— ONE —

The Man Who Did Plant Trees

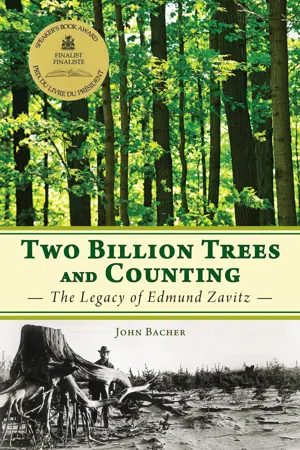

The summer of 2010 brought a barrage of global environmental disasters, bringing to mind Ontario of the early twentieth century, when the province had provided the stage for ongoing environmental disasters and loss of life. It was this type of scenario that propelled Edmund John Zavitz into public view. His mission: to rescue Ontario from further devastation. In 2010, massive forest fires in Russia engulfed Moscow in clouds of smoke that kept millions indoors, in fear of their lives, and threatened the security of nuclear power plants. Pakistan was gripped with a wave of floods that made millions homeless, unleashed landslides, devastated crops, and brought deadly epidemics.

Faced with this onslaught of foreign disasters, not one Canadian media pundit remarked on how these scenes of horror, then the staple of news coverage, were once commonplace in Ontario. From the late1880s to the 1920s, forest fires destroyed Northern Ontario towns so frequently that losing one’s home to a fiery inferno was seen as the price of living in the booming frontier. Floods that once engulfed communities such as London on the Thames, and Port Hope on the Ganaraska River, were as frequent as those of Karachi and Lahore, victims of the Indus River.

Much like the bleakest reports out of Africa today, describing the relentless march of the Sahara, descriptions of Ontario included the threats of two kinds of spreading deserts. To the north, rock deserts, much like the later moonscape of Sudbury caused by sulphur emissions, were expanding, the result of repeated forest fires burning away the thin soils of the Canadian Shield. To the south, deserts created by blow sand, caused by erosion, engulfed apple orchards, factories, and roads.

During his childhood, Edmund Zavitz’s mother, Dorothy, and his grandfather, Edmund Prout, told him stories about the devastation along the Oak Ridges Moraine. Some years later, in 1909, Zavitz photographed this scene of extensive erosion at the headwaters of the Ganaraska River near their farm, and lamented, “A river started here.”

Courtesy of Port Rowan-South Walsingham Heritage Association.

Those who were gripped by the mayhem of the news broadcasts of 2010 might have said, “There, but for the impact of Edmund Zavitz, goes Ontario.” His tripling of forest cover in Southern Ontario ended the threat of the marching deserts, which were termed “blow-sand conditions,” on lakeshores and moraines. His efforts were assisted by the introduction of new fire regulations, which he crafted, across all Ontario Crown lands, thus ending the blazing infernos that consumed soil cover in the boreal forest.

Zavitz’s rescue of Ontario from ecological degradation was a very long process, beginning with his employment as a graduate student in 1904, and ending with his death in retirement in 1968. His forestry reforms were based on regulations developed in Imperial India during the mid-nineteenth century through the creation of the Indian Forest Service. The regulations, which prevented clear cuts deemed too large to encourage natural regeneration and restricted livestock from grazing in forests, had been met with fierce resistance from vested logging interests seeking short-term profits. This bitter conflict became a drawn-out battle that was not resolved in Ontario until the 1940s.

This photograph, labelled by E.J. Zavitz as “Ganaraska Wasteland Photo #23,” reveals some of the humour that helped him mobilize his reforestation efforts.

In their comprehensive history of the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests, historians Paul Pross and Richard Lambert use the term “legendary figure” to describe E.J. Zavitz.[1] As these historians acknowledge, however, this term represents the way Zavitz was viewed in the last three decades of his life, the 1940–60s, by those who were employed by the Department of Lands and Forests. They viewed Zavitz as a powerful role model, one they emulated to excel in their work. Generally, with the exception of Norfolk County, which he also rescued from the threat of drifting sand, his work had limited public exposure.

When Pross and Lambert described Zavitz as a living legend, his policies had become “holy writ” for senior civil servants and parliamentarians of all parties in Ontario. This reality was movingly acknowledged in the then-premier John Robarts’s introduction to their book. Here, he praised not only Zavitz but the entire staff of the department, who were inspired by him. Zavitz appreciated his staff, recognizing them as well-trained and “authorized to take action” to combat serious threats like floods and forest fires.[2] When Robarts wrote his introduction, reforestation efforts were at their peak. Twenty-million trees were being planted annually, and ambitious tasks such as reforesting much of the Ottawa Greenbelt, which had been through astonishingly bold expropriations by the federal government, were underway.[3]

By the 1980s, under Robart’s successor William Davis, reforestation projects were on the decline. Provincial funding allowing conservation authorities (one of the most remarkable legacies of Edmund Zavitz) to acquire properties was being cut, significantly reducing their ability to acquire environmentally sensitive lands important for watershed protection, such as the Oak Ridges Moraine.[4]

While Zavitz’s watershed protection goals of reforestation in Eastern Ontario had been largely achieved by the 1980s, with an average rate of 38 percent forest cover, this was not the case in southwestern Ontario. Here, streams still suffer from flash conditions, becoming floods in the spring and bone dry the rest of the year, except when a big storm occurs. These cycles of floods and drought conditions lead to fish-habitat loss. Today, in Essex County alone, barely 5 percent of the total land has forest cover.[5]

Zavitz and the professional foresters who worked for him and whom he hired directly, such as his long-time assistant, A.H. Richardson, were well-schooled in the complexities of Ontario’s natural and human history. Both Zavitz and Richardson would encourage the conservation authorities they created to establish historical interpretation programs, like Black Creek Pioneer village. They wanted people to understand the impact pioneer practices had on the environment — like cutting down trees to make soap — and what could be done to rectify the damage. Using his extensive knowledge, Richardson ensured that new conservation authorities emphasized the teaching of watershed history to the general public.[6]

Zavitz’s reforestation work so improved the Ganaraska that today it is one of the best-forested watersheds along Lake Ontario. The beauty of this rural scene, showing the restored Ganaraska Forest, is one of the reasons that citizens do battle today to protect the landscape of the Ontario Greenbelt.

Zavitz’s success in Ontario was not a one-person miracle; his extended family played an enormous role. His father-in-law, John Dryden, gave him a political boost, and his wife, Jessie, provided exceptional support. Zavitz and some members of his team of professional foresters were also likely the only people to be close friends with the two most-bitter political adversaries of the 1920s — Ernest C. Drury (coalition government of United Farmers of Ontario and Independent Labour Party 1919–23) and Howard Ferguson (Conservative, 1923–30), who both served as premier of Ontario.

Zavitz’s personal style enabled him to launch popular movements, one of which led to the Conservation Authorities Act of 1946. This act, until the mid-1980s, provided 50 percent of the funds that the Ontario Conservation Authorities required for land purchases. Between 1937 and 1946, Zavitz became a great grey figure of eminence, operating in the background.[7]

In the late 1990s, the government of Mike Harris unleashed the Common Sense Revolution. As a result, provincial funding to conservation authorities was slashed, impeding Edmund Zavitz’s legacy of restoration work and reforestation projects. This funding reduction forced the sale of some previously protected forests and eliminated provincial reforestation stations. In encouraging this, Harris was radically accelerating trends endorsed over the past fifteen years by the governments of all three political parties — even the New Democratic Party participated. The party’s premier, Bob Rae, took to insulting public servants involved in forestry by suggesting they were so far behind the times in their practices that they...