- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The toxic nature of trauma can make it an overwhelming area of work. This book by a recognised expert adopts a systemic perspective, focusing on the individual in context. Very positively, it shows how every level of relationship can contribute to healing and that the meaning of traumatic experiences can be 'unfrozen' and revisited over time.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART 1

The Gateway to Practice

1

DIAGNOSTIC LABELS ACROSS THE LIFE SPAN

Introduction

This chapter reviews psychiatric diagnostic labels and specifically post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The diagnostic criteria for PTSD are presented. The process of stigmatisation and psychiatric labelling is discussed along with critical ideas regarding PTSD as a discrete diagnostic category. Some research in relation to PTSD is presented, including neurobiological explanations. The chapter offers a systemic critique of psychiatric diagnostic classifications. Life-cycle issues and the impact of context on behaviours can be used by systemic clinicians in their practice to ensure that diagnostic labels are pragmatically useful.

Psychiatric diagnostic labels

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) provide labels for human behaviours clustered by symptoms that often occur together. It is based on a medical model of illness.

A medical model makes a clear distinction between health and illness. A diagnosis is connected to a treatment plan, a prognosis, and is aimed at returning the individual to a state of health – ‘the way things were’.

Psychiatric labels are not ‘co-constructed’ between client and professional. Co-construction is a process of negotiation between people around the meaning of a communication. Within systemic psychotherapy it is connected to postmodern approaches (Boston, 2000) In postmodern approaches the clinician is not seen as an expert but as a ‘conversational partner’ (Andersen, 1987).

Within a medical model of diagnostic process, the client and clinician do not consider together the feelings or behaviours that have caused the client to seek help and then agree what these symptoms will be called. A diagnosis is given and sometimes changed with little discussion with or input from the client. Many clients have multiple diagnoses. Children and young people can receive a diagnosis at one stage of their life cycle that carries over into their adult lives, another life-cycle stage.

Receiving a diagnosis can become a passive experience, often followed by an acceptance of the ‘agreed’ treatment protocol as outlined in the UK by NICE, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2005). These treatment plans are based on research evidence that indicates the intervention which is considered to provide the best relief for the symptoms reported. While this process of diagnosis is more precise in the field of physical health, it is less reliable when it comes to mental health.

Stigmatisation

Mental health diagnoses are often seen as stigmatising. Occasionally some physical health diagnoses are similarly stigmatising – for example HIV/AIDS. Often this stigmatisation is based on fear and ignorance. It can also occur in conjunction with ‘either/or’ thinking which distinguishes those with mental health problems clearly from those without. Systemic thinking has in the main moved from such dualistic polarities to a more embracing ‘both/and’ position (Larner, 1994, p 11).

Diagnostic labels are not gender-, class- or race-equitable. This often leads to a minimisation of wider social factors impacting on health. Within mental health, for example, more women than men are diagnosed with depression; more boys than girls are diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); black people are over-represented as patients under the Mental Health Act. There is no intrinsic reason why these imbalances should exist, which encourages consideration of the wider social contexts impacting on individual functioning. Diagnostic categories are subject to social discourses which systemic clinicians understand as ‘clusters of stories including political, economic, and cultural … personal, family and community… ’ (Hedges, 2005, p. 3).

The DSM/ICD manuals go through fashions, where diagnoses leave and new ones enter. Take, for example, homosexuality, which was once considered a psychiatric illness. In 1973 the American Psychiatric Association called for removal of homosexuality from the DSM. It was removed and replaced in 1980 with ‘ego dystonic homosexuality’. It was not until 1986 that homosexuality as a mental disorder was removed completely from the DSM. Despite its removal, the vestiges of this pathologising of sexual choice can still be coded in the DSM under the category ‘Sexual Disorders Not Otherwise Specified’ where there is mention of ‘persistent and marked disturbance about one’s sexual orientation’. These modifications to a diagnosis reflect social and cultural changes about what constitutes a ‘mental illness’.

The DSM/ICD diminishes the role of poverty, racism, classism and sexism, all of which link to poor mental health outcomes. This can be seen, for example, with looked-after children, who become ‘looked after’ because they have suffered ‘significant harm’ – a legal term emerging out of UK civil childcare law. Civil courts determine whether the threshold has been reached – has the child suffered or is he or she likely to suffer ‘significant harm’? If the answer is ‘Yes’ the court may decide the child should no longer remain in the care of their family.

‘Significant harm’ is unequivocally a lived experience caused by variables external to the child. However once a child enters the ‘looked-after system’, they become subject to a discourse of psychiatric labelling. The rates for ‘psychiatric disturbance’ in the looked-after children population are considerably higher than for the general population – 45 per cent, a conservative estimate, compared to 10 per cent in the general population (Meltzer et al., 2003; Meltzer, 2005). Yet the obvious discourses about the impact of adverse childhood experiences (often traumatic) on child mental health remain conspicuously absent in the literature. So an extrinsic experience of ‘significant harm’ becomes an ‘intrinsic’ experience of ‘mental illness’.

Post traumatic stress disorder – the diagnostic category

The diagnostic category post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) needs to be placed in an historical/hysterical context. Its history reflects wider social factors and lived experiences. The large numbers of men returning from wars showing a typical constellation of behaviours led to the establishment of PTSD as a separate diagnosis. Originally labelled ‘shell shock’ after the First World War, it was seen as a form of hysteria. With the psychological consequences of further wars (most notably the Second World War and Vietnam) impacting on generations of families across the globe, PTSD became part of many people’s lived experiences.

With increasing globalisation (including media and migration) the impact of war and exposure to other traumatic events has spread far beyond immediate geographical boundaries. This has moved PTSD into common parlance and experience.

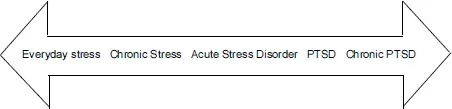

PTSD can be reliably diagnosed, often in conjunction with other psychiatric conditions. Not everyone exposed to a risk factor (or the same traumatic experience) develops a PTSD. There is good evidence to suggest that even indirect exposure to traumatic events can generate symptomatic behaviours (Otto et al., 2007), whether this is through media exposure or familial experience. The former (witnessing trauma via the media rather than personally experiencing it) has been dubbed ‘post-traumatic stress disorder of the virtual kind’ (Young, 2007, p. 21). Research suggests that trauma is very common, with more than half the ‘normal’ Western population experiencing a traumatic event (Norris and Slone, 2007). Over the life cycle, the chance of experiencing a trauma is put at 69 per cent (Resnick et al., 1993). PTSD is part of a continuum of stress (this is represented in Figure 1.1).

From this large group of people exposed to a traumatic experience (69 per cent), only a small proportion goes on to develop clinically significant PTSD. In North America the figure is between 10 and 20 percent (Norris and Slone, 2007).

There are a number of factors considered to increase the risk of developing a PTSD. These include the following:

1. Fear at the time of the traumatic experience, particularly a perceived threat to life.

2. Dissociation or a pervasive feeling of detachment from personal experience after the traumatic event.

3. Poor family functioning, including parental mental health problems after the traumatic experience.

(Andrews et al., 2000; Ozer et al., 2003; Trickey, 2009; Trickey and Black, 2000).

Figure 1.1 Continuum of Stress

The last factor, poor family functioning after the trauma, emphasises the importance of working with families (and communities) as part of reducing risk and possibly the severity and length of psychological disturbance following traumatic events. For children and young people, it clearly indicates that supporting parents and assessing parental mental health can be essential in promoting the child or young person’s recovery. This underlines the usefulness of systemic perspectives in dealing with trauma over the life cycle.

PTSD as a diagnostic category includes delayed onset – allowing for considerable time to pass from the traumatic event to the presentation in a clinical setting. Many clients may not have made a connection between their current somatic experiences and/or emotional distress and earlier traumas.

For example, Jimmy spent much of his childhood in an Irish orphanage where he was subjected to abuse by the staff. In his sixties, he joined with other care survivors to claim compensation for his suffering. He had never been diagnosed with PTSD.

Your diagnosis of my situation was a great help to me and explained much, of which I had previously been ignorant. With PTSD, there is great after effects and at times seem ongoing through life. I still to this day suffer terrible flashbacks and memories.

In Jimmy’s case the diagnosis of PTSD made sense of his lived experience. It also confirmed that his childhood abuse experiences continued to influence his adult life, often in unhelpful ways.

PTSD is seen primarily as an anxiety disorder – with the anxiety having a very distinct quality (Brewin, 2007). There is no secondary processing – no associative representations of the traumatic experience (Verhaeghe, 2004). This is particularly important for systemic clinicians who rely so heavily on narrative interventions which depend on those associative processes.

Much recent discussion about neuropsychology and emotion imply that when the brain’s cortex is switched on during conversation, individuals can access words to describe the feeling states that are emerging. However there are times, as in highly stressful, life-threatening situations, when this is not possible. It is not a purposeful switching-off but is automatically triggered by an event (internal felt experience or external stimuli) – an event the individual may not be consciously aware of.

Clinical vignette 1.1 comes from a session where a young girl has been referred to a CAMH service because of her uncontrollable temper.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE 1.1 | ||

Speaker | Spoken conversation | Clinical reflections |

Mother | It is like this blind rage appears and takes over. (describing her 11-year-old daughter) | ‘Blind Rage’ is the label given for the symptomatic behaviour. This will be tracked through the session. ‘Blind Rage’ lends itself to externalizing because it ‘appears and takes over’ – the mother sees it as separate to her daughter. |

Clinician | Do you know when this is happening? (to daughter) | In checking this out with the daughter consideration is being given to whether she feels she has any control and if this is a traumatic enactment. |

Daughter | Not really. Just after … I really need to change my behaviour. (crying) | The response … ‘just after’ suggests that during the ‘attack’ she is dissociated. The crying increases the emotional tone of the session. |

Clinician | Do you recognize this blind rage? Is it something you have seen before? (to mother) | Moving back to speak with mother is an attempt to keep the emotional tone manageable and to broaden the discussion out. |

Mother | Yes but I don’t want to talk about it. | The response suggests a strong affective association for the mother to her daughter’s behaviour and avoidance on mother’s part to talk about it. This suggests that trauma is very likely a part of the presenting problem. |

A history of domestic violence is recorded in the referral. The session is attended by mother and daughter. The child’s mother is describing the symptom. Clinical vignette 1.1 is a good description of what may be referred to as an amygdala hijack (Goleman, 1996). The girl has little or no awareness about why it happens and when in the grip of one of her rage attacks appears powerless to stop them. When calm, as she was in most of the sessions, she was engaging, cooperative and very sweet. It was hard to imagine what her mother was concerned about. Perhaps the clue comes from mother’s comment that the ‘blind rage’ is something she has seen and/or experienced herself before but d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 The Gateway to Practice

- PART 2 The Field of Practice

- PART 3 The Practice Neighbourhood

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Working with Trauma by Gerrilyn Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Psicoterapia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.