![]()

Part One

Background

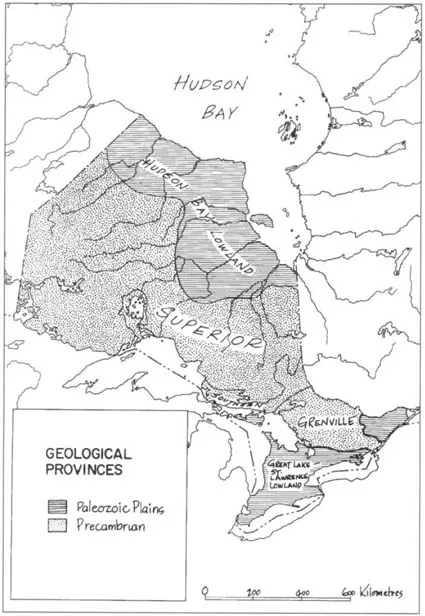

Map 1.1

Geological Provinces of Ontario

![]()

1 The Ontario Landscape, circa A.D. 1600

WILLIAM G. DEAN

Today there is no place where one can feel confident the landscape remains exactly as the first inhabitants saw it. No matter how remote, the most isolated places have not escaped being altered by people in some subtle way. Even without human interference, the landscape itself is never completely stable. Natural processes continually change existing vegetation, landforms, stream systems, soils, and animal life – in short the total ecosystem. Climatic variations, natural fires, and erosion are but three crucial elements among many involved in the alteration of the landscape; over the centuries such elements have affected in many ways, still little understood, the way of life of the Amerindians.

The landscape of Ontario circa A.D. 1600, that is, before the arrival of Europeans, was occupied by an indigenous population. Scattered and often living in isolated groups, the Amerindians made use of their environment and thus changed it. Those who lived in semi-permanent settlements cultivated maize and other crops in cleared areas of the forest that enclosed their villages; locally, therefore, they changed their surroundings. Indeed, an early French missionary, Gabriel Sagard, described Huronia, in present-day northern Simcoe County, as “a well cleared country bearing much excellent hay.”1 Others subsisted by hunting and trading up and down the river systems, and in all likelihood, except for causing the occasional forest fire, set intentionally or accidentally, they scarcely altered the primeval wilderness that was their home.

Major Geographical Units

To gain some insight into the Ontario landscape at the beginning of the seventeenth century, one must turn to reports of explorers or travellers. Although they made no apparently conscious effort to do so, the earliest accounts of the land and resources distinguished the major geographical units within Ontario. Early in the seventeenth century, for example, Champlain referred to the “pleasing character” of the land south of Georgian Bay and the “ill favoured” “bad country” to the north.2 Captain Thomas James, in 1633, wrote of the bleak coasts of Hudson and James bays, “utterly barren of all goodness.”3 In 1822 the shrewd and imaginative Robert Gourlay prepared a map consisting of three areas: the peninsula between Lakes Huron, Erie, and Ontario and the Canadian Shield; the Canadian Shield; and the Hudson Bay Lowland. These are still recognized as the fundamental landscape regions of Ontario (see Map 1.1, page 2). The Amerindians who inhabited this vast area made their own accommodations to each region.

Territorially, Ontario encompasses over a million square kilometres, of which nearly 180 000 square kilometres are inland waters. This is roughly one-tenth (10.8 percent) of the total size of Canada. The south-north distance by air from Middle Island in Lake Erie, the most southerly place in Canada, to Fort Severn on the shores of Hudson Bay is over 1 770 kilometres. From the southeastern limit near Cornwall to the northwestern just beyond Kenora, the air distance is over 1 609 kilometres.

Despite the geographical immensity of Ontario, the physical variation in a general sense is relatively small. The comparative uniformity is reflected in the relatively small and gradual differences in elevation. Most of Ontario stands between 152 metres and 304 metres above sea level. Only along the shores of James and Hudson bays is sea level reached. Ogaidaki Mountain, Ontario’s highest point, reaches 665 metres. This vast extent of country with so few impediments to mobility allowed the Indians, if they so desired, to travel long distances with comparative ease.

The physical characteristics of Ontario are most conveniently described in the context of Robert Gourlay’s three broad regions: the Canadian Shield, the Southern Ontario Plains, and the Hudson Bay Lowland.

The Canadian Shield, exposed over much of Northern Ontario, has been for centuries the home of Algonquian-speaking Indians – hunters and fishers par excellence. It is a land of many lakes tied together by a network of streams and rivers that provided highways for the Native peoples both summer and winter. Thin acidic soils and short cool summers inhibited the raising of crops. Accordingly, the Amerindian inhabitants had little choice but to be hunters, fishers, and gatherers.

Across the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowland, two steep escarpments of more resistant rocks rise sharply above intervening lowlands underlain by weaker rocks (see Map 1.2). Their steep limestone cliffs face the Shield; their backslopes dip gently to the southwest. Here on this lowland the horticultural Iroquoians made their home. Soil and climate, favourable for the raising of crops, allowed them to lead a sedentary existence.

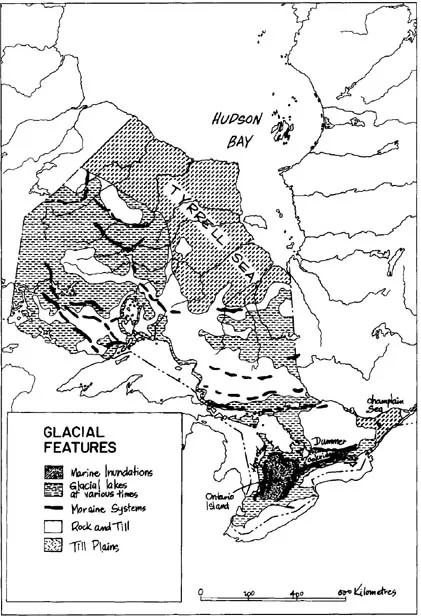

Map 1.2

Glacial Features of Ontario

The other plain, the Hudson Bay Lowlands of Northern Ontario, is completely different. Its surface is comprised largely of the floor deposits of the Tyrrell Sea, the early post-glacial forerunner of Hudson Bay. As the land rebounded from the weight of the ice sheet, this sea gradually fell in level to the present configuration of Hudson and James bays, forming flights of raised beaches, bars, and spits whose low profiles are the only relief on an otherwise flat plain of over 260 000 kilometres. Across the plain the major rivers flow in canal-like valleys; the only significant tree growth is found along these river banks. Muskeg and bog cover most of the plain, and the dominant sphagnum moss forms a kind of organic terrain, controlling local drainage and vegetation patterns.4 Within these lowlands only a few Algonquians eked out a meagre existence.

Retreat of the Glaciers

The massive glaciers of the last two million years of Earth’s history – the Pleistocene Ice Ages – had profound effects on the Ontario landscape, especially the last, “Wisconsinan” ice advance. This reached its maximum limits well south of Ontario approximately 18 000 years ago. It wasted away from the Great Lakes area beginning about 14 000 years ago and disappeared from Northern Ontario between 8 000 and 9 000 years ago. The Wisconsinan ice sculptured the details of the Ontario landscape and produced the network of waterways and the gentle terrain that later became the home of the Iroquoians and Algonquians.

Of particular significance both to the appearance and human settlement of Ontario were the landforms resulting from the rise and fall of the Great Lakes. As the Wisconsinan ice sheet melted, large and small melt-water lakes gradually evolved into the modern Great Lakes over a period of some 13 000 years. Various recognizably independent lakes successively occupied each of the present lake basins.5 Between 13 000 and 11 000 years ago, Lake Whittlesey and then Lake Warren filled the Erie Basin, Lake Iroquois the Ontario Basin, and Lake Algonquin the Huron–Georgian Bay basins. At their highest levels, all extended many kilometres inland from present lake shores. In turn, all gave rise to a lake-bevelled terrain, often clay floored, bordered by discontinuous, usually sandy shore structures. Along the beaches left by these bodies of water, evidence of early humans has been recovered. Other large pre-glacial lakes later in time profoundly affected the landscape of Northern Ontario. Successive high- and low-level stages of Lakes Barlow, Ojibway, and Antevs in northeastern Ontario produced the extensive clay belts of the area.6 A similar succession of fluctuating lake levels occurred in northwestern Ontario where Lake Agassiz flooded eastwards from central Manitoba, virtually to Lake Nipigon during some phases.7 Similarly, when some 11 500 years ago the Champlain Sea flooded the St. Lawrence Lowlands, salt water from the Tyrrell Sea inundated the Hudson Bay Lowland.8 Not until the water receded and the flora and fauna had become re-established were the Aboriginal peoples able to occupy these areas. With the draining of the great glacial lakes, Ontario came to look very much as it does in thickly forested places today.

Ontario’s Climate

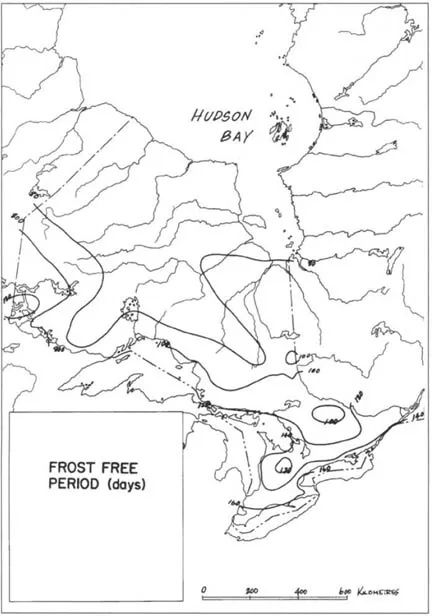

Most of Ontario’s territory is truly northern, yet its southernmost peninsula juts as far south as the latitude of Florence in Italy and the northern boundary of California in the United States. Thus, climatically, this land ranges from an Arctic climate along the shores of Hudson Bay to the climate of temperate southern regions along the shores of Lakes Erie and Ontario. (See Map 1.3, page 8.)

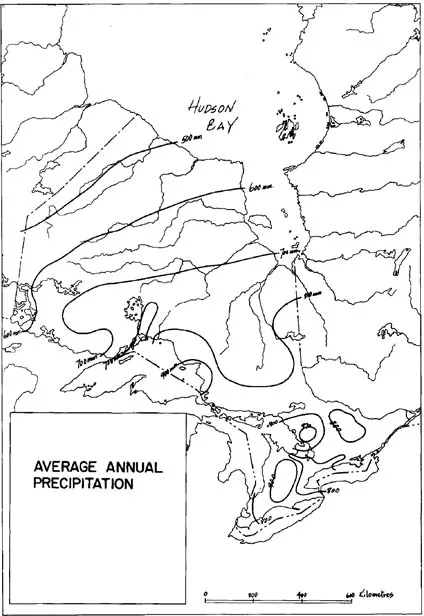

The Great Lakes moderate to some degree Ontario’s climate of extremes. They retard the warming of the surrounding land in spring and early summer because the water remains cool. They also extend the autumn season by retaining their summer warmth. In all seasons, the lakes are an important source of moisture, providing much of Southern Ontario with unusually uniform precipitation throughout the year. (See Map 1.4, page 9.) Because of these favourable climatic conditions, the Native peoples of the southern parts could engage in horticulture.

The coolest climatic period in the historic era is known as the “Little Ice Age.” Authorities differ on its precise dates, but there is no doubt its major effects were felt between A.D. 1430 and A.D. 1850. Except for a brief warm spell between 1635 and 1650, the whole period between 1600 and 1730 was one of severe cold. The nadir of post-glacial low temperatures was reached between 1665 and 1685.9 Much warmer weather has been experienced in the twentieth century.

Although there were undoubtedly episodes of equable weather, the overall climate of the 1600s was certainly harsher than it is today. Average temperatures ranged from one to three degrees Fahrenheit lower, which meant slightly shorter, cooler summers. Precipitation, too, was different. Droughts, for instance, have been calculated as having occurred two to three times every ten years, some severe enough to produce crop failures and famine among the Huron.10 Midsummer frosts were then not uncommon. In 1600 ninety-day frost-free periods were probable, still a long enough growing period for most of the crops cultivated by Native peoples. It was, however, only in Southern Ontario that climate11 and soils amenable to their agriculture existed. The northern or Boreal climates and soils were unsuited to agriculture.

Map 1.3

Frost-Free Period (Days) in Ontario

Map 1.4

Average Annual Precipitation in Ontario

Boreal climates are harshly cold, having mean annual temperatures at or below freezing. Ontario’s tiny fragment of the Arctic extends in a narrow band along the south shore of Hudson Bay and northwestern James Bay, a treeless, open tundra. This frigid band of land was likely not inhabited by Amerindians until the arrival of European traders.

Vegetation

Before it was stripped and forever altered by European farmers, lumbermen, and others, most of Ontario’s vegetation consisted of relatively dense forest interspersed with open park-like woodland. Today, Ontario includes the remnants of what were once three major distinctive forest regions: the Southern Broadleaf Forest, the Southeastern Mixed Forest, and the Boreal Forest.12 (See Map 1.5.) The Native peoples accommodated their lifestyle to their local environments.

Southern Broadleaf Forest

Extending inland varying distances from the shores of Lakes Huron, Erie, and Ontario, from Goderich to Belleville, the Southern Broadleaf Forest is a continuation of the widespread deciduous forests of the eastern United States. It probably reaches this particular northern limit because of the moderating influences of Lakes Erie and Ontario. In composition it has many similarities with the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Forest in that prevalent trees are sugar and red maple, beech, black cherry, ironwood, basswood, white ash, and red and white oak. Also present are white elm, shagbark, hickory, and butternut. Within various combinations of these, however, are scattered other broad-leaved trees such as the tulip tree, paw-paw, Kentucky coffee-tree, wild crab, flowering dogwood, chestnut, black gum sassafras, hickory, and black and pin oak, which reach their northern limits here. In addition, black walnut, sycamore and swamp white oak are mainly confined to this region. Vast open oak woodlands, in some places containing prairie grasses, formerly covered the extensive sand plains of the region. Conifers are comparatively few, being represented only by white pine, tamarack, white and red cedar, red juniper, and hemlock.13 There are also many southern species of shrubs and herbs. The Indians used many of these tre...