![]()

PART ONE

Life on the Margins: Cultivating Community

![]()

1

WATERLOO COUNTY IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Those in power write the history, while those who suffer write the songs.

— Frank Harte

A SEARCH FOR LAND

As the numbers of European settlers and their U.S.-based descendants increased in Lower Canada (modern-day Ontario) during the eighteenth century, the Indigenous Peoples of the province found themselves competing for natural resources and land in what had once been their traditional hunting and seasonal settlement territories. To control and potentially mitigate conflict with the colonists, King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763. In its simplest sense, the Proclamation was designed to effectively define the Crown’s jurisdictional boundaries and accordingly reinforce its governance of its conquered land. This was not intended to permanently settle the issue, and yet the act stirred controversy — many of the settlers balked at the idea of sharing land with the Indigenous Peoples of the region. They were worried that they were now at risk of losing the land that had been granted to them by the Crown, because of the newly established territorial boundaries.3

Even modern historians disagree as to whether this legislation was detrimental or beneficial to later Indigenous land claims, suggesting that the British Crown was making a show of assuaging Indigenous concerns over the perceived encroachment of white settlers while at the same time increasing their own political control over the territory. This arguably lessened the Indigenous claims for land ownership in favour of the white settlers.4, 5 Other historians believe that this Proclamation effectively recognized Indigenous Peoples’ rights to claim the land that they occupied in a way that previous legislation had not considered, irrespective of the land claims of the white settlers.6 The truth is that the boundary claims were anything but permanent. This lack of a solid resolution was ignored for the time being, however, since, within a few years, the British Crown had other concerns as it prepared for war with its American colonies. It now turned to the Indigenous Peoples for help.

JOSEPH BRANT AND THE LAND FOR THE SIX NATIONS RESERVE (1743–1807)

Joseph Brant, an influential Mohawk military leader, was not a full-blood Mohawk; however, he enjoyed life as a man who benefited from and existed between two worlds — both Indigenous and white — on reserve land. Many today recognize Brant’s iconic Indigenous significance, both positive and negative, to the Six Nations Confederacy7 — regardless of his ancestry or interethnic political associations.

He travelled to London, England, in 1775 to solicit support for his people in view of the pending war between the American States and the British Crown.8 Although not a hereditary chief, Brant, as a result of his military office, had the prestige and status to be a powerful advocate for his people. In his role as military leader and translator, Brant seized upon an unprecedented opportunity that would have far-reaching historical effects. The deal Brant struck specified that if the Iroquois (also known as the Haudenosaunee and the Six Nations Confederacy) fought in support of the British, the Crown would confer a land grant to them in Canada (or, as it was known then, the territory of British North America).9 By 1783 Brant had selected the Grand River valley as the place where he and his people would like to settle. On October 25, 1784 (and at the direction of the Crown), Sir Frederick Haldimand issued the Haldimand Proclamation, effectively granting ownership to the Six Nations Confederacy, in deference to their military support for the British interests in the Revolutionary War, the land running six miles (ten kilometres) on either side of the Grand River valley along its length.10 It should be noted, however, that Brant was not above reproach for his territorial gains from the Crown. In fact, he encouraged Loyalist friends of his from Butler’s Reserve (with whom he had fought in the Revolutionary War) to settle with their families on the same reserve land, offering some of them larger land claims than those afforded to some other Six Nations settlers.11 In 1798 Brant built himself a large two-storey home in the growing nearby settlement that took his name — Brantford. For the purposes of the later histories contained within this book, we are most concerned with Blocks 1, 2, and 3 of this tract.12 That there were (and still are) ongoing disputes and misunderstandings concerning the divergent interests over this tract of land is a story well-documented and seeking resolution.

Suffice it to say, by the end of the eighteenth century, a growing group of Pennsylvania German farmers were looking for cheap land and Chief Joseph Brant believed he had the right to sell some of the land his people had acquired from the British Crown — 94,012 acres13 and in May 1796, first evidence of this transaction between Brant, Philip Steadman Jr., Richard Beasley, and William Wallace (the attorney for Joseph Brant) was registered for the sale of Blocks 1, 2, and 3, accordingly.

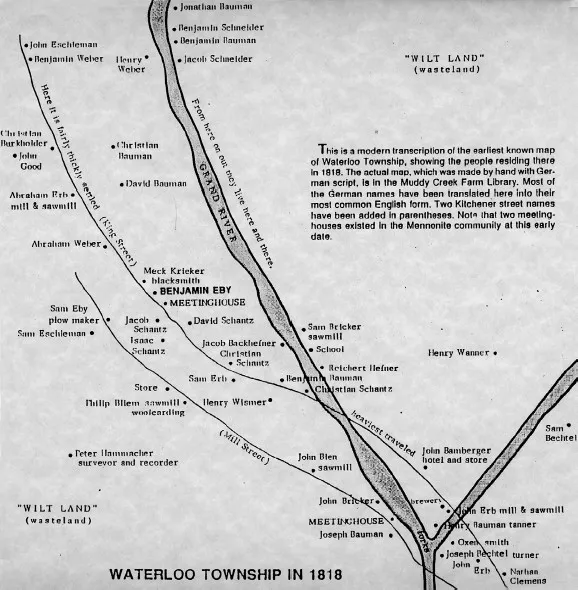

The land that became Waterloo County was, for the most part, a heavily forested and lush region made up of old-growth trees and fertile soil. Indigenous people had selectively cleared some areas in the region, leaving pockets of open grassy areas where they established seasonal subsistence gardens and village settlements, and engaged in successful hunting and fishing. The Mississauga14 had also established strategic pathways that enabled them to move from one camp to another — many of which eventually were co-opted to become some of the area’s oldest roads. Mill Street in Kitchener, which ran beside what became known as Schneider Creek, is one such former trail.

PENNSYLVANIA COMES TO WATERLOO

Most of the early white settlers to this area were, as previously stated, Mennonite farmers — the descendants of Anabaptists who had settled in the Pennsylvania area nearly a century before. Having already established successful farming communities in Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania Germans found that land had become increasingly scarce and more expensive as the eighteenth century progressed. By 1784 some of the frugal Mennonites who searched for cheaper land to purchase began to emigrate to the Canadian side of the Niagara Region, settling in Lincoln County, Ontario (in and around Vineland). What they found was lush land with fertile soil, and in time the community they built flourished and became known colloquially as “the Twenty,” as it was established along the nearby Twenty Mile Creek, so-named because of the location of its mouth, which is twenty miles west of the Niagara River.

Word of their success spread to their friends and neighbours back home in Pennsylvania. Some of these countrymen had also heard of fertile land that was for sale north of the Twenty, and in 1799, accompanied by a native guide and surveyor, Jacob Bechtel and a group from Bucks County, Pennsylvania, arrived in Waterloo County to scout out the area to survey its settlement potential. They were quickly followed by Joseph Schörg (Sherk) and Samuel D. Betzner, who are often credited with being the first two settlers to the area.15 Thus, in 1800 the influx of Pennsylvania German immigrants to Waterloo County began.

The journey they faced was long, slow, and arduous. Their passage through the Allegheny Mountains was difficult, and the group’s heavily laden Conestoga wagons often got stuck and needed to be unpacked, pulled along, and then repacked. As they crossed by barge at Black Rock (modern-day Buffalo) over the Niagara River, they suffered many unforeseen hardships.16 Along the way, the settlers battled thick mud (so deep that even dogs were lost in it); nearly impassable, bug-infested swamps; and forests that were filled with wild animals. At night, they slept in the woods in tents they had brought with them. Beyond Dundas, Ontario (the last outpost for supplies that they passed on their journey northward), there were no real roads. In fact, John Steckle points out that one “whole party spent about two weeks in making a corduroy road” through the dreaded Beverly Swamp just so they could get through it. Many of the settlers walked beside their wagons, roads or no, carrying tired children. The expedition took anywhere from four to seven weeks.

Once they arrived, the settlers’ survival depended upon their ability to erect shelter and provide food for the upcoming winter months — there would have been no real crops to harvest in their first year. But most of all, their survival depended upon their faith in God and, of course, on each other.17 It was said that in the first year following settlement, there was little food to spare and that even the peelings of potatoes were saved for planting the following spring. The potential for disaster was great, as were the real dangers of starvation and death.

Many of the Mennonite settlers kept journals and detailed their positive interactions with their Indigenous neighbours, who often could be found sleeping by the fire when the settlers awoke in the morning. Following a shared communal breakfast, they would exchange trade goods (Mennonite wives were known for their fresh-baked bread, which was gladly offered in exchange for haunches of venison). Pioneers like Joseph Schneider’s daughter Louisa fondly remembered the warm friendships that developed between them. As an old woman, Louisa mentioned that it had once been the custom of their Indigenous friends to bring gifts of handmade baskets to their home on New Year’s Day when she was a young girl. These friendships may very well have ensured the settlers’ ability to survive (and thrive) in their new homes.

Christian Schneider homestead (built 1807) c. 1900.

Although such accounts are unarguably useful when trying to discover the truth about the past, it is important to read historical overviews with caution, as some of these writings record only the successes. “Pioneer life was crude and brutish for most people. For every founding family that prospered, there were at least ten times as many who failed,” says historian Elizabeth Bloomfield. She tells us that we know less about the unfortunates and failures because they dropped out of township society and the local written record, moving back home or on to other settlement frontiers. Everyday tragedies like farming accidents, childbirth-related deaths, and disease claimed the lives of many family members and made more difficult an already tenuous existence. For those who stayed and those who managed to survive the odds of dying, diversifying their survival strategies became necessary coping mechanisms and perhaps the key to their success. In addition to their extended community of friends and family or Freundschaft, the Mennonites had a strong faith in God. They practised frugality and self-reliance, and, perhaps most importantly, they had an entrepreneurial spirit.

Many of the early settlers developed a secondary source of income that supplemented the money they received for the food they grew on their farms. For example, Mennonite pioneer Joseph Schneider18 erected a sawmill in 1816, while others planted large orchards and set up cider mills in their emergent villages. W.V. Uttley, in his 1937 account The History of Kitchener, points out that the production and sale of alcohol was also a viable commodity for some, adding that Schneider’s distant relation, “Indian Sam” Eby,19 was a distiller of whisky.

It is no surprise that mills of one form or another were among the first types of commercial structures in the area, which was known for its good (and plentiful) watercourses. In the early days, these were the key source of power for mills. For farmers, the mills were also their early social centres. As Frank Epp notes, “As the farmers cleared the land they became lumbermen and established sawmills. As agriculture expanded and barley was introduced, breweries were added to the grist mills; both flour and alcoholic beverages were considered essential to the social economy of the day.” Elizabeth Bloomfield observes, “a trip to the mill [often took] two or three days and [finding it] comfortable a farmer could meet other farmers] so that it became a social centre, and a business mart as well. They warmed their victuals and made coffee at the fireplace and slept on the floor or on the bags of bran.”

Abraham Erb was one of these early Mennonite millers. He invested heavily in the area and became a successful entrepreneur. He has been credited as being the founding father of the Village of Waterloo. When he came to Canada from Pennsylvania in 1806, he owned approximately four thousand acres of land, which encompassed much of what was to become the City of Waterloo today. Following his brother John’s20 example in Preston, Abraham established a sawmill and grist mill on Beaver Creek, a western tributary of the Grand River (where present-day Waterloo Park is located). Erb continued to contribute to his growing community in a variety of ways — he donated land for its first schoolhouse and served as Waterloo Township’s tax collector from 1822 until sometime before his death in 1830.

In time, each community within Waterloo County developed under the collective efforts of its respective constituency. Some of these settlements disappeared, as others merged into larger villages and towns. Some are still recognizable today, while others exist only as signs along the highway — a vague memory of a settlement that once was. What is certain, however, is that each contributed to the history of this region in its own way — perhaps not in the form of individuals’ life histories, but more as the collective struggles that each faced in the quest for viability and longevity. As the region grew and prospered over time, so too did the problem of containing those who didn’t quite “fit.”

![]()

2

TRANSIENT ENTERTAINMENTS:

A MENAGERIE (AND CHOLERA) COME TO TOWN

Community, in its most general sense, means all the people who live in a place or settlement and who are usually linked by their everyday business contacts and needs for shared services.

— Elizabeth Bloomfield, “Building Community on the Frontier: The Mennonite Contribution to Shaping the Waterloo Settlement to 1861”

BY THE SPRINGTIME OF 1834, things were looking up for the little village of Galt, Ontario. After many years of struggling to build a viable economy and attract new settlers to their community, the inhabitants were finally enjoying the rewards of their collective labour. It hadn’t been an easy ride, but their perseverance had certainly paid off.

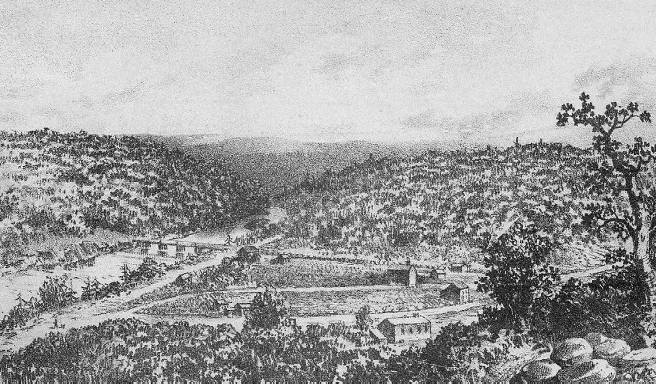

Artist’s rendition of the village of Galt in the early 1800s.

By 1821 the first tavern had appeared, offering simple accommodation for travellers passing through the area. In time, this was followed by connections to other larger communities — roads east to Guelph, south to Dundas (itself a trade nexus for the burgeoning pioneer agricultural market economy), and beyond, the roads to Hamilton and Niagara. The road north connected first with Preston, then Berlin, and, a bit farther away, Waterloo. The construction of these roads enabled travel to and from the area with greater ease. Galt was no longer an island, bounded by rivers and various watercourses. It was now connected with the outside world.

With backing from John Galt, the construction of businesses and homes flourished and these structures were soon complemented by the area’s first churches — First Presbyterian Church in 1831 and St. Andrew’s in 1833. Schools were another matter. Nearby Blair had founded the area’s first school in 1802 (the Rittenhouse School), but Galt needed one of its own. As James Young describes it in Reminiscences of the Early History of Galt, the village’s “first school, not erected until 1832, was a rough-cast “diminutive log building, situated where the Merchant’s Bank now is” located at “the head of Main Street.” By 1834 the population of Galt had reached upwards of two hundred souls.

Rural pastimes were few and far between in the early days. Following busy work days, events such as church picnics, occasional musical concerts, and imaginative games offered abidingly welcome entertainments for the common folk entrenched in their daily routines. So, it’s little wonder that when the news of an impending visit from a travelling menagerie (often incorrectly reported as a “circus”)21 first hit Galt in the spring of 1834, locals could hardly believe their good fortune. Excited by the then unparalleled revenue and tourism opportunities, many locals welcomed the chance to host the exotic exhibition, scheduled for July 28, 1834.

What they didn’t know was that death was heading straight for them. Within less than ten days after the performance, about one fifth of the greater community’s population would be dead.

I have always considered it odd that written accounts of the 1834 Galt cholera epidemic paid particular attention to the arrival date of the “Showmen with a Menag...