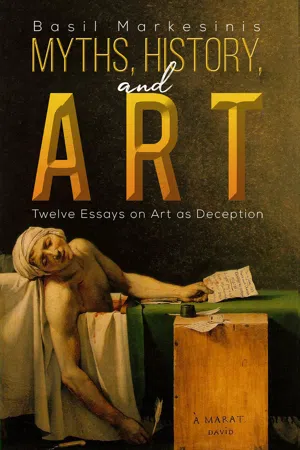

One of the most worrying characteristics of cruelty is the variety of forms it can take. All its shades produce undesirable results, though the effects can vary according to its type. In my view, the vilest forms are those related to political propaganda; throughout history, this has been confirmed by the propaganda produced by regimes which belong to the two ends of the political spectrum: communism or opportunistic socialism on the one hand and ideologies which can be bracketed under the generic term the extreme right. My opposition to such regimes is due partly to the fact that their ideas and deeds affect entire societies and partly because the socially adverse consequences of such ideologies tend to leave a long-lasting imprint. Art, which disguises human evil, is thus one of the most repulsive kinds, at any rate, once its viewers have managed to see what may lie behind artistic mastery. Jacques Louis David’s portrait of the assassinated Marat is one of the best illustrations of this.

i. Marat: The Real-Life Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Marat was an important figure of the French Revolution but not of the pivotal significance of Robespierre or Danton and this is because, essentially, he was a henchman. Henchmen of morally bankrupt and politically discredited regimes are abhorrent individuals. Arguably, they are often psychiatrically ill. Hitler’s Martin Bormann and Stalin’s Beria must surely fall into this category. Marat, who (according to Hippolyte Taine) once said that 270,000 heads had to roll before public tranquillity could be restored, placed himself in this category of paranoiac fanatics. His moral perversity was never explicable nor made pardonable, but to some of his contemporaries, it was hidden by the fact that he was exceptionally well-travelled and widely educated having studied at Saint Andrews and written works on politico-philosophical topics as well as medical topics as widely diverging as gonorrhoea and eye diseases. Constant travel to Bordeaux, Amsterdam and different parts of England among other places, earned him the admiration of such luminaries as Benjamin Franklin and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. By the eve of the Revolution, exceptional productivity – including a book on Newtonian optics and then a book on criminology (influenced by the work of the Italian Beccaria) – combined with a finely tuned sense of self-promotion helped him create quite a reputation for himself. For a time, he even managed to be hired as a physician in the household of the Count of Artois – later King of France under the name of Charles X. By the eve of the Revolution, a carefully planned ‘switch’ resulted in his being elected an Honorary Member of the Patriotic Societies of Carlisle, Berwick-upon-Tweed and Newcastle, and having repeatedly given scientific papers to Académie des Sciences of the Institut de France. What we see up to this point is a real Dr Jekyll; what, from now on, we were about to get was his other half – Mr Hyde.

The call for the Three Estates to be convened in May 1789 – something that had not happened since 1614 – marked the beginning of his involvement in politics. A series of pamphlets, published in quick succession, touched upon topics that preoccupied the Constituent Assembly or attacked the moderate reformers who were advocating some kind of imitation of the English constitutional settlement in order to save the French Crown. The more he spoke on these issues, the more he felt the need to create a medium through which he would publicise his increasingly extreme thoughts. So, in 1789, he founded a paper; after changing names twice, he finally settled on the famous (or infamous) title L’Ami du peuple. The paper was composed almost entirely by him, printed hurriedly and clandestinely distributed. What made L’Ami du peuple so dangerous was its growing practice of denouncing citizens for their disloyalty to the Revolution and treating them as guilty until somehow they managed to prove their innocence. By 1792, he had managed to become a Member of the National Convention, which declared in September that France was a Republic.

The publication of L’Ami du peuple stopped; its role, including the (often unsubstantiated) denunciations, was continued by a new paper entitled Journal de la république française. It needs no imagination to figure out that such antics soon earned him eponymous and anonymous enemies and forced him frequently to go into hiding. But his battle against the Girondins – the more moderate section of the revolutionary group, as contrasted with the ‘Jacobins’, the one he felt closer to – continued. As the date fixed by fate for his death approached, he became uncontrollably fanatic.

By now, however, Marat was also suffering from a skin disease, which began to develop around the end of the 1780s when he often took to hiding in the Paris sewers in order to avoid the growing number of enemies. We have a fairly detailed description of his symptoms – intense burning of his skin, itchiness, headaches, insomnia, insatiable thirst and a dermatosis (at times purulent and blistered) that apparently began in the anogenital areas and then spread over all his body – but no scientific diagnosis. Some, like Carlyle, suggested syphilis; others, in view of the constant thirst, thought it was diabetic candidiasis. None of these suggestions, however, explain the nature and duration of all the symptoms, something which led one medical doctor to suggest that Marat’s ailment would probably be diagnosed today as dermatitis herpetiformis. Whatever it was, it forced him to spend many hours a day in a bathtubfull of cold, medicated water. It was hereon the fateful day of July 13 1793, that Charlotte Corday, an unknown sympathiser of the Girondin cause, turned herself from an educated woman – well-versed in the works of Plutarch, Corneille (to whom she was distantly related) and Rousseau (as her last letter to her father attests) – into a cold-blooded murderess.

At first, it looked as if Mlle Corday’s attempt to reach her victim was destined to fail because she was stopped at the entrance of the building by the concierge, but she returned to her lodging, wrote some letters and then came back at around 7:30 that evening. Taking advantage of some other visitors, she mumbled to Marat’s common-law wife, Simone Evrard, that she had with her a list of agitators in Normandy which Citizen Marat would wish to see. He overheard this from his room and ordered that she be let in. His greed for more deaths thus hastened his own. Once inside, she found him in his bathtub. Marat grabbed the list from her hands and eagerly promised that they would all be guillotined. Within seconds, he had been butchered by the visitor. Marat did nothing more, though he is reputed to have cried out to his partner for help. Within four days, Corday was herself was tried and led to the guillotine, though not before, on her insistence, she had had her own portrait drawn by Jean Jacques Hauer. In those days, life was as cheap as the administration of justice could be quick. The brilliant, mercurial and amoral Madame de Staël would capture the significance of Marat’s death in one phrase when she wrote that he would be the one whom “posterity will perhaps remember in order to attach to one man the crimes of one epoch”.

This, however, was the man the Revolutionary Committee of the time was anxious to immortalise in a portrait and the artist chosen to do it was, indisputably, the most famous one in Paris at the time but also the greatest opportunist of an era which forced people to shift allegiances if they wished to remain alive. Jacques Louis David was his name; and his opportunism, apart from a brief spell in prison, allowed him to serve the directorate, Napoleon as consul, Napoleon as emperor and survive even the restoration of the monarchy in 1814 and then again in 1815, though this time he took the precaution of moving to Brussels where some ten years later he died a normal death.

ii. The Last Portrait: An Example of Art as Power

David’s portrait of Marat lying stabbed in his bath is a unique work of political spin and, at the same time, David’s, arguably, finest work of art. Some critics, like Anita Brookner, have seen it as a painting that (like others) reveals David’s psychic disturbances; others have insisted that it should be approached bearing in mind the turbulent socio-political context in which it was created.These are all issues that need not be addressed here, not least because their discussions by many authors have yielded no conclusive answers.

The official commissioning of the portrait presented the artist with a dilemma, which he had already faced in his past though never to the extent that it was presented to him in this case. In this and other paintings, David struggled to find an answer to an old dilemma: should art report the real or inspire through the ideal? Putting it more simply, in terms of artistic freedom, can freedom of expression explain or even justify the deformation of truth. One of the questions to be addressed was, and it remains, is to what extent did David’s work distort the truth? Giving in to this latter temptation would render the artist deceitful as well as his work. Yet, an objective understanding of the climate of that particular period in French history obliges us to admit that at the moment of his death Marat was being treated, by the revolutionaries at least, almost as a saint. To be sure, Marat was eventually also seen as the real Mr Hyde that he was; but, as stated, there had also been a time when, to the eyes of many, he had also been seen as Dr Jekyll, talented, respectable – and to some at least even in our times – considered to be, at the very least, an intriguing personality.

David may have been carried away by one image and thus, neglected to notice the second. He, himself, displaying the vanity of artists (and politicians responding to ‘the call to the office’), immodestly described how he felt the call of the people asking him to immortalise Marat’s death. Vain as he was, he did respond, but to achieve the ‘miracle’ he was asked to perform, he first had to recast his subject from a decomposing body into an idealised form. This was not easy for at the time of Marat’s assassination Paris was experiencing a heat wave and thus arranging his decaying body in a presentable form posed many difficulties. David did quite a lot to change the scene of the crime. No one has given a better blow-by-blow account of this transformation than Simon Schama in one of his most fascinating books. Readers who enjoy his style as much as his wide learning will do well to read his account to which I am indebted. Here, more dryly but more appropriately for the purposes of the text of a series of lectures, is the list of alterations made by David in order to convey a political message and not simply to depict a gruesome scene.

Marat’s body was, as stated, in a state of serious decomposition. It thus had to be heavily whitened in the painting and his flesh depicted as if made of imperishable marble;

Corday struck him near his clavicle and severed his carotid artery, but his wound is depicted as a neat incision at about the height where the Roman soldier’s lance pierced Jesus’ body. The aim of this change was clearly to invite comparisons.

Rigour mortis meant that it was impossible to close Marat’s eyes completely by the time the first sketches were done – hence that hooded look;

The letter stained with blood and held in his hand contains not the list of names denounced to him by Corday but a completely made-up sentence ‘it is enough that I am truly miserable for me to have a right to your benevolence’. This shows Marat as the victim of his own generosity rather than the rabid traitor-hunter he actually was;

A second letter on his makeshift desk – also a symbol of his simple tombstone – is a ‘thank you’ letter from a widow of a Republican soldier who has been granted a pension by the ‘good’ Marat;

His tongue ligature had to be severed in order to prevent it from lolling out of his mouth;

The hanging arm, pen in hand, was meant to show Marat working for the people up until the very end; in fact, rigour mortis meant that they could not move it in the right position, so an arm from another body had to be temporarily attached to Marat’s body; and finally,

On the floor, the good pen is contrasted to the ‘bad’ knife; the handle of the knife, which was apparently made of black ebony, is now white ivory in order to make the contrast with red blood even more obvious.

The result is what contemporaries described as the ‘pietà of the Revolution’; and in Schama’s concludingwords: “Despite everything it stands for, despite its place in the history of great lies, it remains shockingly, lethally beautiful.”