- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Supervising work that takes place outside your view is a challenge, as is making the best use of the supervision you receive.This guide aims to help both supervisors and supervisees use supervision to maximise learning, and to support best practice.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Accountability Supervision and Clinical Supervision

Contents

- Two kinds of oversight 2

- Accountability supervision and clinical supervision 3

- Maintaining the distinction 5

- Your experience of supervision 8

- Accountability supervision and clinical supervision combined 13

- Management versus supervision 15

There are two kinds of supervision …

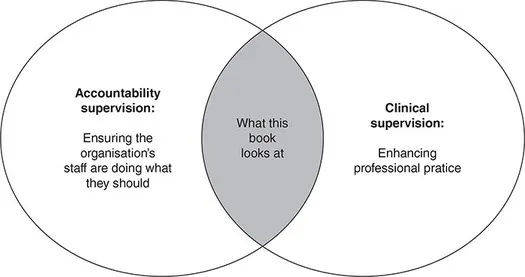

Well, actually that’s not true. There are dozens of different kinds of supervision, depending on the personal, professional and organisational relationship between the supervisor and the supervisee, the organisation where it is taking place, the issue being discussed, the skills, personalities, training, beliefs and cultural assumptions of those involved etc. etc. However, there is a fundamental two-way split that runs through supervision, which it is important to be clear about from the start. I will call the two sides of this split accountability supervision and clinical supervision. This book is about supervision in contexts where both are necessary.

Two kinds of oversight

The term ‘supervision’ comes from words of Latin origin meaning ‘over’ and ‘sight’. Supervision is oversight.

But there are different kinds of oversight. If you asked someone who worked in a factory what her ‘supervisor’ did, she might say something like ‘it’s someone who checks up on me and makes sure I’m doing my job properly’. If you asked a psychotherapist in private practice what her ‘supervisor’ did, she might say ‘it’s someone I reflect on my work with, someone who helps me disentangle my own feelings and history from those of my clients, someone I can brainstorm ideas with’.

The factory worker is talking about accountability supervision, which you’d expect to find in any organisation in some form or another (for how otherwise would organisations know whether their staff were doing what they were supposed to do?). It’s a form of supervision that is about making sure that staff pull their weight and act appropriately, that guidelines are followed, targets met, appropriate guidance and training are provided and that problems with delivering the service are identified. The supervisor is overseeing the work of staff on behalf of the organisation.

The therapist, on the other hand, is talking about clinical supervision. Her supervisor is not her boss, is not ‘above’ her in a hierarchy, but a fellow-psychotherapist who the psychotherapist herself perhaps pays to provide this service, or perhaps receives from her on a reciprocal basis. What this kind of supervisor provides is distance, perspective, a second opinion. The supervisor isn’t as emotionally involved as the therapist is and this means that, while there are many things about the therapist’s clients she can’t see (for she only knows about the client through the therapist), there will be things she notices that the therapist misses, for sometimes the therapist, in the midst of all the details and powerful feelings, ‘won’t be able to see the wood for the trees’, or will find it hard to disentangle her own feelings from those of the client. So this kind of supervision is also oversight, but it is oversight from a position of relative detachment rather than from a higher position in a management hierarchy.

The factory worker may not need ‘clinical’ supervision in this sense, and the therapist in private practice does not need ‘accountability supervision’, but in social work agencies and similar human service organisations, both are essential (see Figure 1.1). So when we talk about good supervision, we are talking about a combination of both accountability and clinical supervision. If you look at the UK government’s ‘knowledge and skills statement for child and family practice supervisors’ (DfE, 2018) you will see that the eight headings listed include both managerial and professional forms of skill and knowledge.

Figure 1.1 Accountability and clinical supervision

Accountability supervision and clinical supervision

The reason we need both kinds of supervision in human service organisations, is that the work shares some of the characteristics of the work of a psychotherapist but not others. The similarities with the work of the psychotherapist are that the work is relationship-based, involves distressing material, and involves operating in conditions of uncertainty. The differences are that service users don’t have a choice, the organisation as a whole is accountable, and the organisation has to provide a service.

Let us briefly unpick these:

The need for clinical supervision

- Relationship-based work: The relationship between the professional and the client is absolutely central to the whole endeavour. It’s not like, say, the case of a garage mechanic, where it’s helpful, no doubt, for the mechanic to have a good relationship with his customers, but the relationship is largely irrelevant to his ability to fix cars, and makes no difference to what he does when he’s underneath the car with his tools. In social work, on the other hand, and in other human services, human interactions are the tools. But these tools are not like spanners. You can’t just pick them up and put them down, they change over time, and they’re affected by feelings.

- Distressing material: Human service professionals deal with things like child abuse, terminal illness, disability and dementia, and they must also deal with people who may be angry, hostile, grief-stricken, or mentally disturbed. Practitioners need to understand their own emotional responses if they are to be able to do their best for service users.

- Conditions of uncertainty: Human service workers do not usually operate in fields where there are simple, precise, technical answers. Their work takes place in what Donald Schön called ‘The swampy lowlands, where situations are confusing messes incapable of technical solution … [but also] usually involve problems of greatest human concern’ (Schön, 1983: 42). Practitioners’ decisions may have huge consequences for other people’s lives, but there is nevertheless no exact science to tell them what to do. Given the personal nature of the work, and the distressing emotions it stirs up (and the fact that the client’s experience may have parallels with our own), it is important that human service workers have access to a form of supervision that will help them to disentangle what is going on, before reaching decisions about what to do.

The need for accountability supervision

- Service users don’t have a choice: People can choose whether to go and see a psychotherapist, and can decide for themselves which therapist they want to see, but many of the clients of human service agencies have no choice but to work with professionals such as social workers, youth justice workers or community psychiatric nurses either because the professional is the only way of getting access to a service they need, or because there is some sort of legal requirement to do so. This places service users in a position where they have little power, and, in order to prevent misuses or abuses of that power, human service workers need to be accountable to someone other than themselves.

- The organisation as a whole is accountable: Human service workers are employed by organisations that are answerable to government and to the public. They can’t just do whatever they feel like doing, or even whatever they think is important. They have to deliver the service that the organisation is mandated to deliver. Managerial oversight is needed to ensure that this happens.

- The organisation has to provide a service: Human service organisations can’t determine their own workflow in the way that a therapist in private practice can, but have to offer a service to the whole community on the basis of need. They need to ensure that work is appropriately prioritised so that new work can be taken on, and that the time spent on each case is proportionate to that case’s needs relative to the other work that needs to be done. These are matters that can’t be determined by an individual practitioner, but require overview of workload of the team or work unit as a whole.

Bill McKitterick (2012: 23–4) speaks of ‘two opposing forces’, or two ‘clusters’ of forces. On one side is the ‘cluster of forces of administration, managerialism and performance’ and on the other the ‘cluster of professionalism, thoughtful practice and relationship-based practice’. And these, he says, ‘need to be reconciled in supervision as important, but essentially distinct sets of activities, allowing neither to dominate or crowd out the other. The real skill of the professional in this field, in both giving and receiving supervision, is to bring these forces together, using … [the managerial/accountability side] to help deliver [the professional/clinical side]’ (2012: 23. My italics).

Maintaining the distinction

A small survey of social workers carried out by Turner-Daly and Jack (2017: 41) found that one third of respondents ‘reported that supervision did not provide any opportunities for reflection, many of them indicating that meetings with their supervisors were exclusively focused on case management issues’. A study of supervision records by David Wilkins (2017), found that only a quarter of the records contained analysis (using the Department for Education’s definition of that term [2015]). There was, for instance, ‘little recorded attempt to explore why people might behave in certain ways or how different aspects of family life might interact to create or mitigate risk’ (2017: 1135–6). Wilkins et al. (2017) looked at transcripts of supervision sessions in a ‘children in need’ social work team. A common pattern they identified was that an initial ‘verbal deluge’ of detail about a case (Wilkins et al., 2017: 944) was followed by the supervisor identifying the ‘problem’ and providing a ‘solution’ with a ‘tendency for the advice to concern procedural actions such as completing paperwork or arranging a meeting’ (Wilkins et al., 2017: 946). These rapid jumps from a descriptive narrative, to a ‘problem’, and then to an administrative response to the problem, left little scope for exploring the issues raised by the case in a wider sense. ‘Case discussions often included references to risk but it was more common to find risks being “named” than discussed in-depth’ (Wilkins et al., 2017: 946):

For example, whilst the social worker would say if they were worried about substance misuse, we found no discussions that explored how the child experienced this, whether the risk related to the parent’s behaviour or directly to the substance or both, whether the risk resulted from the parent’s use of the substance or from their procurement (e.g. because drug dealers visit the home), or both and so on. (Wilkins et al., 2017: 946)

And there was little discussion of feelings:

Case discussions also tend not to include emotions, either of the worker or children and families. This is not to say managers were uncaring. In almost all recordings, managers ‘check in’ at the start, asking how the worker is, how they are coping with their work and so on. However, once the discussion focused on particular families, emotional references were largely absent … [T]here was only limited consideration of why the social worker felt a particular way or how their feelings might be impacting on their behaviour and decision-making. The most common references were to frustration or other negative affect caused by perceived parental ‘resistance’. (Wilkins et al., 2017: 946)

Among the extracts quoted from the transcripts, the following is particularly striking:

SW: It was referred by the midwife because of concerns about possible substance misuse, cannabis. I met with mum and started to ask how things were going and she was saying this and that but when he, the dad, when he left, she opened up on me.

M: Like what? DV?

SW: Not really. When she was younger, she was trafficked here, and pimped and raped and she had another pregnancy, but it didn’t make it, and the dad, the new partner, he knows nothing about this. So now, I’m like, what do I do, because I have all this information about mum that dad doesn’t know but it will have to go into the assessment so he’ll see it.

M: You’ll have to write two different assessments. Did this happen here or in Ireland?

SW: In Ireland I think.

M: So, not in our jurisdiction. I’m wondering if mum had a visa when she came here, if she was trafficked? (Wilkins et al., 2017: 946–7. Italics in original)

So here the social worker has described to the supervisor a really shocking and distressing thing that happened to a woman she is working with – she was trafficked, pimped and raped – and has also told the supervisor how this woman opened up about this when her partner left the room, thus placing considerable trust in the social worker. This, I imagine, would have been a powerful moment for the social worker. But, at least as quoted here, the supervisor’s responses are entirely administrative: (a) the supervisor says the social worker will have to write two different assessments, (b) the supervisor notes that the crimes against the client happened in another legal jurisdiction, (c) the supervisor asks whether the client had a visa when she was trafficked.

One might wonder why the supervisor sidestepped into these bureaucratic questions and away from the obvious emotional charge of this material, but the point I want to make here is that talking about feelings (the client’s and the social worker’s) really shouldn’t be an optional extra in a situation like this because, without considering feelings, it is impossible to think properly about the case at all. Feelings are as central to the job as are (say), the organs of the body or the circulatory system to a surgeon. The reason the social worker was involved in this case, remember, is that a midwife was concerned about the woman’s use of cannabis during pregnancy. It is feelings that make people choose to use drugs, feelings that can make it difficult for a parent to prioritise the needs of a child, feelings that make unresponsive parents difficult for children to grow up with. If supervisor and supervisee are to gain some understanding of what is going on for this woman – Why does she use cannabis? What does this tell us about her care of child? What is the likely impact on the child? – they need to consider the likely e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustration List

- Table List

- About the author

- Introduction The scope of this book

- 1 Accountability Supervision and Clinical Supervision

- 2 Components of supervision

- 3 Alternative Forms of Supervision

- 4 Power and Authority

- 5 Casework at Second Hand

- 6 Judgements of Solomon

- 7 Games We All Play

- 8 The Framework

- 9 Dealing with Problems

- 10 The Needs of the Supervisor

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Supervision by Chris Beckett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Psychotherapy Counselling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.