![]()

1 Introduction: Memory Failure and Its Causes

Michael W. Eysenck and David Groome

Introduction

Forgetting is arguably the most important and obvious feature of human memory. If the human memory system were capable of retaining all of its stored memories perfectly and permanently, there would be little to find out about the memory process. The fact that our memories often fail us is the most significant (and annoying!) feature of memory, and it is the main reason why the forgetting process needs to be investigated.

Although this book is concerned primarily with memory failure, it must inevitably deal with both memory and memory failure because they are two aspects of the same thing. However, our emphasis will be mostly on memory failure, because it is from studying the failure of memory that we can best find out how memory works.

Forgetting is basically a failure of memory. However, we can only say something has been forgotten if we had actually stored it in our memory in the first place. Bearing this in mind, Endel Tulving (1974, p. 74) defined forgetting as ‘The inability to recall something now that could be recalled on an earlier occasion'. We think that this is an acceptable definition, and it has the advantage of keeping things simple.

Memory is generally regarded as having three main stages (Kohler, 1947), which are as follows:

Input (Encoding) – Storage (Maintenance) – Output (Retrieval)

Forgetting occurs at the storage and output stages, but arguably not during input. If an item was not properly learned and encoded at the input stage, then the inability to retrieve it at some later point in time is not really caused by forgetting, but by a failure to learn it in the first place. Forgetting can therefore involve a failure of the storage process or a failure of retrieval. In practice, however, most forgetting in healthy people is probably caused by retrieval failure. This issue is discussed in more detail later in this chapter. The memory storage system seems to be fairly robust. However, it can fail when the brain suffers some kind of damage, as in the case of organic amnesia. (Forgetting resulting from organic amnesia is discussed by Melissa Duff and Neal Cohen in Chapter 7 of this book.)

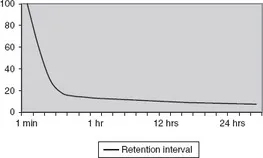

People have long been aware that they tend to forget things as time goes by. Ebbinghaus (1885) carried out the first truly scientific studies of memory performance, and he confirmed that forgetting appears to be time dependent, as shown in his well-known forgetting curve (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Forgetting Curve (Ebbinghaus, 1885)

The classic forgetting curve (as shown here) involves very rapid forgetting at first, but at longer retention intervals the rate of forgetting levels off. Ebbinghaus (1885) used meaningless nonsense syllables in his research, and he adopted the dubious approach of having only one participant (himself). However, subsequent studies involving more appropriate numbers of participants have confirmed the same general shape of forgetting curve for many other types of test material. In a review of more than one hundred years of research on forgetting, Rubin and Wenzel (1996) reviewed no fewer than 210 studies which confirmed the same basic forgetting curve for a wide range of different test materials.

However, matters are not necessarily that simple. More recent studies have shown that repeated testing of the same material with the same participants sometimes shows no decline in memory performance over time (Erdelyi & Becker, 1974; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006). In some cases, memory actually improves with time if tested repeatedly. Some test items may be recalled in a later test session which could not be recalled earlier (a phenomenon known as ‘reminiscence'), and in some cases there may actually be an overall improvement in memory performance over time (known as ‘hypermnesia'). In these cases, it would appear that some of the memories that seemed to have been forgotten had not actually been lost from storage, but had just become temporarily inaccessible.

One possible explanation for the above findings is that there may be a limit on how much we can retrieve at one moment in time, thus causing a temporary bottleneck in the retrieval system which will subsequently pass. Alternatively, it is possible that some form of inhibitory mechanism may have suppressed the item for a short time, the effect of which will subsequently diminish.

Another possible explanation for forgetting is that the human brain lacks the ability to remember huge numbers of memories, and that is the main reason for forgetting. However, that claim is debatable. It has been estimated that the human brain has approximately 80–90 billion neurons (Azevedo et al., 2009). If only 10% of those neurons were used to store memories, then hypothetically we might be able to store one billion individual memories (Richards & Frankland, 2017).

Regardless of the explanation, the occurrence of reminiscence and hypermnesia is consistent with the view that memory loss is often caused by retrieval failure rather than the complete loss of the forgotten item from the memory store. These studies also demonstrate that memory is greatly enhanced by repeated testing and retrieval, the so-called ‘testing effect’ which was mentioned earlier. There are many explanations of why repeated testing benefits long-term memory. However, the most plausible explanation is probably the one provided by Rickard and Pan's (2018) dual memory theory. According to this theory, testing often leads to the creation of a second memory trace that is stored along with the first memory trace that was formed during initial study or learning. The original memory trace is thus improved by the act of testing it.

Common Assumptions about Memory

Before considering the main theoretical explanations for forgetting, it is useful to discuss some of the popular or common assumptions about memory. Many of these assumptions are incorrect. We start with the work of Simons and Chabris (2011), who were interested in the general public's views on the nature of human memory, and in comparing those views against those of memory experts.

In response to the statement ‘Human memory works like a video camera, accurately recording the events we see and hear so that we can review and inspect them later’ (Simons & Chabris, 2011), 63% of the public agreed, compared to 0% of experts on memory. In response to the statement ‘Once you have experienced an event and formed a memory of it, that memory does not change’ (p. 3), 48% of the public agreed, compared to 0% of experts.

Similar findings were reported by Akhtar et al. (2018a), who considered the beliefs held about memory by members of the general public, police officers, and memory experts. Most members of the general public and the police officers believed that memories are like videos, and that accuracy of memory retrieval is determined by the number of details recalled and their vividness. In contrast, memory experts argued that memories are typically fragmentary rather than video-like and that the number of details recalled and their nature does not predict their accuracy.

Are Memories Permanent?

Another popular view about human memory is that information is stored permanently in long-term memory even if it cannot be retrieved. That view is consistent with the beliefs that memory is like a video camera and that memories do not change over time. Loftus and Loftus (1980, p. 410) asked psychologists and non-psychologists to decide which of two statements more accurately reflected their views:

- Everything we learn is permanently stored in the mind, although sometimes particular details are not accessible. With hypnosis, or other special techniques, these inaccessible details could eventually be recovered.

- Some details that we learn may be permanently lost from our memory. Such details would never be able to be recovered by hypnosis, or any other special technique, because these details are simply no longer there.

Loftus and Loftus found that 84% of psychologists and 69% of non-psychologists endorsed the first statement, thus indicating very clear majority support for the permanent memory hypothesis.

We can re-phrase the issue here by distinguishing between the availability and accessibility of memories (Tulving & Pearlstone, 1966). Memories are accessible if we are able to retrieve them, whereas they are inaccessible if we are unable to retrieve them. Memories are available if they are stored within the memory system, whereas they are unavailable if they are no longer stored. The notion of permanent memory implies that memories that are inaccessible are nevertheless available. According to this notion, no memories are both inaccessible and unavailable.

What does the evidence indicate? There is overwhelming evidence that many memories that appear inaccessible are nevertheless available within the memory system. For example, Tulving and Pearlstone (1966) used a condition where participants were presented with 48 words, with each word belonging to a different category. At the time of learning, each word was preceded by its category name (e.g. Weapons – Cannon). Some participants were given a test of non-cued or free recall: they were simply instructed to recall as many of the 48 words as possible. On average, they recalled 15 words, so that 33 of the list words were inaccessible.

Much of this inaccessibility occurred despite the relevant memory traces being available. Other participants were given a test of cued recall in which all of the category names were presented and their task was to recall the member of each category that had been presented initially. These participants recalled an average of 35 words. Thus, Tulving and Pearlstone (1966) showed that approximately 60% of words that were inaccessible on the non-cued recall test were nevertheless available in memory.

It has been claimed that the use of hypnosis lends credibility to the permanent memory notion by greatly increasing memory retrieval. However, the evidence is unconvincing. Hypnosis typically increases the amount of correct information recalled, but it also increases the amount of incorrect information recalled (Eisen et al., 2002). Thus, hypnosis merely increases rememberers’ willingness to report information (correct and incorrect). When Whitehouse et al. (2005) restricted the amount of information rememberers were permitted to produce in response to each memory question, there was no beneficial effect of hypnosis on recall.

Penfield (1958) reported findings that have often been interpreted as providing strong evidence for the permanent memory hypothesis. He applied low-intensity electrical brain stimulation to the neocortex of epileptic patients while they were awake during neurosurgery. Such stimulation apparently produced amazingly detailed memories: ‘Past experience, when it is recalled electrically, seems to be complete including all the things of which an individual was aware at the time’ (Penfield & Perot, 1963: 689).

Subsequent research using low-intensity electrical brain stimulation has consistently failed to replicate Penfield's findings. Curot et al. (2017) reviewed eighty years of literature. Electrical brain stimulation produced reminiscences (involuntary recall of memories) on only approximately 0.5% of occasions, and vivid personal memories were recalled only very rarely.

What can we conclude? It is virtually impossible to rule out the permanent memory hypothesis because we cannot prove with certainty that an inaccessible memory has actually disappeared from the memory system. However, it is definitely the case that no convincing evidence supporting the hypothesis has been produced to date. It is important to note that there are many reasons why memory traces might be available but inaccessible. Several theories that address this issue are discussed briefly in this chapter and at more length in the other chapters of this book.

Is Forgetting Always Undesirable?

Since the public's view is that our memories are accurate and unchanging over time, it is perhaps no surprise that most people agree that having a good memory is highly desirable. Is it true, however, that forgetting things is highly undesirable? It is clearly true sometimes. You have probably had the chastening experience of introducing people to each other when you realise with a sinking feeling that you have forgotten someone's name. Another distressing experience is to have arranged to meet up with a friend but you then forget all about it.

In spite of many negative consequences of forgetting, there can also be a negative side to remembering everything perfectly. Consider the famous Russian mnemonist Solomon Shereshevskii (often referred to as S.). He had exceptional memory powers (e.g. remembering lists of over 100 digits perfectly several years after learning). Ironically, his memory powers were so strong that they were very disruptive. For example, when hearing a prose passage, he complained, ‘Each word calls up images, they collide with one another, and the result is chaos'. The adverse effects of his incredible memory precluded him from leading a normal life and he finished up in an asylum.

More evidence that an absence of forgetting can be disadvantageous comes from the study of individuals who can apparently recall almost everything they have ever experienced in vivid detail, a condition known as ‘Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory’ (HSAM). This condition may seem desirable if you are one of those individuals who sometimes finds it hard to recall clearly important events from your own life. However, consider the case of Jill Price, an American woman, who is one of the best-known individuals with HSAM. She regards her phenomenal autobiographical memory as a problem: ‘I call it a burden. I run my entire life through my head every day and it drives me crazy!!!’ (Parker et al., 2006).

Surprisingly, Jill Price (and most other individuals with HSAM) exhibit only average performance on standard laboratory memory tasks. The explanation of her HSAM is that she has many symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder and spe...