applicability to, and reflection of, its historical setting. Over the past century, scholars have been prone to assign to periods after Micah’s lifetime the following oracles: 2:12, 13, all or some of those in 4:1–5:9, and 7:8–20. Do we in fact have in the book of Micah an amalgam of oracles, i.e., Micah’s own supplemented with later ones? The answer must lie in an investigation of the contents of the material from a chronological viewpoint.

The oracles of chs. 1–3 are almost universally assigned to Micah apart from 2:12, 13. The first unit is 1:2–9. The fall of Samaria evidently lay in the future, to judge from vv. 6, 7. Accordingly this message was given before the city fell to Sargon II in 722 B.C. after a three-year siege, which represented a death-blow to the Northern Kingdom. Was it as early as the Syro-Ephraimite War of 734 B.C., after Damascus and Israel, rebelling against their Assyrian overlord, unsuccessfully urged first Jotham and then Ahaz to join in a western uprising? It was in that period that Isaiah predicted that an Assyrian flood would not only overwhelm the two northern states but would also “sweep on into Judah, it will overflow and pass on” (Isa. 8:6–8). There is a striking similarity to vv. 5 and 9 here, where the overthrow of Samaria is made a warning to Jerusalem to prepare for a like fate. Micah’s concentration on Samaria do...