![]()

CHAPTER 1—HOW THE TRUTH OF BATTLE IS FOUND

These combat narratives of the 7th Infantry Division in the Kwajalein campaign are the product of a simple process of unit interviews—after battle. Although they all tell of the Kwajalein fighting on the days from January 31 to February 5, 1944, the process through which they were written really developed out of the Makin operation of November, 1943.

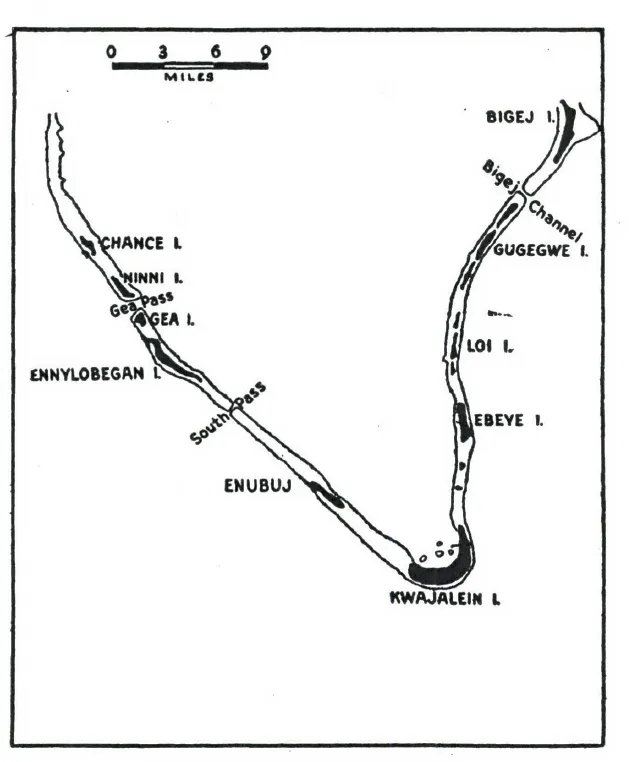

Situation as of D Day (January 31, 1944).

On the morning after the Makin “Fight on Sake Night,” as the 3d Battalion, 165th Infantry of the landing forces continued its advance to the head of Butaritari Island of the Makin group, we were already thinking of how to write the history of that battle. There was a general doubt that the tactical confusions of that strange night of combat would ever be clarified. Few of those who were closest to it, including the actual commanders in the battle, knew much more about it than that our men had behaved well in a difficult situation. None knew the relationship of any one combat episode to another. Even in these first hours after the fight we were already mixing up parts of the story, and as rumor got about over the island, fable was rapidly being substituted for fact.

Yet all of the actors were present, except the killed or badly wounded, and there had not been many of those. The one way to try for the full, detailed truth of battle was to muster the witnesses and see for once whether the small tactical fogs of war were as impenetrable as we had always imagined they were. Only by asking those who had done the fighting could we find out more about the fight.

So we began with the gun crews, talking this first time to each crew separately in the presence of their company officers and members of the battalion staff. For four days we went over and over that one night of battle, reconstituting it minute by minute from the memory of every officer and enlisted man who had taken an active part.

By the end of those four days, working several hours every day, we had discovered to our amazement that every fact of the fight was procurable—that the facts lay dormant in the minds of men and officers, waiting to be developed. It was like fitting together a jigsaw puzzle, a puzzle with no missing pieces but with so many curious and difficult twists and turns that only with care and patience could we make it into a single picture of combat.

We discovered other things as we went along—important things. We found that the memory of the average soldier is unusually vivid as to what he has personally heard, seen, felt and done in the battle. We found that he recognizes the dignity of an official inquiry where the one purpose is to find the truth of battle, and that he is not likely to exaggerate or to be unduly modest. We discovered also that he will respond best when his fellows are present, that the greater the number of witnesses present at the inquiry the more complete and accurate becomes the record, since the recollection of all present is a check on the memory of any one witness.

Thus in four days we were able to reconstruct the story of that Makin night defense which has been named “The Fight on Sake Night,” and we went on from that encouraging result to study other group actions in the Makin campaign. The lessons we learned in doing this continued to point plainly in one direction. If we were correct in our assumptions, then the proper way to reconstruct the experience of any one company or similar unit in battle was to assemble the whole unit and let every man be heard by all the others, his comrades in the fight.

Southeast portion of Kwajalein Atoll.

Accordingly, this was done for another island operation by the 7th Infantry Division (commanded by Major General Charles H. Corlett) after the Kwajalein battle. And in this book every reader can gain a clear idea of what the combat units found out about themselves.

The results will speak for themselves in the pages of history. For the word “confused” will never have to be used in speaking of any part of the ground force action on that Pacific island battlefield. What happened at Kwajalein is accurately and fully known, as this book indicates. Through the method of the interview after battle we have the explanation of everything that went wrong during the battle, every mistake, every confusion. We can, moreover, understand the essence of leadership and training in the many things that went right. And we can know what each platoon, what each company, actually did.

As we went ahead with the company interviews on Kwajalein in the 7th Division, we became more and more certain of the most important discovery of all—the immediate tactical value gained by seeking the full detailed history of an action. The companies themselves were direct and immediate beneficiaries of all that was learned. Their men had fought together on the same field and yet they did not understand what they had done. Until the interviews after battle brought it out in full, no real significance was attached to his personal role in the battle by the man in the ranks, simply because he had not been able to relate his part to anything else. The average company officer knew only as much of what had happened to his men in battle as what he had seen of them himself from moment to moment, or what had required some official attention from him at one time or another. No lieutenant commanding a platoon has ever more than a fraction of his small force in view at any one lime in combat.

We should have known all along that this was the case—that the truth of battle had never been known in full before. Soldiers have never in the past sat down and straightforwardly rebuilt the various parts of their collective experience, even after they have been in sudden death action as members of the same squad of no more than ten or twelve men. Inertia, and often reluctance, stops them from any private inquiry and they are not under any military requirement to do it. Thus the most valuable part of the lessons which can only be learned in bloodshed become lost to an army. Each personal experience is sharply etched against a vague and faulty concept of how things went with the group as a whole. The fighting men do not know the nature of the mistakes which they make together. And not knowing, they are deprived of the surest safeguard against making the same mistakes next time they are in battle.

Consider what happened to Company B, 184th Infantry, the true story of whose action in one day on Kwajalein is told in Chapter 4.

Until the company interview was held, well after the battle was over, the two rifle platoons did not know that they had attacked simultaneously toward each other from different sides of the same Jap-filled shelter. Or again, in Company F of the gad Infantry (Page 172) the men thought on the last day at Kwajalein, and continued to think until the interview brought out the truth, that they had been fired into from the rear by their own mortar section. Yet all the time the actual facts were right there in the company—facts which, put carefully together again, would have shown them that it was Jap fire they had received and not American.

Direct tactical and moral dividends of this type came out of every company interview held. One company officer after another said in similar words, as the interviews went on: “I am dumbfounded to learn that these things happened to my men.”

And these were first-class officers! They had commanded bravely and well in battle, though they had not previously known of any way to glean in full the tactical and moral combat lessons of their own fighting experiences.

Said the Commander of Company C, 17th Infantry: “In two days of this briefing I learned more about the character of my men and where the real force lies in my company than I had known in all the time I fought and trained with them.” That ought to be worth any amount of painstaking effort to take advantage of the company interview after combat.

Actually such interviews require comparatively little effort. The men like to do it. No other form of military education will sustain their interest for so long a period. To reconstruct one day of vigorous battle will usually take about two days of briefing (five to six hours each day), provided the men are given the opportunity to do most of the talking. They will always be keener and will participate more freely on the second day, and if a third day is needed the response will again rise.

The thing is done the most direct way. Battle starts for each Infantry outfit with an incident somewhere along the line and is carried on in other incidents. In other types of units—supporting mortar, machine-gun or Artillery units, for example—the beginning and progress of battle are similarly a sequence of incidents. It is never true that all men of an outfit fight at one time. And even in a sustained engagement hours long, a number of them will not be in the fighting at all.

It is best to find the starting point before briefing begins in earnest. Let one man get on his feet to tell what happened from the beginning of the fight as he remembers it. The reconstruction of the story will then take a natural course, provided only that the interviewing officer uses a little judgment and imagination in keeping to the thread of the narrative and introducing all pertinent lines of inquiry—clearing up each point fully as it comes up.

As the first man mentions the names of other living participants, they are each called on to tell what they know about the action at the point reached. They in turn will bring other men into the story. The order of the witnesses should depend upon the time sequence of the combat story and never upon the rank of those who are telling it. All soldiers including officers are equal in the informal court. All are simply looking for the truth for the good of the whole outfit—and other outfits. The interview after battle is not at all the time for officers to make pretensions to superior knowledge of the common experience—and few are disposed to try it. The success of the inquiry comes of their good judgment and good faith.

Let us illustrate the method a little more concretely by telling how we got started with Company B of the 184th Infantry, whose story forms the fourth chapter of this book. We had studied minutely the ground that had been fought for, and we had also acquired much more knowledge of how regimental and division headquarters and other units had reacted to Company B’s battle performance than was yet known to the officers of that company. In a ten-minute conference before the company was assembled, Lieutenants Harold D. Klatt and Frank D. Kaplan, who led the forward rifle platoons in the fighting, told us about the relationship of their two platoons and how they happened to become separated during the battle. They identified Sergeant Roland H. Hartl as one of the key figures.

Captain Charles A. White, the company commander of Company B who was recovering from a wound, was able to come out of the hospital to attend the company interview. When the session started, we asked him: “What could you see of our own supporting artillery fire when you jumped off?” He did not remember anything specifically about it. We then asked the whole outfit if anyone remembered and after a few opinions had been expressed the company agreed as a group on the distance the shells were kicking up ahead of them when the attack began. We then asked Captain White: “Were the tanks with you?” He answered: “No, they didn’t get up in time and we jumped off on time without them. I don’t know why they failed us.” That was put down as a question on which we would check with battalion and the tanks.

It was absolutely necessary in these interviews to use a blackboard, or, lacking one, some kind of surface on which events could be roughly pictured. We asked one sergeant from each platoon to come up and sketch in Company B’s ground with relation to the rest of the island. Sergeants Hartl and Floyd D. Eyerdam came forward. We then asked Lieutenant Klatt to describe the ground over which he advanced and we called on his platoon as a whole to supplement his description with any of the details which they remembered. This was repeated with the other platoon.

Then we came to the question: “Who was the first man to fire at an enemy during the advance?” Several named the same man and we asked him to get up and tell his story, which he did.

We asked the group as a whole: “How much fire was coming against you at this time?” Some ten or twelve men spoke on the point. We got into the real meat of the problem when Lieutenant Allen E. Butler made a general statement about how the two platoons, which were supposed to stay close abreast as they drove forward in the battle, split away from each other because of the difficulties of the ground. Then Lieutenants Klatt and Kaplan separately told of their local situations and the state of their information with respect to each other’s platoon. But we had to take it up with a number of men to learn just what had happened. Commanders of units do not—cannot—see the whole action.

Almost invariably the clearest statements came from the privates. We asked them not only what they did in the fight, but what they actually said and how they felt. They were usually quite sure of their recollections of their emotional reactions. But they rarely remembered just what they said in the midst of action. It was the man who heard another man say something who was most likely to remember the words, and not the man who said them.

Now none of this calls for an expert trained at length in such briefing, or for special training in conducting such interviews. Any company officer who has the respect of his men and a reasonable amount of horse sense can do it. If he is fitted to lead them in battle, he is fitted to lead them in re-living the battle experience. Frequently, after less than ten minutes of coaching, we placed a company commander in front of his own men and let him carry on for the next three days with only a minimum of help from the sidelines.

We found that invariably when a commander had such control over his men that he could hold their interest during the time required to reconstruct the story, the company...