- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Non-Democratic Regimes

About this book

A comprehensive assessment of the nature and evolving character of authoritarian regimes, their changing character and the main theoretical explanations of their incidence, character and performance. The third edition covers the rise of new forms of disguised dictatorship and semi-competitive democracy in the 21st Century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

1

Theories of Non-Democratic Government

Although there are no widely recognised general theories of non-democratic government, there are many theories of such particular forms of non-democratic government as totalitarianism, authoritarianism, communism and fascism. Being concerned with forms of government, these theories are less interested in the traditional regime-defining question of ‘who rules?’ than in the wider question of ‘how do they rule?’, which involves such issues as the regime’s methods and degree of control over society, its ideological or other claims to legitimacy, its political and administrative structure, and the goals that it seeks to attain.

Therefore, although such terms as ‘totalitarian’, ‘authoritarian’, ‘communist’ and ‘fascist’ are used to describe regimes as well as forms of government, these labels say much more about a regime than whether it is a military or a party dictatorship (and in fact the term ‘authoritarian’ can be applied to both types of dictatorship). In contrast, to label a dictatorship as a ‘military’ or ‘party’ regime is to describe only the type of regime, in the sense of military or party rule, not the form of government – which in the case of party rule could be either totalitarian or authoritarian, communist or fascist.

Only theories of totalitarian and authoritarian forms of government will be examined in this chapter. The notions of ‘totalitarianism’ and ‘authoritarianism’ are general enough to have been applied (not necessarily very successfully) to a relatively wide range of regimes, including those labelled communist and fascist. Moreover, the distinctive features of communist and fascist forms of government will be described in later chapters, especially those on legitimacy and control (Chapter 5) and on policy and performance (Chapter 6).

Totalitarianism

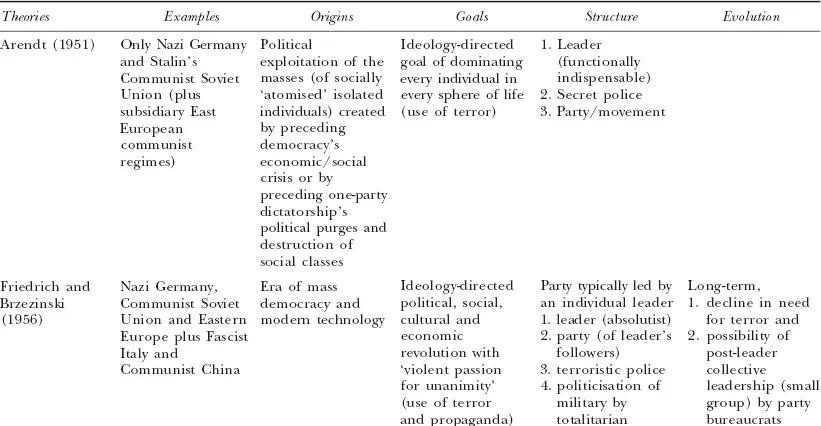

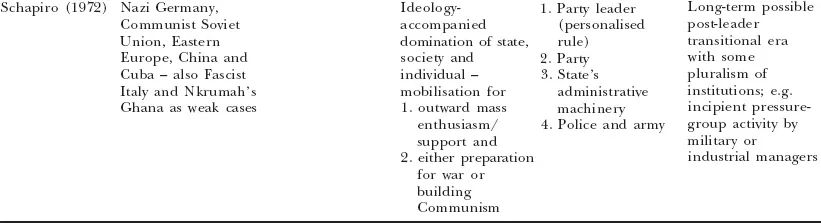

The theories of totalitarianism are the most distinctive and imaginative of those developed by theorists of non-democratic government (see Table 1.1). The term ‘totalitarianism’ emerged in the 1920s–30s as part of the ideology of Fascist Italy: the Fascist ‘totalitarian’ state was pithily described by Mussolini as ‘everything in the State, nothing outside of the State, nothing against the State’. But in the 1950s totalitarianism reemerged as a prominent concept in Western political science and was used to describe communist as well as fascist regimes. The classic works of Arendt and of Friedrich and Brzezinski provided descriptive theories of totalitarianism (in the sense of offering a much broader as well as a deeper understanding of the concept) which claimed that it was a quite new and ‘total’ form of dictatorship. In fact theories or concepts of totalitarianism were for years the leading or most dynamic approach to the study of non-democratic regimes; but from as early as the 1960s onwards there was a growing body of opinion that the notion of totalitarianism had outlived its usefulness. And, despite the work of such second-generation theorists as Schapiro, the notion of totalitarianism has never recovered the prominence that it enjoyed in the 1950s–60s.

Arendt’s Classic Theory

Arendt’s 1951 pioneering work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, depicted totalitarianism as a new and extreme form of dictatorship. In her view there had been only two examples of totalitarian dictatorship – Hitler’s Nazi regime and Stalin’s communist regime. More precisely, totalitarianism had existed in the 1938–45 years of Hitler’s Nazi dictatorship in Germany, in the post-1929 years of the communist dictatorship in the Soviet Union, and in post-Second World War Eastern Europe, whose newly established communist regimes were viewed by Arendt as only extensions of the Soviet-based communist movement (1962 [1951]: 419, 308 n. 10).

She downplayed the ideological/policy differences between the rightist Nazis and leftist communists, declaring that in practice it made little difference whether totalitarians organised the masses in the name of race or of class (ibid.: 313). In contrast, only a year later Talmon emphasised the distinction between Left and Right totalitarianism in his famous work on what he termed the ‘totalitarian democracy’ associated with the French Revolution (1952: 1–2, 6–7). He argued that only totalitarianism of the Left was a form of totalitarian democracy, for the Right totalitarians were concerned with such collective/historic entities as state, nation or race and viewed force as permanently required for maintaining order and social training. The significance of the differences between left-wing (communist) and right-wing (fascist) variants of totalitarianism has remained an awkward issue for theorists and users of the concept of totalitarianism.

Although Arendt did not view totalitarian regimes’ ideological differences (or even ideological content) as very significant, she noted that ideology plays an important role in such regimes (1962: 325, 458, 363). Totalitarian ideology’s desire to transform human nature provides the regime with a reason as well as a road map for the all-pervading totalitarian organisation of human life, as only under a totalitarian system can all aspects of life be organised in accordance with an ideology. Furthermore, ideology in turn provides a means of internally, psychologically dominating human beings and therefore plays an important role not only in the totalitarian organisation of all aspects of human life, but also in attaining the ultimate totalitarian goal of total domination.

One of the features of Arendt’s theory of totalitarianism is the extreme and total goal that she ascribed to this form of dictatorship. For totalitarianism seeks ‘the permanent domination of each single individual in each and every sphere of life’ and ‘the total domination of the total population of the earth’ (ibid.: 326, 392). A totalitarian movement’s seizure of power in a particular country therefore only secures a base for the movement’s further global expansion. But taking control of a country also offers the opportunity to experiment with organising and dominating human beings more intensively as well as extensively, and thereby subjecting society to ‘total terror’ (ibid.: 392, 421–2, 430–5, 440). After the secret police have liquidated all open or hidden resistance, they begin to liquidate ideologically defined ‘objective enemies’, such as Jews or supposed class enemies. This uniquely totalitarian level of terror is in turn replaced by a third, fully totalitarian stage. Now everyone seems to be a police informer and the secret police not only seek to remove all trace of their victims, as if these people had never existed, but also randomly select their victims. However, the ultimate ‘laboratories’ for experimenting with total domination are the regime’s concentration, extermination or labour camps, where terror and torture are used to liquidate spontaneity and reduce human beings to only animal-like reactions and functions (ibid.: 436–8, 441, 451–6).

Unlike most later theorists of totalitarianism, Arendt was willing to take on the difficult task of explaining the origins of totalitarian regimes (though her explanations have never found favour with historians). She argued that these regimes arise from totalitarian movements’ organisation of ‘masses’, in the sense of people who are experiencing social atomisation and extreme individualisation – the main characteristic of ‘mass man’ is social isolation created by the lack of normal social relationships (ibid.: 308–17). Such people are more easily attracted by totalitarian movements than are the sociable, less individualistic people who support normal political parties. If socially atomised masses also constitute (or are joined by) masses in the sense of sheer numbers, they can produce such a powerful totalitarian movement that a totalitarian regime can be established.

Socially atomised masses were created in a very different fashion in the Soviet Union than in Germany (ibid.: 313–24, 378–80). The Nazi movement came to power by winning the support of socially atomised masses that were created by the economic, social and political crises afflicting democratic Germany in the early 1930s. But in the Soviet Union the socially atomised masses were created after the communist movement had established a one-party dictatorship. Under its new leader, Stalin, the communist dictatorship created such masses by the destruction of the semi-capitalist class structure and by extensive political purges. Paradoxically, the victims sought relief from their social atomisation by offering total loyalty to the Communist Party, even though it was dominated by the perpetrators of the purges – Stalin and the political police.

The prominent role played by the political/secret police (as elite formations and super-party) is a unique structural feature of totalitarian regimes, but the key and most distinctive structural feature is the functionally indispensable leader figure – the Stalin or Hitler (ibid.: 380, 413, 420, 374–5, 387). A totalitarian regime and movement is so closely identified with the leader and his infallibility (as interpreter of the infallible ideology) that any move to restrain or replace him would prove disastrous for the regime and movement. His subordinates are not only aware of his indispensability, but have also been trained for the sole purpose of communicating and implementing his commands. Therefore the leader can count on their loyalty to the death, monopolise the right to explain ideology and policy, and behave as if he were above the movement.

Friedrich and Brzezinski’s Classic Theory

Friedrich and Brzezinski’s 1956 Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy provided a more detailed and widely applicable descriptive theory than Arendt’s (see Table 1.1). The newer theory’s examples included post-1936 Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and communist Soviet Union plus the newly established communist regimes in Eastern Europe and China (though it was acknowledged that Fascist Italy was a borderline case). But the most distinctive and important aspect of the theory was its claim that the ‘character’ of totalitarian dictatorship was to be found in a syndrome of six interrelated and mutually supporting features or traits (1961 [1956]: 9):

1. an ideology;

2. a single party, typically (that is, not always) led by one person;

3. a terroristic police;

4. a communications monopoly;

5. a weapons monopoly; and

6. a centrally-directed economy.

However, it was acknowledged that the six-point syndrome had shown ‘many significant variations’, such as the striking variation in economic structure arising from the fascist regimes’ retention of a form of private-ownership economy instead of shifting to a state-owned/collectivised economy as the communists had done in the Soviet Union (ibid.: 10).

TABLE 1.1

Theories of totalitarianism

In fact Friedrich and Brzezinski, unlike Arendt, went on to address the awkward issue of whether the differences between communist and fascist regimes outweigh the totalitarian similarities (ibid.: 7–8, 10–11, 68, 57, 77). They argued that communist and fascist totalitarian regimes are basically alike but by no means wholly alike, and they pointed to differences in origins, political institutions and proclaimed goals. In a later discussion of totalitarian ideology’s link to international revolutionary appeals (and to the leader’s ambitions for world rule), they again pointed to the difference between communism’s supposedly global, class-based appeal and fascism’s appeal to a particular people. Yet despite these significant differences, Friedrich and Brzezinski maintained that communist and fascist regimes were sufficiently similar to be classed together as totalitarian dictatorships and to be distinguished from older types of autocracy, none of which had displayed the totalitarian six-feature syndrome.

Like Arendt, these two later theorists viewed totalitarianism as an extreme, ideologically driven and terror-ridden form of dictatorship (Friedrich and Brzezinski, 1961: 130–2, 150, 137). The regime’s ideology is the ultimate source of the goals that the totalitarians seek to attain through a political, social, cultural and economic revolution. Totalitarianism is in fact an actual system of revolution, requiring a state of ‘permanent revolution’ that will extend for generations and applies to even such prosaic matters as fulfilling economic Five-Year Plans.

The use of terror is stimulated not only by the ideology’s extensive revolutionary goals, but also by its supposed infallibility. The totalitarians’ commitment to their ideology’s infallibility produces a ‘violent passion for unanimity’; after the destruction of the regime’s obvious enemies, the terroristic police turn their attention to the rest of society and even to the totalitarian party itself – ‘searching everywhere for actual or potential deviants from the totalitarian unity’ (ibid.: 132, 137, 150).

But Friedrich and Brzezinski took a less extreme view than Arendt of totalitarian terror. They pointed to ‘islands of separateness’, such as the churches and universities, where a person could remain aloof from the terror-accompanied ‘total demand for total identification’ (ibid.: 231, 239). And they argued that the level of police-inflicted terror may eventually decline as terror is internalised into a habitual conformity and new generations of society are raised as fully indoctrinated supporters of the regime (ibid.: 138).

In fact the regime relies on its ‘highly effective’ propaganda/ indoctrination system as well as terror to instill a totalitarian atmosphere in society (ibid.: 107, 116–17). The propaganda/ indoctrination system uses not only mass communications, notably radio and newspapers, but also face-to-face communication by thousands of speakers and agitators deployed by the party and such mass-member organisations as the regime’s youth and labour movements.

Like most other post-Arendt theorists of totalitarianism, Friedrich and Brzezinski did not examine the origins of totalitarian regimes. However, they identified mass democracy as among the ‘antecedent and concomitant conditions’ for totalitarianism, argued that totalitarian movements and ideologies are ‘perverted descendants’ of democratic parties and their party platforms, and emphasised the significance of modern technology for totalitarianism – pointing out that four of the syndrome’s six traits have a technological dimension (ibid.: 6–7, 11, 13).

Their description of the structure of totalitarian regimes was wide-ranging and showed some obvious similarities with Arendt’s analysis. In particular, Friedrich and Brzezinski considered the totalitarian absolutist leader to be a unique feature of the regime’s structure

1. possessing ‘more nearly absolute power than any previous type of political leader’;

2. embodying a unique form of leadership that involves a pseudo-religious or ‘pseudo-charismatic’ emotionalism and a mythical/ mystical identification of leader and led;

3. subordinating the regime’s political party to a wholly dependent status so that it is more the leader’s following than an organisation in its own right (ibid.: 25–6, 29).

However, they also acknowledged that the extensive role allotted to the party in a communist regime was a significant structural difference between commu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables, Figures and Exhibits

- Introduction

- 1. Theories of Non-Democratic Government

- 2. Types of Non-Democratic Regime

- 3. The Emergence of Military Dictatorships

- 4. The Emergence of Party Dictatorships

- 5. Consolidation, Legitimacy and Control

- 6. Degeneration into Personal Rule

- 7. Policies and Performance

- 8. Democratisation

- 9. Semi-Dictatorships and Semidemocracies

- Further Reading

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Non-Democratic Regimes by Paul Brooker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.