![]()

1

THE NEW WORLD BECKONS

Lamenting the loss of so many people to the New World, the Edinburgh Advertiser called for something to be done to stem the outflow of Scots. But even by this early date, in 1773, the exodus had developed an unstoppable momentum. High rents and oppressive landlords in Scotland, coupled with the positive reports of the better life to be had in North America, had led many people to opt for emigration. Having been amongst those who succumbed to the so-called “spirit of emigration,” some one hundred and ninety Scots had sailed to Pictou on the Hector in the very month and year of the newspaper’s pronouncement. Like the others who had gone before, they had made a deliberate choice to emigrate and were certainly not victims of any expulsions. Quite the contrary. They left against a backdrop of feverish opposition.

At this time emigration was seen as being highly detrimental to Scotland’s interests. Men were being lost who would otherwise serve in its workforce or armed forces. Some Highland landlords, fearing the loss of tenants from their estates, tried to halt the exodus, but to no avail. Our Hector arrivals had essentially defied Scottish public opinion and, as they stepped from their ship after a dreadful crossing, their immediate prospects looked bleak. It was not an easy beginning.

The Highlander statue in Pictou. The inscription reads “In proud commemoration of the courage, faith and endurance of the gallant pioneer passengers in the ship Hector.” Photograph by Geoff Campey.

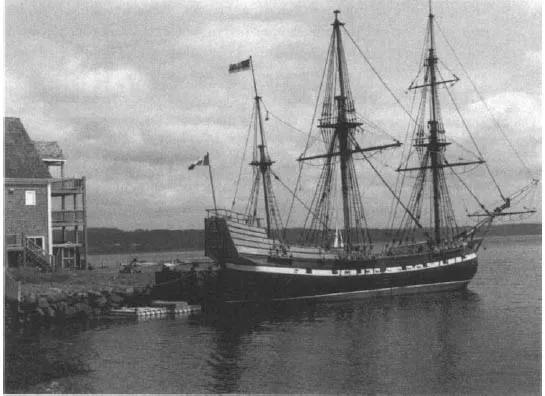

A larger-than-life bronze statue of a Highlander in full regimental dress now stands watch on a hillside above the Hectors landing place. From his vantage point he overlooks the modern-day replica which is now moored at the Hector Heritage Quay on the Pictou waterfront. Two hundred and thirty years ago a seagull perched on this same site would have witnessed the real thing — the historic landing of Nova Scotia’s first Scottish pioneers. It must have seemed deeply ironic to these founders of “New Scotland” that the people who came forward to greet them were New Englanders. This was already an English colony. The Nova Scotia which they saw before them was Scottish in name only.2

The region had attracted the attention of Sir William Alexander, Earl of Stirling, some one hundred and fifty years earlier. Having acquired colonization rights over “New Scotland” (or Nova Scotia, as it was designated in a Latin charter), he attempted to found a Scottish colony but his efforts came to nothing. Scottish lairds were happy to buy land but they had little interest in recruiting settlers.3 Lord Ochiltree came close to establishing a small colony in Cape Breton in 1629, but he and his settlers were sent packing by the French when he tried to extract tax revenue from local fishermen.4 When this property developers’ charade ended, the French settlements, which were mainly concentrated in the Acadian heartland around the Bay of Fundy, took on a new lease of life. While French-speaking Acadians were fast becoming a sizeable minority at this stage, they were greatly outnumbered by the Native inhabitants who were mainly Mi’kmaq.5

However, the situation changed drastically when France surrendered Acadia (peninsular Nova Scotia) to the British in 1713. The die was now cast. Britain bolstered her hold over Nova Scotia by exchanging its indigenous population for immigrants who could be relied upon to support her interests. The Native Peoples were systematically marginalized and thousands of Acadians were forcibly removed.6 After the Acadian deportation of 1755, some 8,000 American colonists of English ancestry arrived to take their place.7 These were the New England “Planters” who were brought, at government expense, to the Minas Basin region between 1759 and 1762.8

Nevertheless, in spite of this policy of expulsion, some Acadians remained in the region. Many had, in fact, escaped deportation in 1755 by fleeing to Ile Royale (Cape Breton) and Ile Saint Jean (Prince Edward Island), where they re-established themselves as settlers. But, once again, they were forced to surrender their lands. Another round of deportations took place in 1758 when British control was extended over these Islands.9 With the ending of hostilities in 1763, many Acadians later returned to the eastern Maritimes although they were confined to mainly remote areas and to relatively poor land.10 Thus, when the Hector arrived in 1773, Nova Scotia’s European population was largely of English descent. The Hector settlers would plant some settlement footholds but the dawning of their New Scotland was still a distant dream.

The ship Hector, a reconstruction. This replica of the original ship, which took nearly a decade to complete, is moored at the Hector Heritage Quay on the Pictou waterfront. Photograph by Geoff Campey.

The Highlander statue which overlooks Pictou Harbour deserves a closer look. This is a confident-looking young man, in full military dress, who holds his settler’s axe over his left shoulder and a musket in his right hand — appropriately enough, for a decade after the Hectors arrival at Pictou a good many Highlanders would come to the area as ex-soldiers. When the American War of Independence ended in defeat for Britain in 1784, the government relocated many ex-servicemen, at public expense, to areas such as Pictou, which it wished to protect.11 Thus, much needed military muscle and direction came to Pictou at a crucial time in its development. However, there was something particularly significant about these military settlers and their families. Most came from east Inverness-shire, in the northeast Highlands, — the place of origin of many of the Hector settlers. Lord Selkirk, one of the few high-ranking Scots to support emigration, saw for himself, during his travels through North America, why it was that “the same district of Scotland gathered round the same neighbourhood in the colonies.” The success of those who had gone before, in this case the Hector settlers, had been “a sufficient motive” to draw further people from their part of Scotland.12 Early links were being reinforced. This was the catalyst which would cause east Inverness-shire to lose so many of its people to Pictou.

The overall Scottish exodus was being fuelled by other factors as well. The disruption being caused by the introduction of large sheep farms, from the late eighteenth century, and a worsening economic situation were contributing to growing surges in emigration. Religious persecution lay behind the departure, in the early 1770s, of many hundreds of Catholic Highlanders, from parts of the Western Isles and mainland west Inverness-shire. They initially chose Prince Edward Island but, by 1791, they had also established settlements on the other side of the Northumberland Strait at Arisaig, in peninsular Nova Scotia. Catholic Highlanders were also to be found in Cape Breton, in spite of government regulations which were meant to keep them out. Wishing to protect its coal mining interests on the Island, the government had made Cape Breton as inaccessible as it possibly could to settlers. Legally binding restraining orders had been issued but Scottish colonizers took no notice of them. From 1790 they slipped across from Prince Edward Island and mainland Nova Scotia to the Western Shore of Cape Breton and helped themselves to the best land.

The fact that there were two, quite separate, concentrations of Scots, one Presbyterian and the other Catholic, can be attributed to Father Angus MacEachern (later Bishop). Based at the time at Prince Edward Island, he feared the loss of Catholic newcomers to Pictou’s growing Presbyterian congregation. Unless he intervened there was a real danger that Reverend James MacGregor, Pictou’s first Presbyterian Minister, would win them over as converts. So he devised a plan. As emigrant Scots disembarked from their ships, he effectively held up a signpost pointing Presbyterians towards Pictou and Catholics towards Arisaig and Cape Breton.13 By doing this, Catholic Highlanders were encompassed in a neat triangle on the east, which he could access by boat, and both they and the Presbyterians could expand their territories separately as they preferred to do.

The Scottish exodus from the Highlands and Islands grew rapidly because it offered people an escape from poverty and oppression. It held out the prospect of land ownership and a better standard of living. And it had another advantage as well. Highlanders could have opted for the good employment opportunities to be had in the manufacturing industries of the Scottish Lowlands. But this would come at a price. They would lose their cultural identity once they had become absorbed within the melting pot of an urban society. However, by emigrating to British America in large groups, they could transplant their communities intact and continue with their traditional way of life. Faced with these two alternatives, it is little wonder that so many Highlanders chose to emigrate. But thus far we have dwelt only on the factors which caused people to leave Scotland. We have still to consider why so many Scots chose to go to the eastern Maritimes.

One obvious reason was proximity to Scotland. Having a relatively short sailing time from Scotland, ports like Pictou were cheaper to get to, an important consideration for emigrants who had to struggle to find the money for their fares. Secondly, for many Scots the development of the eastern Maritimes’ burgeoning timber trade was another important factor. The Hector settlers had begun to export timber to Britain from as early as 1775, just two years after their arrival. And by 1803 when our roving reporter, Lord Selkirk, arrived on the scene “about twenty vessels at 400 tons on average” were loading up each year at Pictou Harbour.14 By 1805 the number had rocketed to fifty ships a year. And as greater numbers of ships arrived from Scottish ports to collect timber, many would come with a fresh batch of emigrant Scots in their holds.

As was the case elsewhere in the eastern Maritimes, Scottish merchants had been quick to spot the economic potential of the timber trade. By the early nineteenth century they were providing the region with a great deal of its early economic impetus and capital investment. Scots effectively controlled the region’s economic life. The Scottish-born timber merchant, Edward Mortimer, whose wealth and influence earned him the title of “King of Pictou,” was the lynch pin of Pictou’s economy.15 By offering Scottish settlers credit he gave them a stake in Pictou’s timber trade. Thus the timber trade provided emigrants both with the means of transport and with great economic benefits, once they became established as settlers. Having been the first Europeans to arrive in eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, they could choose the best coastline and river locations. They could profit most from the sale of their own cut timber and enjoy the overall benefits of living in a region with a rapidly expanding economy. And Mortimer’s preference for only doing business with his own people, ensured that Scots would always get the best opportunities.

To sum up, there were strong forces which caused people to leave Scotland, while the timber trade was the magnet which drew them to the eastern Maritimes. These “push and pull” factors together, with the early success of the Hector settlers, and those who followed them, fuelled a growing Scottish influx, which was dominated by Highlanders and Islanders. But their success was hardly a foregone conclusion. These people originated from areas of Scotland with few trees and limited agriculture — hardly the best qualifications for clearing an outback in North America. Yet they had other qualities which made them ideal pioneers:

Highlanders did succeed, not due to any practical skills which they brought with them, but because of their toughness and ability to cope with isolation and extreme hardships. When it c...