![]()

1

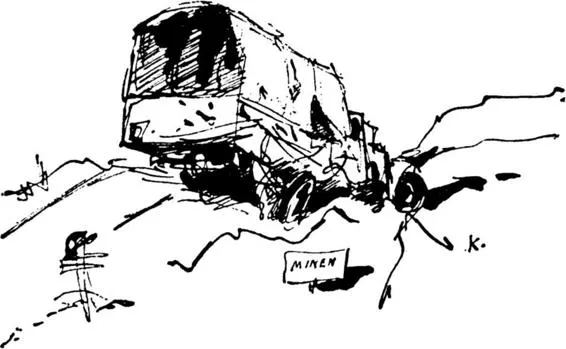

Six days after I had heard rumbling on the western skyline, that famous barrage that began it, I moved up from the rear to the front of the British attack. Through areas as full of organization as a city of ants—it happened that two days before I had been reading Maeterlinck’s descriptions of ant communities—I drove up the sign-posted tracks until, when I reached my own place in all this activity, I had seen the whole arrangement of the Army, almost too large to appreciate, as a body would look to a germ riding in its bloodstream. First the various headquarters of the higher formations, huge conglomerations of large and small vehicles facing in all directions, flags, signposts and numbers standing among their dust. On the main tracks, marked with crude replicas of a hat, a bottle, and a boat, cut out of petrol tins, lorries appeared like ships, plunging their bows into drifts of dust and rearing up suddenly over crests like waves. Their wheels were continually hidden in dustclouds: the ordinary sand being pulverized by so much traffic into a substance almost liquid, sticky to the touch, into which the feet of men walking sank to the knee. Every man had a white mask of dust in which, if he wore no goggles, his eyes showed like a clown’s eyes. Some did wear goggles, many more the celluloid eyeshields from their anti-gas equipments. Trucks and their loads became a uniform dust colour before they had travelled twenty yards: even with a handkerchief tied like a cowboy’s over nose and mouth, it was difficult to breathe.

The lorry I drove was a Ford two-tonner, a commercial lorry designed for roadwork, with an accelerator and springs far too sensitive for tracks like these. I was thrown, with my two passengers, helplessly against the sides and roof of the cab: the same was happening to our clothes and possessions in the back. The sun was climbing behind us. As far as we could see across the dunes to right and left stretched formations of vehicles and weapons of all kinds, three-ton and heavier supply lorries of the R.A.S.C., Field workshops with huge recovery vehicles and winches, twenty-five-pounders and quads, Bofors guns in pits with their crews lying beside them, petrol fires everywhere, on which the crews of all were brewing up tea and tinned meat in petrol tins.

We looked very carefully at all these, not having any clear idea where we should find the regiment. We did not yet know whether they were resting or actually in action. I realized that in spite of having been in the R.A.C. for two years, I had very little idea what to expect. I like to picture coming events to myself, perhaps through having been much alone, and to rehearse them mentally. I could not remember any picture or account which gave me a clear idea of tanks in action. In training we had been employed in executing drill movements in obedience to flag signals from troop leaders. We had been trained to fire guns on the move, and to adopt a vastly extended and exactly circular formation at night. But most of my training had been by lectures without illustrations: what few words of reminiscence I had heard from those who returned from actions in France and the desert, suggested that no notice of the manoeuvres we had been taught was ever taken in the field—which left me none the wiser. None of us had ever thought much of the drill movements and flag-signals. News films—just as later on that mediocre film ‘Desert Victory’—gave no idea where most of their ‘action’ pictures were taken. Even my own regiment had been known to put their tanks through various evolutions for cameramen.

So feeling a little like the simple soul issuing from the hand of God, animula blandula vagula, I gazed on all the wonders of this landscape, looking among all the signs for the stencilled animal and number denoting my own regiment. I was not sure yet whether this was an abortive expedition—tomorrow might find me, with a movement order forged on my own typewriter, scorching down the road to Palestine. All my arrangements had been made to suit the two contingencies. I had dressed in a clean khaki shirt and shorts, pressed and starched a week or two before in an Alexandria laundry. My batman

Lockett, an ex-hunt servant with a horseman’s interest in turn-out and good leather, had polished the chin-strap and the brasses of my cap and belt till the brasses shone like suns and the chinstrap like a piece of glass laid on velvet. In the lorry, besides Lockett, rode a fitter from Divisional Headquarters, who was to drive it back there if Lockett and I stayed with the regiment.

The guns, such desultory firing as there was, sounded more clearly: the different noise of bombs was distinguishable now. The formations on either side were of a more combatant kind, infantry resting, heavy artillery and the usual light anti-aircraft. A few staff and liaison officers in jeeps and staff cars still passed, the jeeps often identifiable only by their passengers’ heads showing out of enveloping dustclouds: but the traffic was now mostly supply vehicles moving between the combatant units and their ‘B’ or supply echelons.

Fifteen miles from our starting point and about four miles in rear of the regiment, I found our ‘B’ echelon, in charge of two officers whom I had known fairly well during my few months with the regiment, Mac—an ex-N.C.O. of the Scots Greys, now a captain; and Owen, a major; an efficient person with deceptive, adolescent manners, whom no one would suspect of being an old Etonian. It is difficult to imagine Owen at any public school at all: if you look at him he seems to have sprung, miraculously enlarged, but otherwise unaltered, from an inky bench in a private preparatory school. He looks as if he had white rats in his pockets. On these two I had to test my story.

I was afraid the idea of my running back to the regiment would seem absurd to them, so I began non-committally by greeting them and asking where the regiment was. ‘A few miles up the road,’ said Mac. ‘They’re out of action at the moment but they’re expecting to go in again any time. Have you come back to us?’ I said that depended on the Colonel. ‘Oh, he’ll be glad to see you,’ said Mac. ‘I don’t think ‘A’ Squadron’s got many officers left: they had a bad day the other day; I lost all my vehicles in BI the same night—petrol lorry got hit and lit up the whole scene and they just plastered us with everything they had.’ In spite of this ominous news, I was encouraged by Mac’s saying I was needed, and pushed on up the track until we came to the regiment.

Tanks and trucks were jumbled close together, with most of the men busy doing maintenance on them. A tall Ordnance officer whom I had never seen directed me to the same fifteen-hundredweight truck which had been the Orderly Room in the Training Area at Wadi Natrun. I left my lorry and walked, feeling more and more apprehensive as I approached this final interview. I looked about among the men as I went, but saw only one or two familiar faces; a regiment’s personnel alters surprisingly, even in eight months.

I looked about for Edward, my Squadron leader, and for Tom and Raoul, who had been troop leaders with me, but could not see them. The Colonel, beautifully dressed and with his habitual indolence of hand, returned my salute from inside the fifteen-hundredweight, where he was sitting with Graham, the Adjutant, a handsome, red-haired, amiable young Etonian. I said to Piccadilly Jim (the Colonel), ‘Good evening, sir, I’ve escaped from Division for the moment, so I wondered if I’d be any use to you up here.’ ‘Well, Keith,’ stroking his moustache and looking like a contented ginger cat, ‘we’re most glad to see you—er—as always. All the officers in ‘A’ Squadron, except Andrew, are casualties, so I’m sure he’ll welcome you with open arms. We’re probably going in early tomorrow morning, so you’d better go and get him to fix you up with a troop now.’ After a few more politenesses, I went to find Andrew, and my kit. The tremendous question was decided, and in a disconcertingly abrupt and definite way, after eight months of abortive efforts to rejoin. Palestine was a long way off and a few miles to the west, where the sounds of gunfire had intensified, lay the German armies.

![]()

2

I found Andrew, sitting on a petrol tin beside his tanks: I had met him before but when he looked up at my approach he did not recognize me. He was not young, and although at the moment an acting Major about to go into action in a tank for the first time in his life, Andrew had already seen service in Abyssinia in command of the native mercenaries who had been persuaded to fight for Haile Selassie. From Abyssinia he had come to Cairo and fallen, through that British military process which penalizes anyone who changes his job, from Colonel to Major. Later, he had gravitated to base depot, and being unemployed, returned to his war-substantive rank of Captain. As a captain he had come back to the regiment; it is not difficult to picture the state of mind of a man who knows he has worked well and receives no reward except to be demoted two grades. He now found himself second in command of a squadron whose squadron leader had been a subaltern under him before. What happened after that was probably inevitable. Andrew’s health and temper were none the better for the evil climate and conditions of his late campaign. Someone who knew him before—which I did not—said that he went away a charming and entertaining young man, and returned a hardened and embittered soldier.

He was a small man with blond hair turning grey, sitting on a petrol tin and marking the cellophane of his map case with a chinagraph pencil. His face was brick-red with sun and wind, the skin cracking on his lips and nose. He wore a grey Indian Army flannel shirt, a pair of old corduroy trousers, and sandals. Round his mahogany-coloured neck a blue silk handkerchief was twisted and tied like a stock, and on his head was a beret. Like most ex-cavalrymen he had no idea how to wear it. To him I reported, resplendent—if a little dusty—in dusty polished cap and belt.

He allotted me two tanks, as a troop, there not being enough on the squadron strength to make sub-units of more than two tanks. I drove my lorry with the kit on it to one of the tanks and began to unload and sort out my belongings. Lockett and I laid them out, together with the three bags of emergency rations belonging to the lorry. The Corporal, lately commander of this tank, departed, staggering under his own possessions barely confined by his groundsheet in an amorphous bundle.

Lockett was to go for the duration of the battle to the technical stores lorry where he had a friend and where he could make himself useful. To him I handed over the greater part of my belongings—the style in which I had travelled at Divisional Headquarters being now outmoded. I kept a half-share of the three bags of rations, which I distributed between my two tanks (this amounting to several tins of bully beef, of course, one or two of First American white potatoes, and some greater treasures, tins of American bacon rashers, and of fruit and condensed milk. A pair of clean socks were filled, one with tea, the other with sugar). I changed my peaked cap for a beret, and retained a small cricket bag with shirts, slacks, washing and shaving kit, writing paper, a camera and a Penguin Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Rolled up in my valise and bedding were a suit of battledress, my revolver, and a British warm. In my pocket I had a small flask of whisky, and in the locker on the side of the tank, in addition to the rations, I put some tins of N.A.A.F.I. coffee and Oxo cubes, bought in Alexandria. I now felt the satisfaction of anyone beginning an expedition—or as Barbet Hasard might have said on this occasion, a Voyage—in contemplating my assembled stores, and in bestowing them. As soon as this was finished I began to make the acquaintance of my tank crews.

My own tank was a Mk. Ill Crusader—then comparatively new to us all. I had once been inside the Mk. II, which had a two-pounder gun and a four-man crew, and was now superseded by this tank with a six-pounder gun and only three men in the crew, the place of the fourth being occupied by the breech mechanism of the six-pounder. This tank is the best looking medium tank I ever saw, whatever its shortcomings of performance. It is low-built, which in desert warfare, and indeed all tank warfare, is a first consideration. This gives it, together with its lines and its suspension on five great wheels a side, the appearance almost of a speedboat. To see these tanks crossing country at speed was a thrill which seemed inexhaustible—many times it encouraged us, and we were very proud of our Crusaders; though we often had cause to curse them.

From underneath this particular tank a pair of boots protruded. As I looked at them, my mind being still by a matter of two days untrained to it, the inevitable association of ideas did not take place. The whole man emerged, muttering in a Glaswegian monotone. He was a small man with a seemingly disgruntled youngster’s face, called Mudie. I found him, during the weeks I spent with him to be lazy, permanently discontented, and a most amusing talker. In battle he did not have much opportunity for talking and was silent even during rests and meals; but at all other times he would wake up talking, as birds do, at the first gleam of light and long before dawn, and he would still be talking in the invariable monotone long after dark. He was the driver of the tank.

The gunner was another reservist. His name was Evan, and he looked a very much harder case than Mudie, though I think there was not much to choose between them. Evan scarcely spoke at all, and if drawn into conversation would usually reveal (if he were talking to an officer) a number of injustices under which he was suffering at the moment, introducing them with a calculated air of weariness and ‘it doesn’t matter now,’ as though he had been so worn down by the callousness of his superiors as to entertain little hope of redress. In conversation with his fellows (I say fellows because he had no friends), he affected a peculiar kind of snarling wit, and he never did anything that was not directly for his own profit. Mudie would often do favours for other people. Evan would prefer an officer and then only if he could not well avoid it. Yet he was unexpectedly quick and efficient on two occasions which I shall describe.

We were at an hour’s notice to move. This meant, not that we should move in an hour’s time, but that, if we did move, we should have an hour in which to prepare for it. When I had sorted out my belongings, and eaten some meat and vegetable stew and tinned fruit, washed down with coffee, I lay down on my bedding with a magazine which someone had left on the tank, and glancing only vaguely at the pages, thought over the changes of the last few days, and confronted myself with the future. Desultory thumps sounded in the distance, occasionally large bushes of dust sprang up on the skyline, or a plane droned across, very high up in the blue air. Men passed and repassed, shouted to each other, laughed, sang, and whistled dance tunes, as they always did. Metallic clangs and the hum of light and heavy engines at various pitches sounded at a distance. Occasionally a machine-gun would sputter for a few seconds, as it was tested or cleared. The whole conglomeration of sounds, mixing in the heat of declining afternoon, would have put me to sleep, but for my own excitement and apprehensions, and the indefatigable flies.

But though I reflected, a little uncomfortably, on what might be happening to me in a few hours, I was not dissatisfied. I still felt the exhilaration of cutting myself free from the whole net of inefficiency and departmental bullshit that had seemed to have me quite caught up in Divisional Headquarters. I had exchanged a vague and general existence for a simple and particular (and perhaps short) one. Best of all, I had never realized how ashamed of myself I had been, in my safe job at Division until with my departure this feeling was suddenly gone. I had that feeling of almost unstable lightness which is felt physically immediately after putting down a heavy weight. All my difficult mental enquiries and arguments about the future were shelved, perhaps permanently. I got out my writing paper and wrote two letters, one to my mother and one to David Hicks in Cairo. Although in writing these letters (which, of course, got lost and were never posted) I felt very dramatic, the tone of them was not particularly theatrical. To my mother I wrote that I rejoiced to have escaped at last from Division and to be back with the regiment. I might not have time to write for a week or two, I added. To Hicks I sent a poem which I had written during my last two days at Division on an idea which I had had since a month before the offensive. I asked him to see that it got home as I had not got a stamp or an airgraph. He could print it in his magazine on the way, if he liked.

I had asked Andrew one or two questions in the hope of not showing myself too ignorant in my first action. But it was fairly plain that he knew nothing himself. ‘I shouldn’t worry, old boy,’ was all he would say. ‘The squadron and troop leaders don’t use maps much, and there are no codes at all, just talk as you like over the air—except for giving map-references of course—but you won’t need them. You’ll find it’s quite simple.’ When I had written my letters I got into the turret with Evan and tried to learn its geography. My place as tank commander was on the right of the six-pounder. I had a seat, from which I could look out through a periscope. This afforded a very small view, and in action all tank commanders stand on the floor of their turrets so that their eyes are clear of the top, or actually sit in the manhole on top of their turret with their legs dangling inside. Behind the breech of the six-pounder is a metal shield to protect the crew against the recoil of the gun, which leaps back about a foot when it is fired. On my side of the six-pounder was a rack for a box of machine-gun ammunition, the belt of which had to run over the six-pounder and into the machine-gun mounted the other side of it. There were also two smoke dischargers to be operated by me. Stacked round the sides of the turret were the six-pounder shells, nose downwards, hand-grenades, smoke grenades and machine-gun ammunition. At the back of the turret on a shelf stood the wireless set, with its control box for switching from the A set to internal communication between the tank crew, and on top of the wireless set a pair of binoculars, wireless spare parts and tommy-gun magazines. There was a tommy-gun in a clip on Evan’s side of the turret. On the shelf, when we were in action, we usually kept also some Penguin books, chocolate or boiled sweets if we could get them, a tin of processed cheese, a knife an...

![Alamein to Zem Zem [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3018615/9781786257512_300_450.webp)