![]()

PART ONE

Christ-Enlivened Student Affairs Staff

“What makes your student affairs practice Christian?” This was one of the questions that we asked our seventy interviewees. Here are the first lines of some responses:

- That’s a great question. [pause] Yeah, that’s a good question . . .

- That’s a tricky question.

- Your question is so good, because what makes it Christian [pause] I think [pause] is what [pause] . . .

- That’s a good question. I think [pause] it’s telling that I’m pausing here. [pause] I think it says a lot . . .

As is often the case, there is much said in the unsaid; we think the pauses of these interviewees speak volumes. These opening lines, the likes of which were surprisingly common, seemed to suggest that many Christian student affairs leaders (SALs) had not given much thought about how their faith identity might animate, inform, or shape their professional identity.

Fortunately, a host of additional riches lie in the previously unstudied thinking and practice of the professionals themselves. The collection of experiences, thoughts, and expertise we have the privilege of sharing has been honed by years of practice—countless conversations with students, conduct hearings, staff meetings, and certainly more than a few lessons learned the hard way.

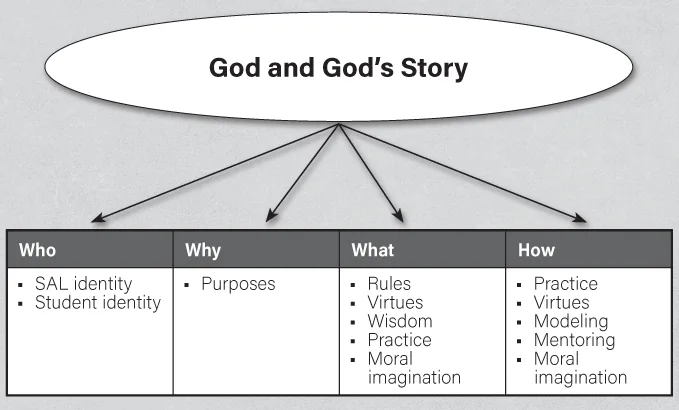

To organize what we found, we rely on a framework we use throughout the book that helps us classify the various responses we received and, ultimately, construct an appropriately complex picture of how Christ enlivens student affairs (see Figure I.1).

Figure I.1. The Christian Student Affairs Imagination

The model is structured around the basic questions included in any educational philosophy. Under an overarching animating narrative (the narrative of God and God’s story), we want to know who is doing the teaching and who SALs want their students to become, why SALs are doing what they do, what is the nature of the content that SALs attempt to impart, and how do SALs go about imparting it? Under each of these questions, we have included sub-elements that help construct the larger categories. For example, to better understand what SALs seek to impart, we need to know not only the rules and restrictions they impose, but also the virtues, wisdom, and moral imagination they seek to cultivate in their students and in themselves. This book explores this model at length because we believe it is not enough to merely know the means of carrying out student affairs practice. As SALs, we must also understand the who, why, and what that informs those means.

![]()

1

WHO ARE WE?

Understanding Our Christian and Professional Identities

If we don’t have a concept of who we are,

it’s really hard for us to care for others.

—Aubree

All that we do centers on first being the people

of God in order to do the work of God.

—Cindy

O ne of the most curious things about the New Testament epistles is how they begin. Paul and the other writers consistently seek to help early Christians understand who they are “in Christ” before they can realize how to act as Christians. Thus, the first parts of most epistles, such as Romans, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, do not contain commands. Instead, the opening chapters discuss the identity and work of God through Christ and our identity in light of this reality. Only later do the authors instruct us how to live in light of that identity. This approach is like what the Christian student affairs leaders (SALs) quoted above say. Before talking about the practical ways Christ animates student affairs, we want to take a similar approach in this chapter by first exploring who we are as both professionals and Christians.

Routes into the Profession

If we really want to get to know someone, we ask the person about their story. When my wife and I (Perry) were dating long-distance (she’s Canadian and we met in Russia), to get to know each other we shared cassette tapes on which we recounted to each other our life story up to that point. Narratives reveal an important core of who we are.

It helps to start at the beginning, so in order to understand the professional identity of our SAL interviewees, we asked them about how they became professionals. We heard a lot of stories like this one:

Growing up, people asked me what I wanted to do, and I would just say, “I want to help people.” I always kind of felt a little bit foolish that that was my answer, because it just wasn’t a profession, right? It was like, “I want to be a doctor. I want to be a teacher.” Whatever. But even as I got to college, my undergrad is in family psychology, and realized I didn’t want to go necessarily into counseling, per se, but I liked investing in the lives of people, supporting them, challenging them, pushing them to be better, walking with them in the highs and lows of life. Always have had a little bit of a pastoral bent toward me and so, yeah, somebody said to me, as a freshman, “I think you’d make a good RA.” I’m like, “You really think so?” So, I did that for three years and after . . . didn’t really have a certain job I wanted to do, so I applied to work as an admissions counselor at my alma mater. So, I did that for about a year and a half, almost two. Transitioned into residence life, was an RD, for five years.

Like the story above, more than half of our participants described their route as “unusual,” “circuitous,” or a “winding road.” Andrew, a vice president of student affairs, theorized about the route into Christian student affairs further: “It’s a funny path. I was just telling somebody yesterday, because I teach in our higher ed program at [institution]. And I often will tell our young professionals, ‘Everyone has a different path [into] this calling.’ I really do think it’s a calling to embrace. And so, I didn’t graduate from my undergrad with a student affairs degree. Nobody does.” To Andrew, the diverse routes into the field reflect the uniqueness of the calling. This calling, as Andrew noted, is not one that has a home during undergraduate education.

As a result, it is no wonder student affairs professionals come from a variety of different disciplinary backgrounds. As professionals described their training in our interviews, they referenced eleven different disciplines, ranging from “higher education” or “student affairs” to less related disciplines like a “master’s degree in exercise science” or “architecture.” Most interview participants had degrees related to student affairs/higher education (41 percent) or Christian education/ministry (34 percent).

The diversity of educational backgrounds is revealed in our larger survey. Though we did not ask survey participants to indicate the field of their degree, the degrees themselves and the institutions at which they were earned indicate a diversity of training. Most survey participants were working in Christian student affairs with either a bachelor’s degree (30 percent) or a master’s degree (49 percent). Seventy percent of these participants (working with a bachelor’s or master’s degree) received their degree from a faith-based institution. The next largest block of degrees were participants who were working with some form of a doctorate (13 percent). Of those with a doctorate, just under half (49 percent) were earned at a faith-based institution. A final point worth noting is the number of professionals with non-higher-education professional degrees—5 percent were trained in a seminary or divinity school and 2 percent were trained in a business school.

Motivations for Entry

Without a single pathway into student affairs, what does lead people to the field? Analysis of the interviews and survey responses revealed professionals were motivated to become SALs for a variety of altruistic, personal, and faith-based reasons. It should be noted that the categories are not mutually exclusive—many professionals mentioned reasons that fell into multiple categories.

First, when asked about what motivated them, the majority of SALs indicated they were motivated by the opportunity to develop students. One survey participant described Christian student affairs as “almost entirely focused on developing people.” Mary, a director of student engagement, articulated a similar purpose: “This is what it’s all about. It’s all about the students for me . . . to see them grow. . . . It’s very fulfilling.” For Mary, it was the opportunity to develop students that brought her role a sense of significance. Participants did not always use the word “development.”Others described Christian student affairs in the following ways: “bringing out the potential in people,” “for transformation,” “trying to mold . . . young men and women,” “identity formation,” or “cognitive development.” Matthew summed up these sentiments well: “I just find that to be a really ripe time to do some fun work with them about growth and identity and other stuff.” Regardless of the language used, a significant percentage of SALs were motivated by a desire to develop students.

Others focused less on the development of students and emphasized that it was a general desire to help others that motivated their work. Participants made statements like, “I knew I wanted to help others” or “I like helping people.” Others talked about a desire to work in the “helping professions,” a desire to “give back” or to “serve” subpopulations within higher education. Lisa fleshed out the motivation to help or serve others a bit more fully:

Within six months [of working in Christian student affairs], I realized, “Oh my goodness, this is my home. This is my profession. This is what I want to have as my career.” . . . In my undergrad, I was a communications major, public relations, advertising, and then business minor. I thought I was going into HR—something definitely serving people—but I thought I was going into human resources or a hospital or something. What I found is that I could use the desire to serve people, but I could serve college students. It’s a great mix to feel like I can be in the ministry but yet be in a profession that’s not traditionally in the church walls.

Here Lisa references her varied undergraduate degrees, her desire to work with people, and her desire to work in ministry. Her quote reflects many of the stories we heard in our interviews. Participants shared that they saw Christian student affairs as an opportunity to draw together the seemingly disparate strands of their backgrounds and beliefs into a single role.

Second, most participants indicated at least some of their motivation came from experiences during their own undergraduate lives. When asked what motivated her to work in student affairs, Natalie said her involvement with “orientation programs” led to “some of the most formative experiences in [her] collegiate career.” Robert, a chief student affairs officer, recounted his transformative undergrad experience in greater depth:

I did not like my first year of college at [institution] . . . a small school. I was not a huge fan of campus life at the time, and I was just struggling with my transition. I had a director of residence life pull me aside during the spring semester and say, “Listen, I know you were involved in peer education in high school. Have you thought about applying for our peer education group here?” I had not considered it, but with that invitation, I took her advice. I applied for it and ended up being on the steering committee my sophomore year, and my student affairs experience just kind of blew up from there. So, it was really that conversation, that care, that she knew who I was, and that she understood, probably saw that I had not gotten involved yet, and made that outreach to me when she really didn’t have to. So, that moment kind of sparked me, because I think it really shaped a lot of who I was in college. I wanted to serve in that way for other college students.

Even those who had a negative interaction with student affairs were, in turn, drawn to the field. Melissa, who now serves as a dean, described the process of losing her leadership position as an RA:

[The] process of being held accountable for my mistakes and how the staff at my institution, my RD, and the upper administration walked me through that process with incredible love and care, but also that firm hand of justice was there, and that accountability—it radically transformed my own view on what it meant to be a person of integrity. My view on the balance of justice and grace and how they’re needed hand in hand . . . that was really the impetus after I graduated. I just said I want to be able to have the kind of impact on college students that they had on me.

In numerous stories like these, the implication was just as Melissa and Robert shared—because of the significance of their student experience, the professionals hoped to take part in offering transformative experiences to future students.

Third, several participants also shared that their motivation stemmed from a realization that their personal gifting aligned with the nature of the work. Thus, they viewed their work as a “calling” or as an avenue to “steward” their “giftings.” Rose, a vice president for student affairs, shared how her spiritual gifting aligned with her roles: “When I was [a residence director], I did a lot of shepherding. As a VP, I...