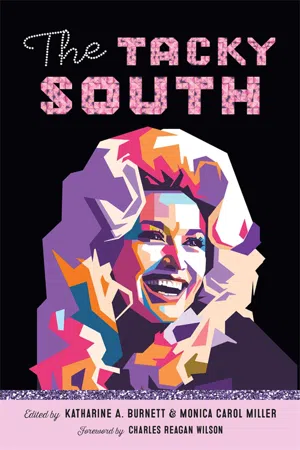

![]()

I.

Policing Tackiness

![]()

PICTURING THE TACKY

POOR WHITE SOUTHERNERS IN

GILDED AGE PERIODICALS

JOLENE HUBBS

Judgments about what—or who—is tacky mark out class boundaries that masquerade as aesthetic differences. In his now-classic study Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Pierre Bourdieu observes that “in matters of taste, more than anywhere else, all determination is negation; and tastes are perhaps first and foremost distastes” (49). “Tacky” is a term that, first and foremost, registers distaste. Today, the word disparages people as gaudy or dowdy, or finds fault with their shoddy or tawdry possessions. In the closing decades of the nineteenth century, “tacky” (or sometimes “tackey”) operated both as an adjective and as a noun designating “a poor white of the Southern States from Virginia to Georgia” (“Tacky,” def. A.2). By using the term as a taste-critiquing adjective as well as a class-defining noun, Americans bolstered associations between poor people and poor taste—and, as I work to prove in the pages that follow, those associations persisted even after the noun form fell out of use. Literary critic Jon Cook writes that “the exercise of taste is constantly drawing and redrawing the boundaries between and within classes” (100). Exercising taste by censuring tackiness engages in this boundary-making work, forging and fortifying differences between poor white southerners and better-off Americans.

This essay works to make the case that classism is written into the word “tacky.” To trace out how ideas about what is “dowdy, shabby; in poor taste, cheap, vulgar” came to be bound up with negative stereotypes about poor white southerners, I explore what this term signified and how it circulated in the late nineteenth century, concentrating on its appearances in the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, one of the Gilded Age’s most influential and august periodicals (“Tacky,” def. B). In stories and essays representing life in the South—and in the illustrations that sometimes accompanied them—the Century and other magazines appealed to their middle- and upper-class subscribers by presenting tackiness (as identity and as aesthetic) as the inverse of readers’ own tastefulness.

THE ORIGINS OF TACKY

Telling the story of the interlinked emergence of “tacky” as a noun and as an adjective means calling into question the Oxford English Dictionary’s etymology for the word’s adjectival form. The OED traces the use of the term to mean dowdy, shabby, or in poor taste to the diary that Kate Stone, the eldest daughter in a family of Louisiana planters, kept during the Civil War. In a journal entry dated February 16, 1862, Stone describes the arrival of “a weary, bedraggled, tacky-looking set” of visitors at her home (89). But this manuscript’s history casts doubt on this date for this word. The journal was first published in 1955 as Brokenburn: The Journal of Kate Stone, 1861–1868, taking its name from the cotton plantation inhabited by the Stones at the start of the Civil War. Brokenburn was based on a copy of the journal that Stone made in 1900. In his preface to the 1955 edition, literary scholar John Q. Anderson suggests that Stone copied the diary into the two ledger books that served as his source text “without evident revision” (xv). Anderson does not explain what led him to believe that Stone did not revise the work, but he could not have come to this conclusion by comparing the 1860s original to the 1900 copy, because the original manuscript was lost before Anderson began editing the document that Stone produced in 1900.

Historians who have studied Brokenburn point to textual evidence of revisions made around the turn of the century. In the introduction she wrote for the 1995 reissue of Brokenburn, Drew Gilpin Faust suggests that Stone reworked her diary decades after first writing it. Faust draws attention to the text’s organization—that is, the narrative’s “crafted structure,” including its plotted “progress toward Kate’s ultimate enlightenment and mature satisfaction”—as evidence of revisions (xxxi). In her 2015 Presidential Address to the Louisiana Historical Association, Mary Farmer-Kaiser argued that Stone reworked her story at the turn of the twentieth century in an effort “to recast her history” in a way that flatteringly depicted “her own place in the changing world that surrounded her” (412). Farmer-Kaiser’s analysis underscores how Stone imaginatively resituates Brokenburn out of its actual geographic location—which was somewhat inland of the Mississippi River in a zone that the crème de la crème of planter elites “identified as the ‘Back Country’” (Farmer-Kaiser 400)—and into the river-hugging epicenter of northeastern Louisiana’s high society.

Even more suggestive than the neighbors Stone wished to seem closer to, though, are those she worked to distance herself from. In a short section called “In Retrospect” that she penned in 1900 as a preface to her journal, Stone delineates the class divides that structured southern society in the antebellum era. After opening with a few rose-tinted remembrances of some of the plantation’s inhabitants, including her family members and the African Americans they enslaved, she moves to Brokenburn’s less fondly recalled inhabitants: overseers: “The men were a coarse, uncultivated class, knowing little more than to read and write; brutified by their employment, they were considered by the South but little better than the Negroes they managed. Neither they nor their families were ever invited to any of the entertainments given by the planters, except some large function, such as a wedding given at the home of the employer. If they came, they did not expect to be introduced to the guests but were expected to amuse themselves watching the crowd. They visited only among themselves” (5). “In Retrospect” reveals Stone’s concerns as she reviewed—and, I join Faust and Farmer-Kaiser in believing, reworked—her decades-old journal. This passage lays bare Stone’s interest in emphasizing the antebellum order’s stark social divisions. Entwining classism with racism through her simultaneous denigration of overseers and enslaved people, she distances both populations from planters. Painting overseers as “coarse, uncultivated,” “brutified,” and socially ostracized, Stone nostalgically invokes a bygone era when nonslaveholding whites sought little more than the pleasure of “watching” wealthier white people enjoy themselves.

The Civil War reversed the direction of this socioeconomically salient sightline. In the southern literary tradition, antebellum poor whites routinely figure as members of an unseen audience staring in awe at planters; in addition to Stone’s wedding watchers, we might think of young Thomas Sutpen in William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! (1936), who would “creep up among the tangled shrubbery of the lawn and lie hidden” there in order to watch a planter lounge in a hammock (184). Starting after the Civil War and reaching a crescendo in the 1880s, by contrast, current and former elites trained their eyes on poor white people. With former elites abashed at the figures they cut in their reduced circumstances and up-and-comers still working to accrue cultural capital to supplement their financial capital—and finding themselves sneered at as parvenus while they did1—both populations turned from performing their own tastefulness to scrutinizing poor people for signs of their tackiness.

Because Stone’s original diary has been lost—and because the first extant version of the text shows signs of being a 1900 revision of an 1860s original—dating Stone’s description of “weary, bedraggled, tacky-looking” travelers to 1862 (as the OED does) is a questionable decision (89). Setting aside this doubtful date for the adjectival form of the word clears the way for proposing that the two meanings of “tacky” emerged simultaneously and might be interrelated. In the 1880s, I want to suggest, “tacky” began to be used as a noun describing poor white southerners and as an adjective describing people who are “dowdy, shabby; in poor taste”: that is, people who manifest tastes associated with poor whites (“Tacky,” def. B).

E. W. KEMBLE’S TACKY TYPES

The tacky sprang to life in the pages of late-nineteenth-century American magazines, engendered by fiction writers (and a few essayists) and the illustrators whose drawings often accompanied their works. Writers and artists worked together in creating this figure. Artists read the stories they were illustrating before starting their drawings. Authors made requests about how characters would be depicted before illustrators went to work and afterwards, when, as artist E. W. Kemble explained about the process, “the drawings are sent to the author with a printed slip attached requesting the criticism of the writer upon the picture and changes are made accordingly.” This collaborative enterprise spawned a poor white archetype in which identity and aesthetics intertwine. Kemble’s caricatures of poor white southerners for the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine bear out Pierre Bourdieu’s contention that people at the bottom of the social hierarchy often “serve as a foil, a negative reference point, in relation to which all aesthetics define themselves, by successive negations” (50). The tacky, a poor person with poor taste, paraded before the Century’s middle- and upper-class readers as a counterpoint to their own aesthetic sensibilities.

Writer Joel Chandler Harris and illustrator E. W. Kemble worked together in 1887 to introduce readers of the Century to tackies living in Georgia’s piney woods.2 By the time of their collaboration, both men had published the works that would make them famous: Harris’s Uncle Remus tales and Kemble’s drawings for Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. After learning that Kemble–then a staff illustrator at the Century—had been assigned to illustrate “Azalia,” Harris asked Richard Watson Gilder, the magazine’s editor, to convey to the illustrator his suggestions for how to treat the story’s three character types. Harris asked Kemble to depict the tale’s “decent people” with “some refinement,” to portray Black characters with “some dignity,” and to avoid making “the Tackies too forlorn” (Harris, Life and Letters 228).

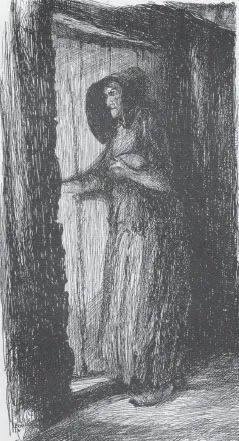

Both the protagonist and the third-person narrator of Harris’s local color tale work to define the characters termed tackies. Helen, the main character, labels them “picturesque” (547). The narrator calls them an “indescribable class of people” (“Azalia” 549). References to the tackies brim with superlatives—they are, for example, depicted as “steeped in poverty of the most desolate description and living the narrowest lives possible in this great Republic” (549). Both Helen and the narrator seem startled by the appearance of Emma Jane Stucky, a tacky woman Helen meets soon after arriving in Azalia. The narrator describes Emma Jane’s looks by first asserting that her “appearance showed the most abject poverty,” then making note of her “dirty sun-bonnet,” “frazzled and tangled” hair, “pale, unhealthy-looking face,” simple dress, and “pathetic and appalling” gaze (551). The first installment of this tale, which was published serially across three issues of the Century, ends with Helen declaring that Emma Jane’s appearance “will haunt me as long as I live” (552). Responding to her guest’s comments, the proprietor of the tavern where Helen is staying frames the poor white population as a segment of the region’s fauna that grows no less unsettling as it becomes more familiar: “I reckon maybe you ain’t used to seein’ piney-woods Tackies. Well, ma’am, you wait till you come to know ’em, and if you are in the habits of bein’ ha’nted by looks, you’ll be the wuss ha’nted mortal in this land” (552). Harris piques readers’ interest in seeing tackies, like Emma Jane, whose looks prove so disconcerting by closing the first episode of his tale with this commentary. The next installment of the story begins by reminding readers of Emma Jane’s haunting looks, because the text’s opening sentence describes her as moving “as noiselessly and as swiftly as a ghost” (712). In addition, this first page presents Kemble’s pen-and-ink drawing of Emma Jane (see Fig. 1).

Harris’s prose and Kemble’s picture establish the features that make Emma Jane dowdy and shabby—everything, that is, that makes her tacky. In Harris’s tale, Emma Jane seems dowdy in comparison to Helen. Emma Jane’s “appearance was uncouth and ungainly,” whereas Helen was always well turned out (551). Likewise, Emma Jane’s “mean” and “squalid” log cabin home (712) is a far cry from Helen’s Boston abode, in which the “easy-chair,” “draperies,” “bric-à-brac,” and other furnishings contribute to an “air of subdued luxury” (541). Kemble’s illustrations establish Emma Jane’s tackiness not only by contrasting her with posh, fashionable Helen but also by connecting her to other poor white women depicted as tacky. Kemble produced a number of illustrations for an 1891 Century essay about textile mill workers in Georgia. In preparation for illustrating this article, Kemble visited mill villages in Augusta, Macon, and Sparta, and in a letter to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution written after his drawings appeared in the Century, he insisted that the portraits were based on sketches of and notes about the workers he observed in Georgia. But the similarities between his 1891 Georgia cracker (see Fig. 2) and his 1887 Georgia tacky suggest that Kemble wasn’t seeing these mill workers with fresh eyes so much as he was reading them according to emerging types that influenced him and that he, in turn, influenced by systematizing and disseminating them through his prodigious artistic output.

FIG. 1. Kemble’s drawing of Emma Jane Stucky, a Georgia tacky. From Joel Chandler Harris, “Azalia,” Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Sept. 1887, p. 712.

Clare de Graffenried, the author of the 1891 essay in which this image appears, has a lot to say about the bad taste on display among the South’s poor white women. Declaring that “an unsuitable or grotesque fashion rules the hour,” de Graffenried enumerates the fashion faux pas of Georgia’s poor white population (490). Some mill women are tacky in the sense of dowdy, donning “that homeliest head-gear, the slat sun-bonnet” and a “style of dress [that] has not altered a seam in thirty years” (489). Other sartorial sins accrue to those who are tacky in the sense of cheap or vulgar. De Graffenried takes issue with inexpensive materials, including “cheap worsted goods” and “cheap lace” (489), as well as with garments that are “ill-made, ill-fitting, of cheap texture, and loaded with tawdry trimmings” (490).

FIG. 2. Kemble’s drawing of a Georgia cracker. From Clare de Graffenried, “The Georgia Cracker in the Cotton Mills,” Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Feb. 1891, p. 489.

De Graffenried’s commentary intertwines poor white women’s identities and aesthetics. She pours scorn on mill workers’ garish apparel while also imputing it to a congenital defect, explaining that their “inborn taste for color breaks out in flaring ribbons, variegated handkerchiefs, ...