![]()

1

THE AGE OF OVERSTATEMENT

Happy Hunty:…The field of usefulness

Is yearly narrowing with the advance

Of wealth and population on this coast.

There’s little left that any man can do

Without some other fellow stepping in And doing it as well. If one essay

To pick a pocket he is sure to feel

(With what disgust I need not say to you)

Another hand inserted in the same.

—Ambrose Bierce, “The Birth of the Rail,” Black Beetles in Amber, 1892

LATE AUGUST, 1878

Nîmes, Département du Gard, France

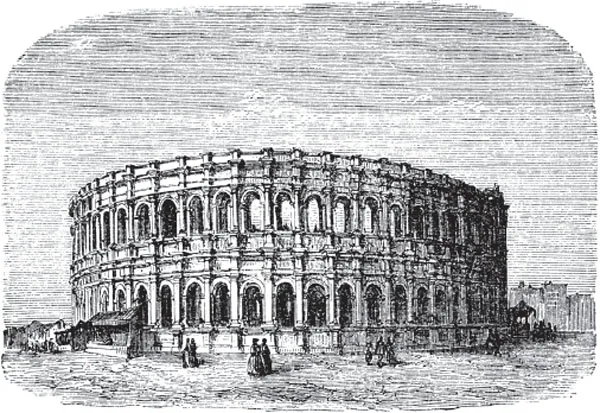

The Arena de Nîmes was a survivor but a deceptively intact one. It had been built by the Romans in the time of Vespasian, during the aftermath of civil war and chaos that had followed the suicide of Nero. Unlike its larger sibling in Rome—built during the same time and by the same emperor—the amphitheater at Nîmes had not collapsed. Yet over the centuries since the decline of the Romans, it had been repurposed many times into many things: a Visigoth fortress, a surround for a medieval palace and the location of an entire village.

The Arena de Nîmes, built contemporaneously with Rome’s Coliseum. From André Paul Émile Lefévre and R. Donald, The Wonders of Architecture, 1871.

All such past uses had been evicted by the time that three young men—Charles Follen McKim, Stanford White and Augustus Saint-Gaudens—explored its arched passages on a summer day in 1878. Fifteen years before, the amphitheater had been renovated—and perhaps that was too grand a word for it—into a bullfighting ring, for this was the Llenguadoc, sprawling between Provence and Spain and influenced much by the latter. Out went the remnants of the old village in the pit, and in its place, a semblance of the old Roman purpose was restored. Its great mass and its seeming preservation through the ages must have had a great appeal to the group, whose visit to Nîmes was—allegedly—for the purpose of soaking in the arts and architecture of rural, southern France. In fact, the journey had more the taste of a lark for the three young men.

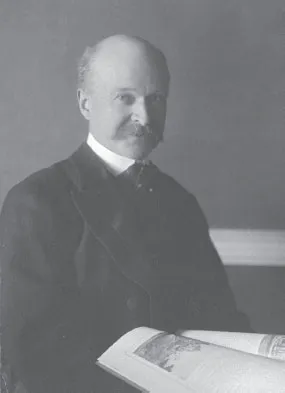

And they were young. McKim was but thirty-one, and the most established. He had been practicing architecture for a short six years, mostly designing beach homes for the socialites and minor rich of New York. Not all that much time had passed since he had been in France his first time, studying at the École des Beaux-Arts at Paris, learning his trade. Even now, though reserved and dour under the pressures of his New York life, there was still something of the charming schoolboy in him, the athlete who had no trouble publicly showing off his prowess on ice skates or with a baseball but who was too shy to give a speech or to be publicly praised. His hair, it was true, was rapidly thinning, but it was also still a shock of youthful red.9

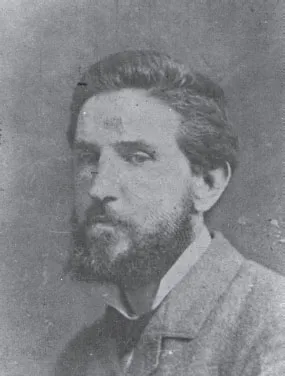

White and Saint-Gaudens— “Stan” and “Gus”—were also redheads and also young. Whereas McKim was an established, if middling, professional back home, Saint-Gaudens (thirty) and White (twenty-four) were both still working to establish their careers. They were then collaborating on their first project together, a monument to Admiral David Farragut, to be placed somewhere in New York. While the sculptor Saint-Gaudens had completed several commissions in the past, none had been this large or had held so much potential for public visibility. Wishing to work with only the best in sculpting, he had taken to a studio in Paris to begin the work.

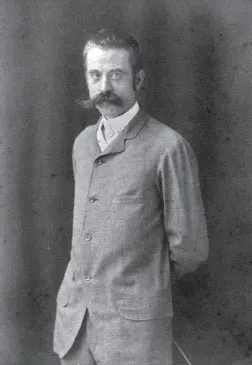

Charles Follen McKim is best known from portraits such as this one, taken later in his life. In 1878, however, he was still young, athletic and graceful and (although beginning to bald) had a shock of red hair. Frances Benjamin Johnston Collection, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ds-04713.

The 1878 summer party to Nîmes and back also included sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, seen here in a portrait made in Paris about that time. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-114885.

The youngest member of the Nîmes trio was Stanford White, who was then working with Saint-Gaudens and had not yet partnered with McKim. Library of Congress, LC-USZ61-1847.

Meanwhile, White—still bounding with a boyish enthusiasm—had few accomplishments to call his own. He did, however, possess an immense drawing talent. (At the tender age of eighteen, he had drawn the plans for Henry Hobson Richardson’s magnificent Trinity Church in Boston.) White was also the cause of this 1878 journey. With no formal education in architecture, and little experience of the world, White had scrimped and saved during his years as Richardson’s draftsman, building a nest egg earmarked for a trip to Europe—this trip. The only decision was when to go, and that was settled by an invitation from his friend Saint-Gaudens to collaborate on the Farragut during White’s planned sojourn.

Perhaps no incident quite sums up the youth of all three of these men than this visit to the Arena de Nîmes. There, the trio attempted to restage the distant past. McKim and Saint-Gaudens—perhaps less inclined to infantile enthusiasm and also curious to perform an acoustic experiment—sat at the top edge of the empty arena, which, during a bullfight, might have up to twenty thousand spectators. White related the event to his mother in a letter. “I went down (while McKim and St. Gaudens stayed on top) and rushed madly into the arena, struck an attitude, and commenced disclaiming.” McKim and Saint-Gaudens were able to hear White’s antic oration with exquisite clarity. Experiment concluded, White, ever the extrovert, playacted. He fought with “five or six gladiators”—all visible to him and him only. As he proudly reported to his mother, he slew his invisible enemies but then “rushed out with the guardian in hot pursuit.” Was this guardian a real caretaker of the 1878 arena or an ancient and imagined Praetorian guard? None now alive can tell.10

Dignity, as such anecdotes illustrate, was not always a strong suit among this trio, but then the trip itself had not been made for study so much as for escape. White’s bolt was from routine and from boredom, for in this first visit to Europe, he intended to soak in every aesthetic moment to the full. Saint-Gaudens, however, was fleeing his growing frustration with the Farragut. The situation had grown so bad that just days before, after a mocking critique by several students, Saint-Gaudens had carefully removed the plaster head of the statue and, setting it aside, tipped the torso and the troublesome legs onto the floor, shattering them. (This done, Saint-Gaudens had turned to McKim and White and stated “I’ll go to Hades with you fellows now.” Thus their journey to the south had begun.)11

Both McKim and White had worked for Henry Hobson Richardson, one of the most famous architects in the United States. From Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography, 1887.

For McKim, however, the trip was a diversion nested within the larger diversion that was his presence in Europe. His thriving architectural practice back home—with partners William Rutherford Mead and William Blake Bigelow—was in danger of collapse. Bigelow was McKim’s brother-in-law, and their relationship was good but now strained by scandal, as McKim’s wife, Annie, had filed for divorce. In the 1870s, the legal termination of marriages was a shocking and rare thing, and the couple—who had a three-year-old daughter between them—had not long been married. Several causes were at hand: financial problems in the Bigelow family in the wake of the Panic of 1873, a temperamental rift between the couple and even Annie’s stubborn preference for living in Newport, Rhode Island, to New York. All doubtless contributed. And Annie was spiteful, doing her best to spread rumors that McKim engaged in morally scandalous behavior, hoping to keep him from their daughter. If this was not enough to try McKim’s equilibrium, in May of the previous year his beloved sister Lucy had died, leaving behind a grieving husband and three now motherless children. McKim had spiraled into depression. His reputation and his livelihood were under threat, his sister was gone, his youth—like his hairline—fleeing. When White told him that he was headed to Europe, McKim decided to join him. A journey to Paris appealed more than it ever had, for it would be a journey back to a time and place where, for McKim, all had still been possible, to where he had felt young and happy.

For all three young misfits then—the frustrated bohemian Saint-Gaudens, the joyous and neophyte White, the melancholic and troubled McKim—this journey to Nîmes was a needed tonic before facing what the future might hold. The good wine and cheap food and pretty women; the lush, sun-burnished landscape of the Llenguadoc; the centuries-old churches, monasteries and manors: each was a balm to impending challenges and changes. Soon, Saint-Gaudens and White would have to return to Paris to advance the work on the Farragut. White, further, was scheduled to depart for Belgium in the autumn. Yet the person for whom the trip would end soonest was McKim, who was to return to New York in September to deal with his divorce and with the future of his business partnership. Playing at Romans in the Arena de Nîmes? It could not last.12

McKim’s beloved and departed sister Lucy—more properly Lucy McKim Garrison after her marriage—was one of several connections between Charles Follen McKim and Henry Villard. In 1865, Lucy had married Wendell Phillips Garrison, son of famous abolitionist leader and Bostonian William Lloyd Garrison. A little over a month later, Wendell’s sister, Fanny, had married the young journalist Villard. The two families—the Garrisons and the McKims—had been part of the same abolitionist circles for years, and Villard, as a liberal European and would-be man of letters, had been very active in those circles and become well known to both families.

Further, Villard had a hand in McKim’s choice of career—ironically by arguing against it. In 1867, McKim the boy had been contemplating a switch from mineral sciences to architecture and a trip to Europe to study the latter. His father, James Miller McKim, had written to Villard, asking his advice on the latter, given Villard’s familiarity with Europe. Villard had urged caution, noting the cost and complications of a move to Paris for someone so young (and who had recently made such a radical shift in plans). Instead, Villard had advised McKim to follow the standard practice of the day in architectural training: take on an apprenticeship at an American architectural firm. McKim did so, but it had not held. “In a few weeks it became evident that his heart was not in the work,” Miller McKim confided to Villard. As a result, McKim’s parents gave up all pretense of opposing his grand plans, and his father wrote again to Villard, asking for practical advice on where “Charley” should sleep and eat, how much he would need to live on and other particulars.13

James Miller McKim asked Villard for advice regarding his son Charles’s plans to study architecture in Paris. Villard had advised against the move. Massachusetts Historical Society 81.435.

Intriguingly, young “Charley” and Villard shared a few personality traits. Both were, for example, considered highly persuasive. Villard the journalist was a fine and convincing speaker, in a way that McKim’s recurrent stage fright would never allow, but McKim—who was known as “charming Charley” by his peers—was very effective on a personal level. His persistence and his earnest, measured expression of convictions often convinced shaky clients of the wisdom in his choices. Combined with an athletic grace and an understated couture, McKim did well within society when he wished to. His ugly divorce had revealed another quality that McKim shared with Villard: a view of Europe as a shelter from the problems of home. Both men would make multiple trips to the Old World, frequently under clouds of disgrace, shame or (perhaps feigned) illness. Europe was also, for both of them, the cultural standard by which America ought be judged and, with great personal effort, made more equal with.

Where the two differed was in starting place and direction. While McKim was an American wishing to bring some of Europe’s sophistication to home, the late 1870s saw Villard become the sophisticated European who was ever more drawn into American affairs. And European was the right word, for although Villard had been born into the Palatinate, he had shed his specifically Germanic ethnicity in favor of a more cosmopolitan European identity. The man born Ferdinand Heinrich Gustav Hilgard had, upon arrival in the United States, taken on an Anglo-American first name and a French last. At a time when relations between France and the United States were near their strongest, Villard’s choice allowed him to triangulate a position between his immigrant status and his new American culture. Yet Villard had always kept a foot in Europe and seemed to spend more time in hotels and spas and on board steamships and trains than in any fixed American home.

Yet as the late 1870s unfurled, Villard had been embroiled deeper and deeper into the affairs of the American railroads that the Frankfurt bond committee had sent him to investigate. Most worrying was that the accord he had reached between the bondholders and Ben Holladay had not held, and in 1876, he had been forced to return to Portland and completely oust Holladay from his transportation empire. In Holladay’s place, Villard had installed the only man he knew who could take on the job—himself. He began to make annual trips to Oregon—typically in late spring—while leaving the day-to-day work in the hands of the Portland-based Richard Koehler.

The management of the companies—the Oregon &a...