![]()

Chapter 1

MURDER ON THE HIGH SEAS

Failing to serve an arrest warrant for murder, Marshal William Peck of Rhode Island stated, “DeWolf could not by me be found.”21

James DeWolf of Bristol, Rhode Island, sailed from Africa to Havana, Cuba, in 1790 on his ship the Polly with a new load of slaves. As an experienced captain, DeWolf had knowledge of navigation, the possibilities of bad weather, the danger of encountering pirates and the potential for illness among the crew and the human cargo.22 Early on in the voyage, one of the slaves, a middle-aged woman, became ill with smallpox. DeWolf decided to quarantine her on the top deck, away from the rest of the slaves, to avoid infecting the ship’s population. To ensure that his crew was not exposed to her illness, DeWolf ordered that the slave be tied to a chair to keep her from wandering about. It has been speculated that there was not actually a chair on board but that perhaps the slave was sequestered to the crow’s nest, a basket or seat often made of webbing, usually with leg holes, attached to the top of the center mast of a vessel. Seamen used the crow’s nest to spot land or oncoming vessels. However, while a bird’s nest was hoisted up and down the center mast, rarely was it removable. It was reported that DeWolf noticed that the slave, still tied to some form of chair, had rapidly deteriorated. He then made the determination that she needed to be killed.23

Initially, DeWolf asked for a volunteer to carry out the task of murder, and according to a deposition from the court, the entire crew refused, telling him that they would have nothing to do with it.24 DeWolf then ordered a crew member to draw down a hoist with the grappling hook and assist him with the device. A gag was tied around the slave woman’s mouth to silence her and ensure that if she screamed for help, the other slaves below deck would not hear her.25 DeWolf then gave a new command to help him with the hoist. The hook was placed into the rope at the back of the chair, and the woman was lifted into the air. It was then that DeWolf swung her over the side of the ship, dropping her into the sea—alive. Toward the end of the deposition, crew members claimed that once DeWolf had dropped the woman into the sea, he stated how sorry he was to have lost such a good chair.26

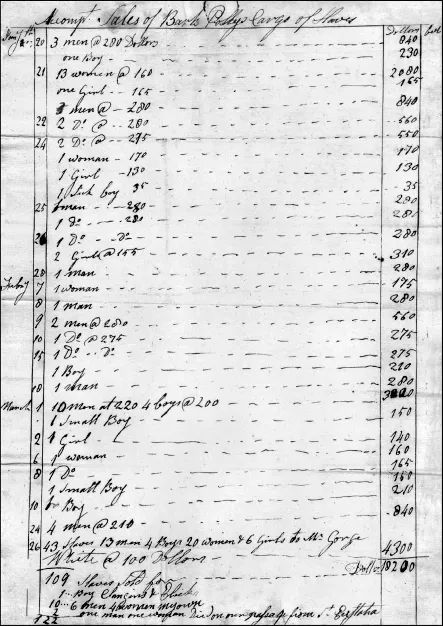

Once the voyage ended and the Polly returned to port in Rhode Island, DeWolf created his account of sales for his cargo of slaves. On it, he meticulously listed each slave and the price he had collected for them individually. At the bottom of his ledger, DeWolf noted that 109 slaves were sold for profit. Additionally, a boy was given to someone whose name is illegible. DeWolf personally kept 10 slaves, 1 male slave was infirm at the conclusion of the voyage and 1 female slave was noted to have died during the voyage. DeWolf clearly had no compulsion to hide the fact that, indeed, a death on the voyage had occurred.27

Simultaneously, after the Polly returned to Rhode Island, someone—it is not clear whom—reported the incident to the local authorities. However, it has been speculated that it was federally appointed customs collector from Newport William Ellery, as he had become acutely aware of DeWolf’s slaving practices and wanted desperately to see them end.28

As collector, William Ellery had a multitude of responsibilities, which included, among other things, upholding maritime laws, inspections of vessels as they arrived and departed, crew inspections, verification of insurance policies and measurements of all vessels to determine their tonnage. He was acutely aware of the guidelines of each slave law as it was implemented, and he maintained communication with the Department of Treasury in Washington, D.C., which saw that the laws were carried out for the president. As seen through a lifetime of correspondence, Ellery took his position as collector very seriously.29

Surprisingly, the persistent and law-abiding Ellery came from a similar family background as DeWolf. He grew up in a home where slaving constituted the family’s livelihood in the mid-eighteenth century. William Ellery Sr. was involved in the slave trade for years. However, his son and namesake came to abhor the trade and chose to follow a different route. He became an antislavery activist and was deeply involved in the political development of the early United States.

Slave ledger from the Polly. At the bottom, DeWolf noted that he kept ten slaves for himself and acknowledged the death of the female slave he threw overboard. Provided by Bristol Historical and Preservation Society.

Ellery was a representative of Rhode Island at the Continental Congress and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. In 1790, George Washington appointed him the collector for the customhouse in Newport. Ellery remained in the position of collector until his death in 1820 at the age of ninety-two. He exhibited extraordinary determination as he fulfilled the duties of collector, struggling through many political differences with several administrations, as well as with the DeWolf family.

At the first session of the federal grand jury in Rhode Island on June 15, 1791, a court deposition was taken from two of DeWolf’s crew members from the Polly. Thomas Gorton and Jonathon Cranston recounted what they saw regarding the plight of the African woman.30

According to the deposition taken from the two crewmen, the woman suffering from smallpox was brought above deck and tied to a chair by both DeWolf and Gorton. The crewmen stated that she received some water to drink, with the crew paying only marginal attention to her for fear of contracting this highly infectious disease. After two days of being tied to a chair and exposed to the elements, it was noted that she became increasingly ill, according to both Gorton’s and Cranston’s accounts. Captain DeWolf called his crew together and determined that the slave needed to be thrown overboard in order to protect not only his valuable slave cargo but also everyone on the ship. He made no effort to help her first. The deposition concluded with the following summary of DeWolf’s alleged crime:

[DeWolf] not having the fear of God before his eyes, but being moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil…did feloniously, willfully and of his malice aforethought, with his hands clinch and seize in and upon the body of said Negro woman…and did push, cast and throw her from out of said vessel into the Sea and waters of the Ocean, whereby and whereupon she then and there instantly sank, drowned and died.31

Abolitionist sentiment had risen in the years following the American Revolution. Rhode Island’s Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784, which was written to stop both slavers and slaveholders from exhibiting a cruel and blatant disregard for human beings, attacked the attitude that slaves were just property. Both the Federal Slave Trade Act of 1784, which declared that no American should be engaged in the slave trade, and the Rhode Island Act of 1787, which stated that no slave was to be imported into the state of Rhode Island, were broken by DeWolf.32

Moreover, in 1790, just prior to DeWolf’s offense, the first Federal Crimes Act had passed, making it a federal offense to commit murder or other crimes on the high seas. It gave jurisdiction to the federal courts to deal directly with violators of federal laws and included no exceptions for slaveholders or slave traders. DeWolf’s crime was recognized by the federal government as an act of piracy and murder on the high seas and, if he were found guilty through a trial by jury, was punishable by death. Although DeWolf never faced a trial on U.S. soil, if he had, he would have been charged, at the very minimum, with manslaughter. According to the Federal Act of 1790, manslaughter, too, was punishable by death, whether the act was committed on land or at sea, within the United States maritime boundaries or outside of them.33 Whether collector Ellery was involved in the Polly case, he would not have objected to DeWolf’s prosecution as a result of the deposition because DeWolf had positively broken the law, and Ellery was acutely aware of that fact.34

Slaves were considered by slave traders and slaveholders as chattel, pieces of personal or real property owned by individuals. Yet the willful killing of slaves was illegal. However, these crimes were rarely, if ever, prosecuted within the states because state legal codes provided exceptions that allowed slave owners to claim that the killing of the slave had been justified or accidental. Slave captains routinely ordered crew members to throw sick slaves overboard, almost as a matter of hygiene, to keep them from contaminating the cargo and, more importantly, the crew.35 Since captains often asserted that they had the right to end the life of a sick or rebellious slave, for some it remained difficult to understand why DeWolf was charged with murder. Nevertheless, the law remained on the side of the slave.

The federal grand jury in Rhode Island found DeWolf guilty and charged him with violation of a federal law. Attorney General John Jay, under the direction of President Washington, submitted the request for the arrest of DeWolf on the charge of murder. A warrant was then issued for DeWolf’s seizure. The deposition that justified the warrant was taken on Wednesday, June 15, 1791. The date of the warrant’s dissemination would have occurred between Thursday, June 16, and Friday, June 24, 1791. Although it had been less than ten days since the crew members gave their deposition, DeWolf could not be found. Shortly after the warrant was given to the marshal for DeWolf’s seizure, a brief article appeared in the Providence Gazette on June 25, 1791, that addressed DeWolf’s murder charge. It stated:

The Grand Jury found a bill against James DeWolf of Bristol, in this State, for the willful murder of a Negro Woman on a late [African] Guinea Voyage. There was not a trial on this bill as Capt. DeWolf had quitted [departed] the United States immediately after his arrival from the said voyage.36

A couple of months prior to DeWolf’s impending arrest, the deputy marshal of Rhode Island placed an announcement in the Newport Herald declaring that, on behalf of Rhode Island’s district court judge Henry Marchant and William Ellery, a warrant had been granted for a vessel from Bristol that broke the 1790 federal law. The vessel had been seized, and the captain and crew were set to go on trial for carrying onboard items for the sole purpose of participating in the purchasing and selling of slaves.37 The publication of such occurrences had become more prevalent in local newspapers, perhaps as an aggressive reminder that Ellery had the support of local and federal officials regarding enforcement of the law.

The first federally appointed local marshal, William Peck, reported to the Rhode Island federal court system semiannually that he continued to attempt to serve the arrest warrant for four years, from 1791 until 1795, but that he could not find DeWolf.38 Bristolian legend states that no one seemed to know where DeWolf had disappeared to during his four-year absence, or at least no one was willing to admit to knowledge of his whereabouts. How was legal justice so easily evaded? Who was James DeWolf, and how was he able to successfully orchestrate a system that allowed this to happen? Did DeWolf create the conditions that allowed him the freedom to not only commit murder but also to evade arrest? For the time being, DeWolf had managed to elude the authorities while he continued to build his family empire from afar. However, was Peck party to the murkiness regarding DeWolf’s whereabouts?

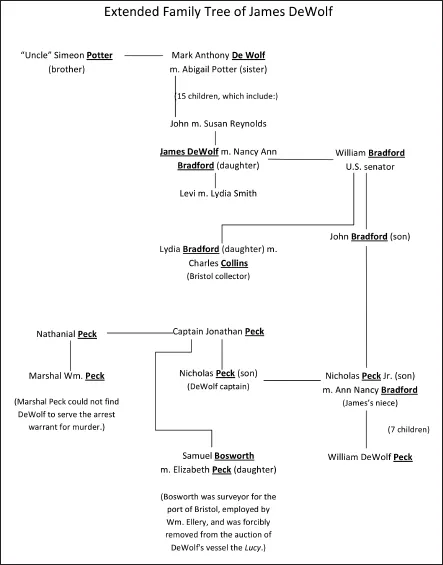

This is where the family trees of Bristolian residents begin to intertwine. It also alludes to the reason DeWolf was “never found.” Marshal Peck’s paternal uncle was a captain in the slave trade. Peck’s cousin by his paternal uncle, Elizabeth Peck, was married to Samuel Bosworth, who was under William Ellery’s employ as the local surveyor for the port of Bristol/Warren. Elizabeth’s brother Nicholas Peck was also a slave captain who had a son in the business. Nicholas’s son married Ann Bradford, the niece of Nancy Bradford DeWolf, who happened to be the wife of James DeWolf. Nicholas Jr. and Ann named their firstborn son William DeWolf Peck. Nicholas Jr. was also hired by DeWolf to captain his ship the Nancy, which originally carried ninety slaves onboard but delivered only seventy-five in Havana.39 The complicated family tree of DeWolf shows that he was related by marriage to both the marshal’s family and the family of the surveyor for the port of Bristol. Both men were keenly aware of the efficacious means of which DeWolf was capable.

A modified DeWolf family tree that shows his connections to the Bradford, Peck and Bosworth families. Table created for the author by Tim Clinton.

Since a slaver’s insurance covered the mortality of slaves at a predetermined percentage rate of anywhere between 5 to 25 percent, it was not uncommon for captains to throw overboard a mortally ill or deceased slave to protect the rest of the human cargo and crew from infection. Insurance policies written for slaving vessels stated that payment for the mortality of “black cargo” would not be honored unless the loss of a predetermined percentage of slaves had been documented.40 For example, an insurance policy established that a captain could collect on a policy if 25 percent of his cargo died. If a captain lost a small number of slaves to disease, it would not be cost effective for him to throw additional slaves overboard in order to file an insurance claim. Instead, the captain would take every precaution to maintain the health of the remainder of his cargo, as the sale of the slaves yielded a higher p...