![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

The major cities of the world have undergone transformation since the 1980s. City centres, skylines and waterfront developments appear to be similar wherever you happen to be. Cities compete to build the tallest buildings in the world. New York provided the model that was to be envied and imitated, especially after it escaped from near bankruptcy in the 1970s. The booming La Défense office quarter in Paris marketed itself as ‘Manhattan sur Seine’. This quickly became ‘Tokyo sur Seine’ as the strength of the Japanese economy pushed forward the global claims of its capital. Deregulation of financial markets, the dramatic transformation of London Docklands and new cultural attractions firmly established London as one among the leading group of cities. London, New York and Tokyo were singled out as the ‘global cities’ in Saskia Sassen’s influential book in 1991. Economic globalization has been the driving force of this change. Whereas in the past world cities were defined by their imperial roles (e.g. Vienna, Berlin) or by the size of their population, the new world leaders are there because of the economic role they play in globalization. Above all they are the financial hubs of a new economic system. As we will see, many people have created hierarchies of cities according to their position in this new economic order, stemming from the pioneering work of John Friedmann (Friedmann and Wolff, 1982; Friedmann, 1986). However, in a globalizing world these positions are not fixed. In the period we cover in this book we see the rise of urban China and the world city claims of Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing with even more dramatic skylines.

Economic globalization seems to be the driving force behind urban change but is this process of globalization the full story? How inevitable is it that cities follow the same path? A central aim of this book is to question the view that the leading world cities are all moving in the same direction, spurred along by the imperatives of globalization. In fact, the responses to the forces of economic globalization in different cities across the world have been very diverse. While in some cases they are accommodated enthusiastically, in others they have been moderated, steered or even confronted. We examine these differences and debates about how cities have followed different paths, focussing particularly on the consequences for their strategic planning agendas.

Globalization certainly sets challenges for city politics and policy. We look at how these challenges are tackled and take the view that city politics matters. The decisions made by political leaders with national, regional or local mandates have the potential to shape the future of the city. Many city leaders have taken a limited view and respond to globalization by focusing on making their city more competitive. This has led to a determination to provide facilities aimed at capturing economic advantage in the changing global economy. City leaders have to be sensitive to the demands and views of international capital and to those of their local citizens. The way that this global/local interface is politically managed at the urban level is, in our view, a key element in determining the degree of variation between world cities. In analysing similarities and differences across world cities we thus focus on the interaction between the forces of globalization and the urban political response.

Debates on globalization and the formation of world cities often take place at a generalized level. Some argue that cities have lost their importance as globalization destroys the relevance of specific locations. Geographical space is replaced by a space of ‘hypermobility’ or flows, particularly in relation to financial capital. But economic activities and people are embedded in real places. In our view cities are even more important as locations where global activities are localized and competitive economic advantages created. To progress these debates and illuminate the differences of opinion, we believe it is necessary to ground them in the particularities of urban politics in specific cities and to analyse specific policies. A strategic urban planning policy is particularly pertinent because it is involved in the task of balancing broader economic pressures and local needs. It is at the forefront of managing global/local tensions. Our analysis therefore moves from a critical review of the context-shaping forces of economic globalization, through understandings of the processes of urban governance, to the agencies and interests shaping the specific form and content of strategic planning. We trace a path through the wide-ranging literature on globalization and governance to set our framework for the analysis of particular city responses.

In looking for the origin of the term ‘world city’ many people mention the well-known book of that title by Peter Hall which was first written in 1966 and ran to three editions (Hall, 1966, 1977, 1984), although Hall himself refers back to the work of Patrick Geddes in 1915. Hall’s work is particularly relevant to our discussion as he concentrated on the planning approach in this category of cities. However, he was writing before the advent of the current phase of globalization and his definition of world city is rather different from that used in the contemporary debate. He describes world cities as those that are usually the major centres of political power, seats of the most powerful national governments, sometimes international authorities and government agencies of all kinds. Round these gather big professional organizations, trade unions, employers’ federations, centres of culture and knowledge, and headquarters of major industrial concerns. He does not explore in detail how his definition relates to his actual choice of cities. However, as we will see in Chapter 3, there has been a move to a more rigorous definition of the world cities concept linked to the new processes of economic globalization. This concept has generated considerable debate which we will be exploring. There is a large volume of literature discussing the most important cities and the particular role they play in global networks. Many authors have tried to develop a hierarchy of importance and there is widespread agreement that New York, London and Tokyo are special and lie at the top. Some cities, such as Paris, may try to challenge the dominance of these top cities while others may play an important role in their regional economy, such as Miami. There are also many sub-categories of cities that researchers use to show the claims of different cities in a global economy, such as ‘gateway cities’, ‘global media cities’, or ‘regional capitals’. Many authors talk about ‘globalizing’ cities to indicate that almost all cities are caught up to some degree in an interaction with global forces. The situation is not static. Within world city hierarchies that are based on economic connectivity, cities can rise and fall in importance. So, for example, we explore whether Tokyo, at the top of the hierarchy, is losing its leading position, and whether cities such as Mexico City or Shanghai are entering a new phase with greater world importance. Do the efforts of ‘rising’ cities place new pressures on the resilience of older world cities? Can New York still claim to be the ‘capital of the world’?

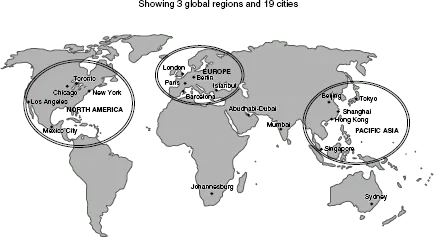

The core global regions

As we will see in our explorations in Chapter 2, much of the recent literature on globalization discusses the increasing connectivity across the world. Economic actions in one part of the world have wide global ramifications elsewhere. However, such global networks and flows are not evenly spread. There are certain parts of the world where most interactions take place and other parts that are more economically isolated. Even within the most connected part, we will see that there is a debate over the degree to which this forms a single global economic entity or is made up of three regions with their own degree of internal cohesion. For example, the periodic crises of the international economy, in East Asia in the late 1990s and in North America and Europe since 2008, can be said to have had the greatest impact on cities within their own regions. One assessment of the recent economic crisis is that economies are certainly internationalized but not global (Thompson, 2010). Such an assessment reinforces a view of a world that may be increasingly globalized but at the same time will have distinctive economic regions. One question we explore is the extent to which the histories and traditions of each global region lead to different outcomes in world cities. Europe, North America and Pacific Asia, which can be called the core regions, host the established world cities of London, New York and Tokyo and within each region there are dense interconnections between cities, people and money. We use this idea of three core global regions to organize the exploration of particular cities in this book (Map 1.1). We will pay a lot of attention to London, New York and Tokyo but we also look at some twenty other cities in these regions that aspire to play a world role, based on their connectivity to the global economy.

Therefore our choice of cities is based upon their degree of incorporation into the global economic system. Some of the largest cities in the world, sometimes referred to as mega cities, lie outside the core regions. However, pure population size does not necessarily lead to global economic linkage and so such cities are not included in our study. Nevertheless, a phenomenon of recent years has been the increasing linkage of a few key cities in the less-developed regions of the world. The BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) or the BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, China) groupings are seen as vitally important blocks of growing economic influence and significance in institutions of global governance. We will therefore briefly review some of these cities that have been playing an increasing ‘gateway’ role in linking such subregions into the world economy. Chinese cities are included in our coverage of the Pacific Asia region, but we also explore some of the new strategic planning issues that are developing in Mumbai, Johannesburg, Abu Dhabi/Dubai, Sydney and Istanbul. However, while we can find similarities in approach to strategic planning across cities, the high levels of poverty and inward migration in cities of the ‘global south’ can lead to different political and policy pressures. For example, as Roy (2008) puts it, sometimes ‘as cities in the global South grow rapidly so these cities have adopted rather vicious forms of urban planning – a criminalization of urban poverty, a focus on highly privatized forms of development, (and) state-sponsored forms of sprawling peri-urbanization ...’ (p. 253).

Map 1.1 The major world cities

So, our view is that the impact of economic globalization on these cities is mediated in important ways by their regional context. As we have already said, we also think that governance and politics matters. World cities do not simply develop and change on a tide of global flows of finance, people and media images. Localized decisions are made about the direction of change and scope of public policy. The fate of cities depends on global forces, regional influences and local choices. We challenge the perception that economic globalization creates inevitable impacts – a view that has come to dominate the policy agenda. To do this, we think it is essential to analyse the links between economic forces and political decision-making. It is our view that it is only through a multidimensional approach that the full picture can be seen and understood. The framework we adopt links economic globalization, debates on the transformation of world cities and the scope for political choices – an investigation that integrates the processes of globalization, changes in world cities and governance. We then use this framework to analyse the different strategic planning responses in the cities we cover. We believe that this multilayered and wide-ranging approach provides a unique and innovative statement on how cities across the world are being reshaped.

Comparative study always requires careful attention to methodology to avoid mere juxtaposition of descriptive accounts. One issue at stake is whether the approach to the research influences the conclusions. For example, an approach that focuses on the special cultural and historical conditions of particular cities is more likely to conclude that cities vary than one that focuses on global economic influences. In our approach, we seek a way that can weave together both general and specific factors – that can combine global forces and local actors and conditions. Our comparative framework starts with the structural context of economic globalization. We consider that structural approaches to comparative study need to be integrated into an understanding of the cultural variation between governments and the differing roles of political actors – factors that help steer the direction of urban policy. However, global forces are not so easily distinguished from local forces. Drawing on Tilly’s (1984) distinction between ‘encompassing’ and ‘variation seeking’ approaches to comparative studies, we set out a framework that allows for an examination of the encompassing impacts of world city status and economic competition alongside an appreciation of the historical, cultural and local processes that may make a difference and allow different approaches in different cities. We take a more multidimensional approach to the factors that might cause similarity and difference than that taken in some of the literature. We want to expose the variation between cities, but at the same time we do not want to lose sight of the broader framework that knits together globalization, world city and governance. The combined approach establishes a focus on the management of world city ambitions across a range of cities but links this into a range of broader debates – for example, those that suggest a convergence in urban policies in the face of globalization.

In our approach, we have chosen to explore the last thirty years or so as it is during this period that the forces of economic globalization have taken a new turn. We go back to the 1980s when, in many of the cities we examine, specific concerns about economic competitiveness and world city status began to emerge. By the end of the 1980s the dual world system of West and East had ceased to have relevance and the idea of globalization appeared more and more in academic and policy discourse. We take this medium-term perspective, rather than focusing only on the present, to answer questions about how cities have adapted and changed as global and regional economic pressures impact upon them.

The spatial dimensions of governance

So we believe politics matters. However, politics operates at a number of interconnecting levels. Governance itself has to be investigated across spatial scales encompassing global and sub-global regions, national and local. At the global level we need to understand the imperative of economic globalization and the way in which it impinges upon cities. We need to explore global regional variation – for example, the different traditions concerning the degree of state intervention. We then need to ask whether national governments still play a role and explore the often complex arguments about the role of the state. At the local level we need to understand how the different constellations of local interests influence the way in which these global and regional forces are interpreted and embedded in the local decision-making processes.

Institutions of global governance – the International Monetary Fund (IMF), UN-HABITAT and World Bank for example – set wide ranging standards for cities. The UN’s climate change conferences also have considerable impact on the development of national and urban policy. However, agencies such as the IMF and the US government have had a particular view on globalization, forming an approach that has sometimes been referred to as the Washington consensus. This saw the inevitable adaptation of all national economies to the new global economic imperative. Their globalization project can be regarded as an ideological position that constrained alternatives. In recent years, such views and actions have faced increasing opposition and have been buffeted by economic crises. In 1976 the seven largest national economies of the time, (the US, Canada, Japan, Germany, the UK, France and Italy) formed a Group called G7, and national finance ministers met several time a year to discuss economic policy. However, in 2009, in the wake of the international financial crisis this group was superseded by the G20. This larger group is indicative of the growing importance of other countries in the global economy, such as China, India and Brazil. Again the finance ministers meet regularly, together with representatives from the IMF and the World Bank, to discuss the global economy. This larger grouping encompasses about 85 per cent of the world GNP but only about two-thirds of its population. As an influential but self-appointed body, this broader grouping still draws street demonstrations to the cities selected for meetings. Civil society has also become globalized.

In our three global regions we have seen the establishment of organizations such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the European Union (EU) and the APT (ASEAN plus 3). These organizations have arisen in recent years to coordinate issues of economic policy in their regions. As a result, nation states have transferred some of their sovereignty to this higher level. However, there is considerable variation among the three regional organizations. The EU is the most developed with the legitimacy to operate across a wide range of policy areas and takes a lead in global discussions about climate change. The others are more limited to issues of trade, although differing considerably in the way they regard the state/market relationship.

At the national level the debate about the changing nature of the state has a particular importance for our work. Planning is usually a state activity and will therefore be affected considerably by any reconfiguration of the state. The global prescriptions of neo-liberalism – privatization, decentralization – have reached almost all sub-national governments. The interplay between the levels of governance, including the role of national, regional and local states, is a central feature of our framework. Thus any change that is taking place in the way that this interplay of levels operates is a key concern. The globalization debate includes a discussion of the future of the nation state. Some authors claim that we are witnessing its decline to a marginal role. On the other hand international treaties are negotiated by these nation states and, certainly in Europe, national welfare states and planning systems mediate international pressures. And it was the nation states that led the response to the banking crisis in 2008. As we will see in later chapters, some authors talk about the restructuring of the state – some functions moving upwards to the global-regional level and some decentralized to local government. The nation state may also be taking on some new roles. This rescaling process is clearly a central issue in determining the way that decision-making power is distributed, and affects the strategic planning agenda of cities. One interpretation of these changes is that city government will become more important. Some city leaders have been developing their own international networks and seeking a stronger voice for world cities, in the debate about climate change for example, and have been more active in city networks exchanging ‘best practice’.

City governance is central to an understanding of the strategic planning approach of any city. The priorities of the plan will be expressed through political decisions. However, mayors and other public agencies do not have a free hand. Other interests influence city politics. Some international businesses, for example, will want to prioritize world city issues and persuade politicians to accommodate to economic global forces. On the other hand social movements, from within the city or transnational, may also arise to oppose such views. Strategic planning decisions may, in some cities, offer an arena in which such conflicts can be played out. Cities will differ in the degree to which civil society is active and in the range of participatory opportunities that are available. There is a world of difference between referendums in L...