![]()

| The Study of Communication Disorders | 1 |

1.1 Why study communication disorders?

A capacity for linguistic communication is a unique achievement of human evolution. No other species has the repertoire of linguistic and cognitive skills that are the basis of human communication. It is by virtue of these skills that people are able to develop complex social structures within their lives. These structures are the basis of our ability to co-exist with others and, accordingly, are integral to our mental and physical well-being. Given the centrality of communication to our existence, it is unsurprising that impairment of this important capacity should have many adverse consequences including social isolation, vocational and economic disadvantage and psychological distress. The severity of these consequences warrants serious consideration of the communication disorders that give rise to them. This book will examine these disorders and the child and adult clients who develop them.

The reader should be in no doubt that there is a very real need for academic and clinical studies of communication disorders. The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists estimates that 2.5 million people in the UK have a communication disorder. Of this number, some 800,000 people have a disorder that is so severe that it is hard for anyone outside their immediate families to understand them. There is a high prevalence of communication disorders in children. Pinborough-Zimmerman et al. (2007) found the prevalence of communication disorder in 8-year-olds to be 63.4 per 1,000. In 2003, speech and language impairments accounted for 18.7 per cent of students aged 6 to 21 years who were receiving special education and related services in the US under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (US Department of Education, 2007). Speech and language impairments were the second largest disability category after specific learning disabilities. Communication disorders are an equally significant cause of disability amongst adults. Hirdes et al. (1993) examined the prevalence of communication disabilities among community-based and institutionalised Canadians. Among community-based individuals, the highest prevalences were found in subjects aged over 55 years with figures of 30 per 1,000 population and 42 per 1,000 population reported in subjects aged 75–84 years and 85+ years, respectively. The percentage of community-based individuals who were completely unable to make themselves understood when speaking to family and friends increased from 4.2 per cent to 7.0 per cent (family) and 10.4 per cent to 12.9 per cent (friends) in subjects between 55 years and 85+ years. Harasty and McCooey (1994) reviewed 22 studies which examined the prevalence of general communication impairment in adults. These investigators reported a range of prevalence figures from 0.8 per cent to 3.9 per cent.

Indicators of psychological distress and quality of life suggest that communication disorders are a significant burden for those who develop them. Hilari et al. (2010) report that at three months post stroke, 93 per cent of their subjects with aphasia experienced high psychological distress compared with only 50 per cent of stroke patients without aphasia. Manders et al. (2010) found that people with aphasia obtained significantly lower scores for quality of life measures compared with healthy controls and patients with brain lesions without neurogenic communication disorders. Plank et al. (2011) found a correlation between voice-related quality of life and physical and mental subscores on a general health-related quality of life questionnaire in 107 socially active people aged 65+ years. Nachtegaal et al. (2009) found that hearing status in young and middle-aged adults was negatively associated with higher distress, depression, somatisation and loneliness. There is also clear evidence that occupational and social disadvantage attends the development of communication disorders. Whitehouse et al. (2009) examined psychosocial outcomes in young adults with a childhood history of specific language impairment (SLI), pragmatic language impairment or high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Participants with a history of SLI were most likely to pursue vocational training and work in jobs that did not demand a high level of language or literacy ability. ASD subjects had more difficulty obtaining employment than other subjects. All groups struggled to establish social relationships. The mitigation of the psychological distress and social and occupational disadvantage that attends communication disorders is a further reason why these disorders should be given serious academic and clinical consideration.

The high prevalence of communication disorders in the population and the distress and disadvantage caused by these disorders would be reason enough to justify the study of communication disorders. Yet, there is another reason why these disorders should be examined, a reason that is of particular relevance to linguistics. The study of how communication skills can be disrupted in children and adults often provides investigators with important insights into the nature of these skills in so-called ‘normal’ individuals. Models of language processing in particular have been developed and revised as information is gleaned from the study of language-impaired subjects. The properties of the semantic system have been directly based on the findings of studies conducted in subjects with aphasia. For example, Warrington (1981a) reports evidence for the vulnerability of subordinate compared with superordinate information in the verbal comprehension of individuals with aphasia. This pattern of impairment, she argues, indicates that ‘the semantic representations of single words are hierarchical or ordered in their degree of specificity’ (Warrington, 1981a: 411). Warrington (1981b) also reported a significant impairment in the ability to read concrete words compared with abstract words in a patient with an acquired dyslexia. This concrete word reading deficit, she argues, ‘provides a further example of category specificity in the organization of the semantic systems subserving reading’ (Warrington, 1981b: 175). The study of certain language skills and deficits in subjects with aphasia and other clinical subjects (e.g. individuals with language impairment in the presence of dementia) is thus of direct relevance to the generation of theoretical models of language processing within linguistics itself.

1.2 Human communication: processes and breakdown

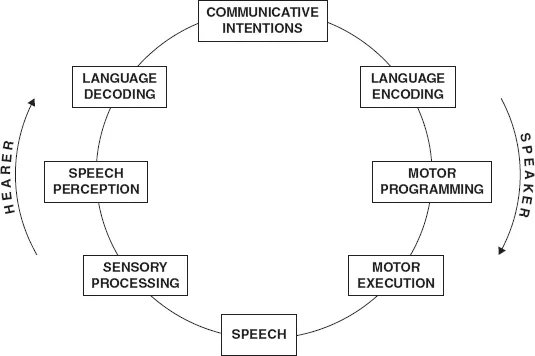

Human communication is a remarkably complex process that draws upon a diverse set of linguistic, cognitive and motor skills. Before we even utter a single word, we must decide what message we want to communicate to a listener or hearer. Deciding what that message should be is itself a complex process that requires knowledge on the part of the speaker of the context in which a verbal exchange is occurring, the relevance of the message to that context and the goals of a particular exchange. Having successfully made these assessments, the speaker will have a clear communicative intention in mind which he or she will wish to convey to the hearer. In most communication between people, that intention is conveyed through language, although it may also be conveyed through non-verbal means. To the extent that a linguistic utterance is to be produced, the speaker needs to select the phonological, syntactic and semantic structures that will give expression to this intention in a stage of the communication cycle called language encoding (see Figure 1.1). A linguistically encoded intention is an abstract structure that still has some way to go before it is in a form that can be communicated to a listener. The speaker must select from the range of motor activities that the human speech mechanism is capable of performing those that are necessary to achieve the transmission of the utterance to a listener (one need only think of all the non-speech, oral movements and vegetative movements that the articulators are capable of performing to see that this is the case). It is during the stage of motor programming that these selections are made (subconsciously, of course) and certain motor routines are planned in relation to the utterance. Motor programmes can only be realised if anatomical structures (e.g. lips, tongue, vocal folds) receive nervous signals instructing them to perform particular movements. These movements are carried out during a stage in communication called motor execution. Assuming all preceding stages have been performed competently, the result of these various processes is audible, intelligible speech.

Thus far, we have only described the processes that lead to the production of a linguistic utterance. Yet, human communication is not just about producing utterances but receiving or understanding them also. The first step in this receptive part of the communication cycle is called sensory processing. This is the stage during which sound waves are converted in the ear from mechanical vibrations into nervous impulses which are then carried to the auditory centres in the brain. The auditory centres are responsible for recognising or perceiving these impulses as speech sounds on the one hand or non-speech (environmental) sounds on the other hand (e.g. the bark of a dog). Having recognised certain speech sounds, the task of attributing significance or meaning to them within the utterance begins. By most accounts, rules begin to analyse the phonological, syntactic and semantic structures in the linguistic utterance in a stage called language decoding. Amongst other things, these rules tell the hearer the grammatical constructions used in the utterance (e.g. passive voice rather than active voice), as well as the semantic roles at play in the utterance (e.g. if a particular noun phrase is the agent in the sentence). The outcome of linguistic decoding of the utterance is not necessarily the particular communicative intention that the speaker intended to convey by way of producing the utterance (only sometimes is the literal meaning of the utterance the meaning that the speaker intended to convey). Quite often, further processing that is pragmatic in nature is needed to recover the particular intention that the speaker intended to communicate. Once that intention is recovered, for example, that the speaker who utters ‘Can you open the window?’ is requesting that the window be opened, only then is the communication cycle complete and the speaker’s intended meaning manifest to the hearer.

Figure 1.1 The human communication cycle

The complex nature of the human communication cycle means that there is a multitude of ways in which this cycle may be disrupted in people with communication disorders. The adult with schizophrenia who has thought disorder may have difficulty formulating an appropriate communicative intention, that is, one which is relevant, fulfils the goals of a particular communicative exchange, and so on. The adult with non-fluent aphasia has impaired language encoding skills, one consequence of which is the use of syntactically reduced utterances. The child or adult with verbal dyspraxia may struggle to select specific motor routines during the motor programming of the utterance. The child with cerebral palsy or the adult who sustains a traumatic brain injury may both experience dysarthria, a disorder that disrupts the execution of speech on account of failure of nervous impulse transmission to the articulatory musculature. Sensory processing of the speech signal may be disrupted in the individual with hearing loss. This loss may be either congenital (present from the time of birth) or acquired (as a result of an infection, for example) and may be conductive or sensorineural in nature. The child with Landau–Kleffner syndrome, who experiences language impairment in the presence of a seizure disorder, has intact hearing but is unable to recognise or perceive spoken words. The resulting auditory agnosia is often mistaken for deafness. The child with SLI and the adult with Down syndrome and intellectual disability or learning disabilities lack the language decoding skills required to understand the syntactic and semantic structures in the utterances spoken by others. Finally, the child with an ASD may have impaired pragmatic skills and may fail to recover a speaker’s communicative intention in producing an utterance. These conditions and many others not mentioned here (stammering, dysphonia, etc.) form the complex array of communication disorders that will be examined in this book.

1.3 Significant clinical distinctions

The discussion of the communication cycle in section 1.2 introduced a number of terms that are central to the study of communication disorders. The cycle drew a distinction between the expression or production of utterances on the one hand and the reception or understanding of utterances on the other hand. This distinction pervades the assessment and treatment of communication disorders. For example, the clinician who is asking a client with aphasia to point to the picture in which ‘The man who is crossing the road is tall’ is assessing that client’s understanding of relative clauses. The child with Down syndrome who is asked to describe a picture in which ‘The ball is on top of the box’ is having an aspect of his or her expressive syntax (viz., use of locative prepositions) assessed. Similarly, the clinician who is using exercises designed to eliminate the phonological processes of stopping (e.g. [tup] for ‘soup’) and fronting (e.g. [tat] for ‘cat’) in the speech of a 5-year-old child is working on expressive phonology, while the clinician who is asking the adult with dementia to organ-ise pictures according to semantic fields is focusing on an aspect of receptive semantics in therapy. The receptive–expressive distinction allows clinicians to characterise a number of different scenarios. One such scenario is where there is a mismatch in receptive and expressive skills in a client, that is, where one set of skills is significantly better than the other. For example, in the adult with non-fluent aphasia receptive language skills are typically superior to expressive language skills. Another scenario is where one set of language skills deteriorates more rapidly than the other in a client. For example, in the child with Landau– Kleffner syndrome receptive language skills are first to be affected. Expressive deficits usually occur later in the disorder and are thus considered to be secondary to the receptive impairment (Honbolygó et al., 2006).

A second important clinical distinction is that between a developmental and an acquired communication disorder. For a significant number of children, speech and language skills are not acquired normally during the developmental period. This may be the result of an anatomical defect or neurological trauma sustained before, during or after birth. The impact of these events on the development of speech and language skills varies considerably across the babies and children who are affected by them. The group of developmental communication disorders is thus a large and diverse one including children with cleft lip and palate (anatomical defect in the pre-natal period), with brain damage due to birth anoxia (neurological insult in the peri-natal period) or with cerebral palsy as a result of meningitis contracted at 6 months of age (neurological damage in the post-natal period). The group of acquired communication disorders is equally large and diverse. Previously intact speech and language skills can become disrupted for a range of reasons including the onset of disease, trauma or injury affecting the anatomical and neurological structures that are integral to communication. An adult may develop a neurodegenerative condition like motor neurone disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease (PD) or Alzheimer’s disease. He or she may sustain a head injury in a road traffic accident, violent assault, sports accident or as a result of a trip or fall. A previously healthy adult may have a stroke (known as a ‘cerebrovascular accident’ – CVA). He or she may succumb to infection (e.g. meningitis) or develop benign and malignant lesions on any of the anatomical structures involved in speech production (e.g. larynx, tongue). Any one of these events will disrupt communication skills, leading to disorders such as acquired aphasia and dysarthria.

A third distinction that is integral to the study of communication disorders is that between a speech disorder and a language disorder. These are not the same thing notwithstanding everyday usage (people tend to use ‘speech disorder’ to refer to both speech and language disorders). The distinction between a speech and a language disorder can be best demonstrated by referring to the diagram of the communication cycle in Figure 1.1. Breakdown in the boxes in this diagram labelled lang...