![]()

1

A Tale of Two Missions

The Western Hemisphere in the late eighteenth century was convulsing. A slave revolt in Haiti plunged that French colony into civil war, the Austrian and Ottoman Empires were embroiled in war, France was in turmoil, and the colonies in America were asserting their independence. Revolutions reverberated around the Occident from Belgium on down through Latin America in the decades of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, radically changing the geopolitical landscape. The industrial revolution fed the rise of capitalism as a major world force, which shattered the boulders of wealth primarily held by families who governed the world, and sent pieces of mammon flying out into corporations—a relatively new entity on the landscape, different from individuals or from states. This new body comprised mostly men who knew how to take raw materials like cotton or iron, combine it with working class or slave labor, and turn a profit for themselves and their investors.

The birth of the modern American Protestant missionary society emerged out of the context of these convulsions and was indelibly marked by the political and economic landscape onto which it emerged.

Most early Protestant missionaries, both American and European, were immersed in the spirit of capitalism taking root in the West. The leaders that gave shape to American mission societies in the nineteenth century were business-minded men. Families like the Rockefellers, Carnegies, Vanderbilts and the Morgans invested heavily in their Protestant churches and in domestic and foreign missions. These wealthy philanthropists were builders of the great educational institutions out of which most Protestant missionaries came, and promoted a positive attitude toward the corporate worldview within American Protestantism.

Adoniram Judson attended what would become Brown University and graduated valedictorian in 1807. He joined a handful of other collegians at that time and forged a secret missionary society—the Society of the Brethren—with the intention of bringing the gospel to foreign lands. Judson was joined by Samuel Nott of Union College, Samuel Newell of Harvard, and Gordon Hall and Luther Rice of Williams College. A couple of key clergymen who supported the boys’ desire to become missionaries determined that “if a foreign mission were to be anything but a pious hope, a foreign missionary organization had to be formed to popularize the idea, raise money, disburse it, select missionaries, assign them to stations, support them and supervise their activities.”1

This was, after all, the way successful people got things done. At that time it was axiomatic that if someone had a passion to advance anything in foreign lands, even Christian mission, a corporation needed to be formed, complete with investors, boards of directors, executive officers, employees, recruiters and accountants. The result was a missionary corporation, a Christian version of the for-profit trading company. The eighteenth-century North American and European imagination had become enchanted by the lords of profit.

The eighteenth-century North American and European imagination had become enchanted by the lords of profit.

These well-educated young men seeking to be foreign missionaries presented themselves to the annual General Association of Congregational Churches on a New England afternoon full in bloom with foxgloves, geraniums and Canterbury bells in June 1810. Protestants had already been debating the rightness of sending foreign missionaries at all. “If God wants to save the heathen,” one Baptist pastor told the “father” of modern missions, William Carey, “he will do it without your help or mine!” That debate was beginning to be won by missionary advocates across Europe, and the Congregationalists in America were now coming on board with that conviction. But these young men could not simply be released and commissioned to pursue their passion without any structure. And the primary organizational construct these Congregational leaders were skilled at building was commercial businesses, so the sending structure was designed and referred to as a corporation.

Dr. Manasseh Cutler was the moderator of the assembly and an astute businessman. He and a dozen others “bought” the state of Ohio, displacing thousands of Native Americans. He knew how to build a corporation. This new Christian Missionary corporation would be called the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Mission (ABCFM). The first two treasurers, Samuel Walley and Jeremiah Evarts, have been described as “shrewd Yankee Christian businessmen.”2 “If we are to be the instruments of doing anything worth mention for the church of God and the poor heathen,” Evarts was heard to have said, “we must exhibit some of that enterprise which is observable in the conduct of worldly men.”3 The creation of the first formal American missions association was forged with all the business savvy that the “worldly men” of the early nineteenth century could muster.

To send these young men (most would procure wives, some just days before the journey) would require raising $6,000, or roughly $168,000 in today’s dollars. The chief precedent for raising this kind of money was commercial investment for profit. Investors were slow to put their money behind this effort. Returns on their funds would be spiritual, not material, and a venture of this sort came with a good deal of risk. The society sent Judson to London to discover what he could from the London Missionary Society, which had already been in operation as a missionary corporation for fifteen years. Perhaps they would even be willing to fund the mission.

The society in London, however, was already preparing to spend £10,000 on their missionaries that year (£321,700 by today’s reckoning, or nearly $500,000). They were not terribly interested in taking on the financial burden of a team of American missionaries, at least not without the English board of directors exercising governing control over the American mission. This was something the American board was loath to consider. After all, Americans had just freed themselves from the bondage of British control and were not about to put themselves under the yoke of a British missionary society. Still, the ABCFM wouldn’t mind taking British funds for an American mission. You could say that the Americans wanted the “taxation” of the London Missionary Society without their representation.

The mission party finally shipped out to Asia in February 1812, just when United States declared war on Great Britain. As if war were not enough of a challenge, three employees of the American mission bailed out of the missionary corporation before even reaching Burma. Adoniram, his wife Ann, and Luther Rice had come under the conviction that the Congregationalists were wrong on the issue of baptism. So a new missionary corporation was erected to employ them, the General Missionary Convention of the Baptist Denomination.

Like the commercial pattern from which it was cut, the American missionary corporation was desperately dependent on the financial resources of external investors for success. A less corporatized alternative would have been to help the young missionaries obtain passage overseas via professional means or through immigration. Maybe, like the apostle Paul, a mixture of financial contributions and paid employment would have sufficed. Structurally, the investors wanted substantial control over the mission, refusing funds from the London Missionary Society for fear that this corporate entity would take over the American corporate mission. Finally, rather than allowing some freedom for the missionaries to determine policy, a denominational issue, much like a corporate policy, ended the employment contract. The Christian-Industrial Complex was under way.

The Leile Mission

An African proverb says, “Until lions write their own history, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” For centuries the story of the first American missionaries were written by and written about the white, Ivy League collegians in New England. Adoniram and Ann Judson have often been lauded as the first missionaries from the United States, and their place in history uncontested. Then in the 1960s Stetson University history professor E. A. Holmes wrote a shocking article for the Baptist Quarterly displacing that myth. It was the story of a freed black slave who went as a missionary to serve among slaves in Jamaica.

“Until lions write their own history, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

African proverb

The thirty years between the end of the war for American independence and the start of the War of 1812 mark a grand exodus. British loyalists, black slaves and Native Americans hemorrhaged out of the country on retreating war ships.4 Some fled to St. Augustine, Florida, others to Nova Scotia and some to London. Thousands immigrated to nearby Jamaica. These three decades also separate two radically different paradigms for American Protestant mission. In the efforts of these freed slaves an older and lighter missionary structure emerged. They were no less intentional or effective in establishing outposts of God’s kingdom abroad than the collegians who departed thirty years later, but they were not the engine to which Protestants, by and large, chose to hitch their train.

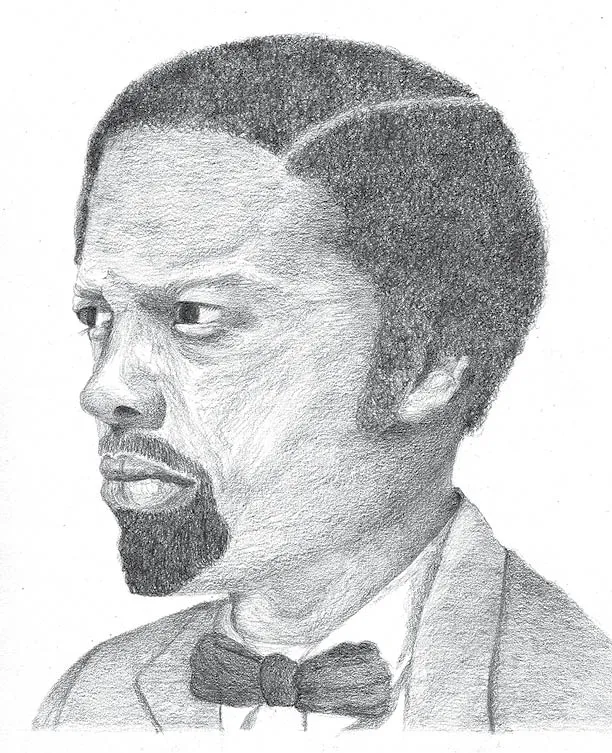

One former slave swept up in the British exodus was a gifted preacher. George Leile’s Loyalist master, Henry Sharp, had given him his freedom before the start of the Revolutionary War, and Leile was ordained to preach to slaves in South Carolina and Georgia. Leile won to faith the early patriarchs of black American Christianity. These were men who established some of the first black congregations in the United States, men like David George and Andrew Bryan. Bryan was one of only three black Baptist preachers to remain behind in Savannah, Georgia, as the British retreated along with blacks who feared reenslavement. In staying, Bryan faced harassment, beatings and imprisonment at the hands of whites who detested him for having the sheer audacity of gathering blacks for worship.5 Under the protection of the Union Jack, David George, along with nearly thirty-five hundred asylum-seeking slaves, fled the United States to Nova Scotia and later immigrated to Sierra Leone, where he led congregations of blacks fleeing the United States.

George Leile, first American missionary. Pencil drawing by Janine Bessenecker.

George Leile and his wife, Hannah, however, had their sights set on Jamaica. Events surrounding the Leiles could hardly be more differe...