![]()

1

Bernard Mizeki

c. 1861-1896

The First Anglican African Martyr

In October 1958, Jean Farrant was approached by the Information Board of the Anglican Diocese of Mashonaland in what was then called Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The board asked her to write a modest sized pamphlet that could be distributed with a map to aid pilgrims who came annually to the Bernard Mizeki Shrine at Theydon, a site near Marandellas, which is itself located about an hour east of the Zimbabwe capital, Harare. Ms. Farrant took on this task reluctantly because, apart from being an Anglican herself and living in this district, she knew little about Bernard Mizeki. The assignment came at a delicate moment in the Christian, as well as political, history of southern Africa. The authority of the British colonial rulers was beginning to crumble, and the signs of rising African nationalism were unmistakable.

Upon setting to work, Farrant soon found much more material about the last ten years of Mizeki’s life than she could have imagined. But she was stymied in her quest for information about Mizeki’s early years. Then in an unexpected response to one last random request for information, she was directed to a small book, published in German in 1898, by a P. D. von Blomberg, of which the only known copies were housed at the British Museum and the Africana collection of the South African Public Library. Once translated, it turned out that this volume’s author was Paula Dorothea von Blomberg, a missionary in Cape Town, South Africa, who had conducted a school for Africans during the 1880s. It also turned out that Fräulein von Blomberg had identified Bernard Mizeki as her “most-loved pupil” and that she had recorded many heretofore unknown details about his early life. With this unexpected assistance, Farrant could record Mizeki’s life in considerable detail, which she proceeded to do in a book called Mashonaland Martyr, published in 1966 by Oxford University Press in Cape Town.

But the Mizeki story also witnessed several other unexpected turns after the publication of Farrant’s compelling biography. Those turns concerned the great transformation of political life in Southern Rhodesia that took place from the 1960s and even more the extraordinary transformation of Christianity in this same part of the world over the same time. For this later part of the Mizeki story, the distinguished historian of world Christianity Dana Robert provided a discerning update in 2006. She shows that Bernard Mizeki’s life is not only instructive for what happened while he was alive but also for how his memory has continued to be a living presence. A final introductory word is to note that the fragile quality of sources about Mizeki’s life illustrates some of the problems faced in reconstructing the early history of Christianity in areas that have recently become heartlands of the faith.

Early Life and Education

Mamiyeri Mizeka Gwambe was born in Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique), probably in the year 1861. His childhood seems to have been an ordinary one for the early days of European colonial expansion on the continent, since the boy was raised in traditional African fashion but also worked for a time in a trader’s store where he learned a little Portuguese. Sometime between the ages of ten and fifteen, he left the place of his birth with a cousin who convinced the young Mamiyeri to go with him to Cape Town, South Africa. In that rapidly expanding city, which anchored the British empire in Africa’s southern cone, the lad found a new name, “Barns,” and a variety of jobs—on the docks, as a house servant, as a gardener. He also avoided common vices like the intemperance that beset many who came from the countryside into Africa’s growing cities. In 1885 or shortly before, Barns made the connections that changed his life and that would influence the course of African Christianity more generally: he was introduced to the Cowley Fathers, and he entered a night school taught by Fräulein von Blomberg. The Cowley Fathers was the informal name of the Society of St. John the Evangelist, a religious order of high-church Anglicans founded in the Oxford district of Cowley in 1865. It carried out its mission—to promote spiritual growth and education—in several cities of the British Empire during that empire’s rapid expansion in the second half of the nineteenth century. In Cape Town the Cowley Fathers linked their work to the school run by the Fräulein.

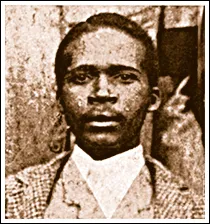

Barns soon became a favorite of the Fathers and at school because of his conscientious demeanor, but even more because of his intense interest in the Scriptures. On March 7, 1886, he was baptized along with six other young Africans. At the baptism he received the name “Bernard Mizeki.” It was the feast day of Saint Perpetua, who about the year 203 at Carthage had become one of Africa’s first Christian martyrs. Almost immediately thereafter, Bernard and several others asked the Cowley Fathers to train them as mission helpers. The baptismal photo that has been preserved shows him as short, square of face and with a determined countenance. He was then about twenty-five years old.

For the next five years Bernard attended Zonnebloem College, an institution that taught white, black, and colored (mixed-race) men and boys together. He assisted the Fräulein at her evening school and remained in close touch with the Cowley Fathers. Europeans found him shy, diffident and not particularly quick on the uptake. Yet over time they gave him an increasing range of duties assisting with various Anglican enterprises, which he fulfilled with honesty and efficiency. When Fräulein von Blomberg took him along on outings to villages, she discovered that he could be a warm and effective speaker. Only toward the end of his training did Mizeki’s intellectual paralysis in the presence of Europeans begin to give way; later the Cowley Fathers would look back and recall that Bernard’s gentleness had made the gospel message particularly attractive to other Africans.

Into Mashonaland

In January 1891, Mizeki met George Wyndham Hamilton Knight-Bruce, the newly appointed bishop of the recently created Anglican diocese of Mashonaland. Knight-Bruce, an earnest and enthusiastic young graduate of Eton and Oxford, had been the Bishop of Bloemfontein in South Africa. Now he was recruiting native helpers for his new diocese, which he had already explored on a long and arduous journey by foot.

As the control of the British Empire spread inland from the African coasts, so too did the Anglican Church. Elsewhere in southern Africa, missionaries had preceded empire, which led to conflict between the churches and the empire when colonial administrations arrived. In Mashonaland, where empire and church moved into African territory together, the problems were created by how native peoples responded to the incursion of church and empire.

Mashonaland, the region of the Shona people, lay in the north of what is now Zimbabwe, a landlocked region between the Zambezi River to the north and the Munyati River to the south that includes Zimbabwe’s capital city of Harare, which was known as Salisbury during Mizeki’s years. Earlier in the nineteenth century the Shona had been brutally conquered by the Ndebele people, but now both Shona and Ndebele were coming under the sway of the British, in particular the British South African Company of Cecil Rhodes. As part of “the scramble for Africa,” Rhodes and the company’s directors hoped to organize trading, mining and settlement in order to enrich themselves and bring civilization to the Africans. Bishop Knight-Bruce spoke out strongly against the political decisions that put Mashonaland under Rhodes’s control, but there was little he could do to hold back the tide of empire.

In April 1891, Bishop Knight-Bruce sailed with Mizeki and one other lay catechist from Cape Town to a port in Mozambique, from where they trekked westwards overland, carrying their own loads into the twenty thousand square miles of Mashonaland. The Africans went with the bishop as he met various subchiefs and sought suitable venues for their work. Mizeki eventually settled in a territory known as Theydon. It was controlled by Chief Mangwende, who lived in stone buildings abandoned by Portuguese traders. For the bishop’s gift of three pieces of calico and a few strings of beads, the chief allowed Mizeki to build a large mission hut near the chief’s imposing stone structure. That hut soon came to serve as church, school and dwelling. It was located on the banks of a river that supplied water for the garden Mizeki planted for growing his own food. He was on his own, sixty miles from the only other native catechist. For long stretches, his only outside visitor was Douglas Pelly, one of Bishop Knight-Bruce’s very few European colleagues. Dana Robert summarizes his situation in 1891 with these words: “Thus Bernard Mizeki, born in Mozambique, minimally educated in South Africa, and with little knowledge of either the Shona people or their language, was settled in the territory of Chief Mangwende.”

Missionary Mizeki

Almost immediately it became obvious that Mizeki had remarkable missionary gifts. Within a year he mastered the Shona language. Before he died, the student whose European teachers had worried about his intelligence became adept in eight different African languages, as well as English, Dutch and Portuguese. (He also acquired some French, Latin and Greek.)

Even more impressive than his linguistic ability were his practical talents, his amiability and his faithfulness. His garden was productive, he knew how to hunt and find firewood, and he showed his fondness for animal life by keeping three pet klipspringers (small antelopes). When smallpox threatened the region in 1895, Bernard administered vaccinations and so expanded the basic medical care he had been offering since coming to Mangwende’s territory.

As Mizeki mastered the Shona language, so too he grew close to the Shona people. Early on he won the friendship of Zandiparira, Mangwende’s head wife, who then served as his patroness in the community. Young children were drawn to him by his beautiful singing and by his willingness to teach them how to sing as well. Europeans who learned of his work sometimes complained that he wasted time on the Shona, who had a reputation for shiftlessness. But others were deeply impressed by how effectively Mizeki was reaching out through word, song and deed.

Day by day he said the Anglican daily offices of matins, prime, evensong and compline. He rose early to spend time reading the Scriptures and in prayer. And after catechumens had gathered to live around his mission hut, he began regular instruction in the basics of the Christian faith.

Mizeki taught the Shona that the deity they had known as Mwari—the creator God—was the Christian God and Father of Jesus. When locals warned him about the activity of other gods and spirits, who were thought to bring rain and control the unfolding of daily life, Mizeki insisted that it was Mwari, “our Father and Creator,” who caused the rain to fall and compassionately provided individuals and families with the means for sustaining life.

Mizeki’s first catechumen was John Kapuya, the son of a local nganga, a traditional diviner-healer. Bernard cared for this young man diligently, even to the point of finding a new place for him to live after members of his family and the ngangas began persecuting him. The first open convert was Chigwada Gawe, who took the name Joseph after he was baptized. Joseph’s young son was a special object of Bernard’s affection, although many observers remarked on his fondness for all children.

Bernard himself soon established a respected reputation as Umfundisi, the teacher. But he was also known as Mukiti, the celibate one, since in the face of local custom he remained single and chaste. After several years and much thought, however, he resolved to marry and took as his bride a young woman who had been an eager “hearer” at the missionary’s hut. She was Mutwa, who had been raised by one of Mangwende’s daughters after her own mother died. With this step, Mizeki entered into Mangwende’s own kin network, a move that not only spoke of his identification with this people but also led to bitter resentment among other members of Mangwende’s large family. The wedding took place in early 1896 and was performed by an African Anglican priest, Hezekiah Mtobi, who had only shortly before come to Mashonaland from Grahamstown, South Africa, as the first African cleric to join the Shona mission.

From his base in Mangwende’s territory, Mizeki journeyed on foot throughout the locality to preach the Christian message. He also contributed substantially to translation efforts under the direction of Bishop Bruce-Knight, for which he traveled regularly to the bishop’s home in Umtali. Bernard’s linguistic abilities made him a leader in efforts that soon resulted in Seshona translations of the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, the creed and other passages from the Bible.

Mizeki’s obvious talents drew the attention of colonial officials who from time to time asked him to serve as an official interpreter. It would have been easy for Mizeki to secure well-compensated employment as a translator in Umtali, but he chose to remain in Theydon. African catechists like Mizeki received only a sparse living allowance and occasional bits of cash for pocket money. His own catechumens reported that he remained entirely content.

After several years of labor Mizeki’s work prospered to the point that it was necessary to think about a new setting for the mission. After some deliberation and with Mangwende’s approval he decided to move his small community—several families and a number of small boys who had been entrusted to his care for education—across the river to a fertile site about two miles distant. The band of trees and the spring that marked this new location had a special significance, for it was considered a sacred grove inhabited by the spirits of the tribe’s ancestral lions. Locals worried about desecrating this sacred place, but Mizeki forged ahead as part of a systematic plan to reform what he saw as the evil practices of the Shona, including the killing of twin babies, habitual drunkenness, the offering of sacrifices to spirits and the harsh treatment (or murder) of individuals named by the ngangas as sorcerers. When Bernard was urged to make a small offering to the ancestral spirits before taking up his new place of residence, he instead drew the sign of the cross in the air and carved crosses in the trees at the edge of the sacred grove. Soon after moving, Mizeki felled some trees in the grove to make room for a field of wheat. This action would later be reported as sparking particularly strong resentment.

The End and a Beginning

Local hostility against Mizeki along with aftershocks from British imperial expansion created the forces that brought Mizeki’s promising mission to its fatal conclusion. In early 1896 the Shona were caught up in a rebellion, initiated by the Ndebele a few years earlier, against Cecil Rhodes’s British South African Company. Although the Ndebele were harsh oppressors of the Shona, the Ndebele resistance against British rule inspired the Shona. British leaders, including the Anglican missionaries, were surprised when the Shona joined in rebellion. But the Shona had also reacted to the new colonial order, with its hut tax, its mandated inoculations and its burning of infected cattle. In addition, the mid-1890s witnessed a tumultuous period of drought, locust plagues, new diseases for cattle and widespread famine that further poisoned relations between Africans and their new imperial rulers.

Locally, one of Mangwende’s many sons had taken particular offense at Mizeki’s entrance into the community, especially his marriage to one of Mangwende’s own grandchildren. This anger was fueled by several ngangas who, quite correctly, saw Mizeki’s new religion as an assault on their traditional worldview and the authority they had exercised in the local community. In mid-June 1896, messengers brought news to Mizeki’s local enemies that the Shona were attacking Europeans in nearby regions. This communication prompted a decision to go after Mizeki.

Shortly before, instructions had been sent to all Anglican catechists and teachers to gather for safety at a fortified mission farm. The message came from a member of Bishop Knight-Bruce’s staff, since the bishop himself was absent in England, where he would die later that same year from malaria contracted in Mashonaland. Mizeki hesitated when this message arrived, since he felt bound by Bishop Knight-Bruce’s earlier instructions to stay at Theydon. In addition, Mizeki had only recently given hospitality to an ill and incapacitated older man at the mission compound. Among the Shona it was a well-established cultural norm that the sick could be cared for only by family members; if Mizeki left this new patient, he knew that no one else would look after him.

The upshot was that Mizeki sent this reply: “Mangwende’s people are suffering. The Bishop has put me here and told me to remain. Until the Bishop returns, here I must stay. I cannot leave my people now in a time of such darkness.”

On Sunday, June 14, 1896, Bernard rang the mission bell for matins. No one came, not even Zandiparira, who had not missed a service in four years, nor those who were residing with Mizeki at the mission compound. Mutwa, his wife, had been told what was up: the local nganga was enraged; he had been informed by the spirits that Christianity was sorcery and Bernard was a sorcerer; for cutting down the sacred trees there was a sentence of death. Mutwa, who was pregnant, urged Mizeki to leave. He demurred.

On Wednesday evening, June 17, after taking in a stranger who arrived late and asked for lodging, Mizeki and Mutwa saw bonfires in the hills surrounding their residence. About midnight, Bernard answered a loud knocking at his door where someone announced that European troops had killed Mangwende. (They had not.) When Mizeki stepped outside, he was assaulted by three men, one of whom drove a spear deep into his side. Mutwa followed and threw herself on top of Bernard, but the men dragged her off and pitched her back into the hut. When she emerged, the men had gone and Mizeki seemed to be dead. Quickly she ran to find the wife of Chigwada Gawe (“Joseph”), who returned with her to the hut. M...